'An Economic System that Destroys the Environment Destroys Itself'

René Passet, a development economist, has devoted himself to relationships between economics and the living world, drawing decisive lessons for his discipline from studying the environment. Committed from the point of view of ideas and in the field, René Passet in his latest book attacks the "predatory" globalisation that reduces the world to a market at the expense of the balance of nature and human needs. Eloge du mondialisme par un "anti" présumé (In praise of globalisation by an alleged "anti") is an offensive, lucid, documented essay of an intellectual honesty that is the mark of the true scientific mind. The citizen researcher holds up the model of sustainable development that respects human beings and the nature that supports them against the dominant neo-liberal model.

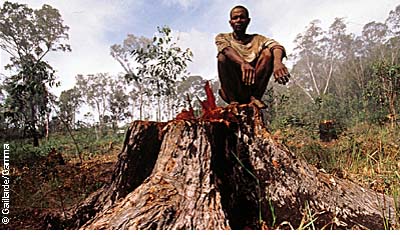

The best way to fight the over-exploitation

of resources is to remedy under-development.

Label France: Is environmental damage an accident of the neo-liberal economic system that can be corrected or a consequence of its actual essence? René Passet: I think, and there are many of us who think this, that harming the environment is part of the very nature of the system of free-trade and productivity since its main aim is to maximise profit, something which leads to the production costs being thrust back on to the environment. This trend is growing stronger today due to the fact that, as everyone knows, power has shifted from the public and political sphere to that of international finance and private interests, which increasingly drives the management and decision-making processes in businesses. The race for productivity and the over-exploitation of resources are linked to the need for fast profitability as regards financial assets. The economy regards pollution as an accident that can be sorted out by the very nature of the system itself, that is, in the best case scenario, by including the environmental costs in the price of products on the market. The latter thus remains the supreme regulator of the pollution that is reduced to a minor dysfunctioning, which we have to try and correct with a pricing scheme. There are several objections to this. Firstly, the sources of pollution are not always identified, neither are the victims and the damage, which means that the real costs are seldom considered. Then, and above all, the costs go beyond money. There are human lives at stake, non-renewable resources and irreversible effects on the natural environment in which each species, both prey and predator, fulfils a regulatory role and is interdependent with all the rest. This does not appear on the market that accords value to a natural asset only when it becomes rare, that is, when it is too late from the point of view of safeguarding the great natural balances. “The economy must be subordinate to human and environmental ends” Yet our role consists in keeping the environment that supports life, and human life in particular, as well as economic activities in working order. Because if you destroy the environment, you destroy everything, including the economy. LF: What place and role do you think the economy should have? R. P.: There is no economic theory, even among those we are combating at Attac, which would go as far as claiming that the economy is anything other than an activity confronting nature that is entirely given over to satisfying human needs. The economy does not have any other raison d’être. Today’s environmental, human and social problems arise from the fact that economic activity has become an end in itself instead of being a means benefiting human purposes. LF: Could you specify the difference between the notion of economic growth, which is the explicit aim of most societies, and the notion of sustainable development? R.P.: This is actually very important. The notion of growth is based on the following idea: the greater the national product, the better individual needs are satisfied. This view of the economy corresponds to the era in which its theory was established, that is, at the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century in Europe, when the basic needs of individuals were barely met. At this stage of economic development, it is true that the more you produce, the more well-being you create, as today in the poorest countries. The question of nature was shrugged off by the economists, since the activity was not yet irreversibly altering the biosphere, and it was not challenging its major functions, as is the case today with controlling the heat levels of our planet, for example. We can no longer think like that. However, the modern schools of economics persist in isolating the economic sphere from the human and environmental spheres. They think within the framework of an economy cut off from its context, unidimensional and which only takes account of the quantitative. Can it actually be stated today that double the number of cars on the Earth will double the well-being? When you see that in order to make growth happen, you destroy the environment, you can no longer separate off the economics, you have to replace it in the human context, notably in the area of values, so more cars, but for whom and what for? With what consequences? An economy linked to other spheres, that’s sustainable development, something which brings with it the question of the human and social issues and of nature. Growth that is obtained by destroying human beings and the natural environment is not development. We have to devise a new approach to the economy capable of thinking out the interdependencies of a complex world such as ours. When we adopt only material and financial criteria, we arrive at human and social aberrations. A rationality also exists based on the human end of economics. For example, on the cereals market you have two quintals of wheat produced by two different countries, and if you see only the volume, if the quality is the same, a quintal of wheat is a quintal of wheat and the best wins. It is the best market that is the best and, every time, this is the market of the most industrialised countries where farming is extremely mechanised and takes place at very competitive cost prices. For a wealthy country, the only implication of selling or failing to sell will be a slight rise or fall in its export income. But for a poor country, this wheat produced by dint of hard work under difficult conditions represents the only income of the people and countries that live on it. This cultivation of food crops is not competitive, but it is vital for societies where life itself is at stake. Other criteria therefore need to be asserted. If goods alone are considered, the rule to be applied is the equal treatment rule currently in force. But if we are interested in the condition of people and in the future of societies, it is entirely legitimate to uphold the opposite principle of unequal treatment for the benefit of the most disadvantaged. At a time when the WTO is trying to promote the most favoured nation clause and the equal treatment of national and foreign companies, I shall go even further by asserting that any country (including developed countries) should be entitled to meet its basic needs (notably for food) and to protect its vital sectors of activity from commercial competition (education, health and culture).

“The interplay of established interests is one of the main constraints on change”

Support for food crop farming should be an international priority, given what is at stake for the permanence of populations and rural environments, for development and for independence. It is now in the process of being wiped out by mechanised farming, which uses copious amounts of fertiliser, pesticides and herbicides in the hands of the developed countries.

There should be a real revolution in attitudes in order to change this situation. What do you think are the greatest constraints? These constraints are firstly attitudes. Nothing is harder to change than a system of thought that has to be stable, to withstand uncertainties, but which is also capable of change. We are too resistant, particularly in the field of economic theories. Neo-liberal theory presents itself as "the" scientific theory. Now the scientific field is, by definition, the field of the refutable. Those who claim that their theories are irrefutable so place them beyond the field of science, on the side of dogma, beliefs and opinions. Another imposture of this theory is the one which states that the market is neutral and must therefore be the single arbiter of economic decisions. This alleged neutrality of market control amounts, in reality, to condoning the system as it is with its unacceptable human and environmental costs, its relationships of power that always benefit the same people, those who have money and who attract it by virtue of the good old principle that you only lend to the rich. The other major curb on any change is, of course, the interplay of established oil and industrial interests that become the interests of certain governments prepared to compromise the future of the planet rather than affect the standard of living of those who elect them. This is absurd, because in doing this, they destroy us and themselves in the end.

When there are still so many problems to be resolved (like the problem of hunger throughout the world), protecting the environment is presented by some as a luxury.

Actually, in situations of poverty and unemployment, if a polluting company provides jobs and enables people to live a decent life, the ecological problem becomes secondary. And this is understandable. But the problem of combating poverty and of safeguarding the environment are nevertheless closely linked. Some people think that Western efforts to impose certain limits to pollution today on every country in the world penalise the industrialisation of the developing countries. How can we encourage them to take off while avoiding making the planet’s environmental problems worse? Of all the countries in the world, it is the poorest that are generally the least pollutant. Under-development, however, may also be harmful to nature, when it is the single source of wealth (wood, raw materials, animal species, natural landscape, etc.). By remedying under-development you remedy certain forms of overexploitation of natural environments and you provide ways of fighting for the preservation of the environment by increasing the national product. In addition, as the environment of the developing countries is relatively unpolluted, industrial development is possible before the environment is seriously threatened. So much so that the developing countries could benefit from the experience acquired by the developed countries in clean technologies, which are not always very costly and which mean that goods can be recycled and resources and energy saved. In order to do this, aid from the developed countries and the world institutions, the IMF and the World Bank would, of course, have to be increased. Even so it should be remembered that state aid from the OECD member countries is 0.22% of the GDP today, as against the 0.77% promised. Are you in favour of developing countries not being subject to the same strict standards as the countries already industrialised? Of course, because if we pollute less than the developing countries per unit of national product, as we produce infinitely more, we are on the whole the greatest polluters. Selling licences to pollute comes back to giving the richest, who no longer need to secure their basic development, the right to sully nature. It’s unacceptable. Where should we begin in order to reform the present system along the lines of sustainable development that has respect for what you call the "needs of the living world", the human, social and environmental needs? Standards ensuring the reproduction of the environment and society already exist. They are defined by agreements such as those of the International Labour Organisation (ILO), for example. Many basic environmental and social standards have been accepted as part of the negotiations. Let us remember that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, on which the United Nations Organisation is based, asserts the supremacy of fundamental rights (civil, political and social) over any other treaty. For the economic system in general, as well as for the major international trade organisations and agreements, this would already mean complying with these standards and ensuring that they are complied with. It would then be time to refine and complete them. On the other hand, I believe that rather than setting up new authorities, it would be better for those that already exist to fulfil their mission. Thus the WTO, instead of being the institution that systematically makes free trade prevail over every other criterion and other forms of international agreement, should guarantee compliance with environmental and social standards and with fundamental rights. In your view, compliance with these standards is not incompatible with an efficient economic sy stem? No. First of all, we should revise the notion of economic performance not just by the yardstick of money and capital growth, but by the yardstick of meeting human need. What is efficiency if not the degree of progress towards the fulfilment of an aim that we have set ourselves? Is it more important to run faster than others if it is in the opposite direction to the competition? We can imagine the enormous cost of converting our economies. How do we fund it? First of all it should be said that the technologies that preserve the environment do not waste energy and that they generate new activities and new goods, notably through the recycling of waste. “The multiple costs of damaging the environment are not made apparent” But above all, the real costs of the present system, both direct and indirect, over the short and the long term, are not made apparent, whether they are due to the normal operation of the system or to its "accidents", the repercussions of which are immense (health expenditure, unemployment costs, lower productivity or activity, aid, cleaning up of pollution, the destruction of the environment), not to mention loss of human life, which is beyond price. If these costs were included, it would be seen that by accepting sacrifices for the time being, we would ensure not just the permanence of the environment, but also minimisation of the system’s costs. If we wait until the problems become serious before trying to solve them, this will cost a great deal more. This commercial logic, based on productivity, results in reducing the range of plant and animal species involved, thus threatening biodiversity. How serious is this phenomenon? Here we once again encounter the notion of the short and the long term. Farming aiming at productivity actually results in growing only the species with the highest returns in terms of yield and resistance to this or that aspect of the environment. And the other varieties are de facto eliminated. This approach also favours production methods that are the most profitable in the short term. The problem with single crop production is that when you reduce the specific (the number of species) or even intra-specific (diversity within the same species) variety, you weaken the ecosystem. Depending on their age, species are not affected by the same diseases. Moreover, viruses affect some species and not others. If you maintain diversity of species and age, in the event of disease some will disappear but others will be resistant and the ecosystem will not be threatened. Whereas if you have just one species, you will lose everything in one fell swoop. Diversity is therefore an element of stability for the ecosystem and of security for human beings.

We also know that we have not discovered all the properties, notably the medicinal ones, of plants. When a species therefore disappears because its ecosystem has been destroyed, we lose the means of defending ourselves in the future against new diseases. We are indeed only familiar with a tiny minority of the species living on Earth, and we are in the process of destroying this natural heritage without knowing what we are destroying. It’s a disaster. What should be the legal basis of environmental rights, that is, of the right of life on Earth to be preserved in order to be able to pursue and sanction polluters? On the notion of responsibility towards future generations? The Napoleonic law, from which we have inherited in France in particular, is a law that governs men’s relationships with things and with each other. It does not therefore have it in its power to govern interdependencies that evaporate in time and space and that constitute par excellence the area of environmental protection. The greenhouse effect, damage to the ozone layer and pollution of the sea elude the traditional framework of the law. In these instances, it is very difficult to identify the perpetrator or various perpetrators of pollution. The victims themselves are not easily identified, nor is the pollution that attacks them either. All this still holds good in the case of oil slicks, acid rain or radioactive clouds that ignore national boundaries. The consideration of nature is based on a very long-term view; against this, the very long term course of the economy is trivial. Planning fifty years ahead on an economic scale is already significant and yet with regard to the rhythm of nature, the renewal of a natural resource and damage to the environment, it is nothing. It is centuries, millennia, that are at issue. We then touch on the issue of ethical responsibility. We have reached the time when the economy can no longer bypass the issue of values. Why should we deprive ourselves today for future generations whom we shall not even know? There is no answer to this question in economic terms. It is something else that appears, what the philosopher Hans Jonas calls the "responsibility principle", that is, our responsibility towards life and the development of humanity. Here we are entering the field of values in which, by definition, there is no pre-established response. The economy is only the instrument, it is values that give meaning to life. As these values are many and undemonstrable, this implies two things: the superiority of the political sphere (which affects ends) over the economic function, and the legitimacy of democracy, which allows values to be debated and to coexist. Giving primacy to the human purpose involves not tolerating anything (destitution, oppression) that hinders the human being’s ascent towards himself. Humanity is in a state of perpetual growth. Here is a vision that I think can be offered to everyone. If we know nothing about the aim of this adventure, we must at least allow human beings to pursue the discovery of their own nature in freedom.

From the standpoint of conventional economic thinking, what does the inclusion of environmental issues involve, notably for investment?

This is another of our objections to the present system, which wants to reduce everything to a collection of individual interests. Admittedly, they do exist, and every time the market is able to regulate without undermining the general interest, we are in agreement. But not everything can be reduced to that. And the environment in particular comes under the general interest and should not just be left in the hands of private and commercial interests. The profitability of certain investments, such as infrastructures (bridges, dams, railway lines) is not immediate since they involve promoting trade and the development of activities in general. Even when showing a loss, these companies could be very rational in view of their usefulness for the development of the entire community. This is why only the State and the nation can pay for this type of investment that is profitable over the long term and indirectly, their profits benefiting a multitude of those involved. The authorities include this constraint, which private enterprises cannot do because they are never able to think further than the next twelve to fifteen years. This is why the TGVs (high-speed trains) have not been developed anywhere else than in France, because it is a project planned over fifty years and one that is not immediately profitable. Now, in the United States, for example, there is no agency that would take on this role of long-range forecasting. The private sector cannot fulfil every function. Look at the catastrophic consequences of the privatisation of the railways in the United Kingdom, or those of energy distribution in California. It’s a short-term rationality.

What do you think is the most serious threat to life on Earth?

Among the greatest threats to the environment, the one that stands out is the problem of water and its distribution, which is very erratic throughout the world. This problem could really be deferred if we started to control water consumption today particularly given that there are economical methods of doing so. There is also, of course, global warming. But I believe that the worst threat is the race for productivity associated with the frenetic profitability of financial capital because it is at the heart of all the other problems. Interview by Anne Rapin By René Passet: • L’Economique et le Vivant, published by Payot, Paris, 1979. Work which was awarded a prize by the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences.

• L’Illusion néolibérale, published by Fayard, Paris, 2000.

• Eloge du mondialisme, published by Fayard, Paris, 2001.

• Our common future, report by Brundtland of the World Commission for the Environment and Development, United Nations, 1987 (available in French and English).