What Do Israelis Think About Americans? Start With Disdain.

Naomi Zeveloff

Jerusalem — Though Israel is a famously fractious society, Israelis tend to agree on one thing: Their strongest supporters are an inherently dupable people.

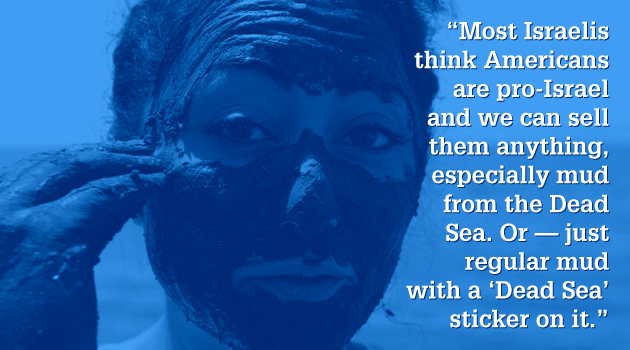

“Most Israelis think Americans are pro-Israel and we can sell them anything, especially mud from the Dead Sea,” said David Lifshitz, the lead writer for the Israeli comedy show “Eretz Nehederet,” or “Wonderful Land.”

“Or — just regular mud with a ‘Dead Sea’ sticker on it.”

But it’s not just American tourists whom many Israelis see as guileless. American foreign policy is held up to similar scrutiny here, even as Israel receives billions of dollars in foreign aid from the United States each year.

“Americans are perceived to be naive, especially when it comes to the Middle East,” said Uri Dromi, who served as a spokesman for the Yitzhak Rabin and Shimon Peres governments. “It is a bad neighborhood and it seems like they just don’t realize it.”

The naivete Israelis perceive in Americans is not just something they believe only Israel’s adversaries exploit; Israelis believe they can do so, too — and do. In a secretly recorded video of a 2001 discussion with a group of terror victims in the Ofra settlement in the Israeli occupied West Bank, now-Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu laid out this widely held perception.

“I know what America is,” Netanyahu, then on political hiatus after an election defeat, told the settlers when one asked whether his proposal for a “large scale” attack on the Palestinians would be met with global condemnation. “America is a thing that can be easily moved, moved in the right direction. They will not bother us… Let’s suppose they [the Bush administration] will say something. So they say it — so what? Eighty per cent of the Americans support us. It’s absurd! We have such [great] support there! And we say… what shall we do with this [support]?”

The paradox that Israelis rely on — and expect — American support and yet don’t trust American judgment on Middle Eastern affairs helps explain the recent U.S.-Israel dustup in Washington. On March 3, that clash reached its climax when Netanyahu appeared before a joint meeting of Congress to warn the assembled lawmakers against their own president’s negotiations, together with other countries, with Iran ahead of a possible deal on that country’s nuclear program.

Israelis were split on the value of Netanyahu’s trip to Washington, which was widely seen as a play to the prime minister’s right-wing base before the March 17 election. But most Israelis were in agreement about their premier’s message. About three-quarters of Israelis “don’t trust Obama to be a reliable ally and to deal effectively with the Iranian nuclear threat” said Eytan Gilboa, a senior researcher at the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies.

That opinion was evident on the Israeli street the day of Netanyahu’s speech to Congress, despite all the administration’s measures on behalf of Israel’s security that Netanyahu took pains to laud.

“Obama is very hostile against Israel,” said Effi Hasut, a 50-year-old hairdresser who was smoking on the patio outside his salon in downtown Jerusalem. “He tried to please the Arab world at our expense. He doesn’t understand them.”

Part of the reason Israelis think Americans just don’t get the Middle East, said Alex Mintz, a political psychologist at IDC Herzliya, is that they consider themselves close front-row observers of American foreign policy in the region. And they have watched the Middle East grow more violent and unstable in recent years, he said.

Of course, Israelis themselves have been much more than just spectators in the region, with a massive impact of their own. But according to Mintz, whose new book, “The Polythink Syndrome,” deals with recent U.S. policy in the Middle East, Israelis are skeptical of American intentions — except when it comes to supporting them. “[Israelis] are appreciative of the strong and solid relationship, with the U.S. But they also caution against subsequent moves of the U.S. in the region because they don’t think those are successful or led to good outcomes,” he said.

Yet there’s another reason that Israelis don’t trust Americans, and that has to do with a wider, powerful strain of mistrust in Israeli society.

“Israelis grow up with the expression of ‘never be a freier,’ i.e., a push-over or loser, someone who can be taken for a ride,” Ari Ben Zeev wrote in his 2001 book “The Xenophobe’s Guide to the Israelis.” “This omnipresent need ‘not to be a freier’ can be traced to 2,000 years of being a struggling minority and also to the Middle Eastern neighborhood rule that everything is negotiable.”

Some Israelis think of American tourists and American immigrants in particular as freiers. In a 1998 study of American Jewish immigrants to Israel, by Linda-Renee Bloch, one interviewee said he felt that Israelis saw him as having made the ultimate freier move by moving to Israel in the first place. In their eyes he fell for Israel’s “sales pitch” and traded the relative ease of American life for Israeli instability.

An American might respond with the saying “Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me,” and observe that this outlook, with deep roots in the American psyche, rebuts the Israeli stereotype of Americans as ever-trusting.

But for many Israelis, the question is, why trust anyone even once?

The fear of being taken advantage of manifests in myriad ways. Israelis have a reputation as hardcore bargainers, and they’re known to cheat on their taxes — both because they can and because they think they’re getting a bad deal from the government as it is.

On the political level, Israelis don’t trust their leaders to say what they mean, and they don’t trust their adversaries, either. “Israelis think Arabs are liars,” said Amnon Cavari, a political scientist with IDC Herzliya. “I don’t think that Arabs are liars, but a lot of Israelis think so. They say, ‘They never mean what they say.’”

This deeply held cynicism flies in the face of American statecraft, Dromi said. “There is something admirable in the American approach to the world. It is a sense of decency, and you expect your partners and your opponents to be fair,” he said. “If they tell you something, they must be telling you the truth; they are going to keep their word.”

Of course, that has not always been the American approach. President Ronald Reagan’s visceral distrust of the Russians led him to adopt the Russians’ own proverb “Trust, but verify” as the cornerstone of his negotiations with the Soviet Union. But with this principle in hand, he did, in fact, reach successful nuclear arms agreements with America’s foremost global adversary in talks with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev.

And of course, in the case of Iran, America acted covertly with Britain to oust that country’s troubled but democratically elected government and reinstall the Shah of Iran as ruler in 1953.

Still, many Israelis fundamentally disagree with what they take to be the American approach, especially when it comes to the Iranians. “Most Israelis will tell you they are bluffing and all they want to do is gain time, and then they are going to spit in our face,” said Dromi.

The fact that Israelis see their benefactor as overly credulous also breeds resentment in some corners of Israeli society. In recent years, some right-wing Israelis and their supporters have been increasingly vocal about the idea that Israeli self-determination is put at risk when America picks up the defense tab.

“I think, generally, we need to free ourselves from it,” Naftali Bennett, chair of the Jewish Home party, told The Jewish Press in 2013. “We have to do it responsibly since I’m not aware of all aspects of the budget. I don’t want to say, ‘Let’s just give it up,’ but our situation today is very different from what it was 20 or 30 years ago.”

According to Dromi, for most Israelis, there is in the end an understanding of their country’s current reality, for better or for worse: “If you wake an Israeli in the middle of the night and say, ‘Who is your best friend in the whole world?’ they will say the United States of America.”

In his March 3 speech, however, Netanyahu warned that Israel would “stand alone” if it had to. “We are no longer scattered among the nations, powerless to defend ourselves,” he told the U.S. lawmakers. “This is why, as prime minister of Israel, I can promise you one more thing: Even if Israel has to stand alone, Israel will stand.”

In many ways, this image of Israel as the Jewish bunker flies in the face of much of what the original Labor Zionists declared they were trying to achieve in reconstructing Jewish life in a nation-state — not just in terms of security, but also psychologically.

Yitzhak Rabin, perhaps the last classical Labor Zionist leader of Israel, sought to convince both his own people and the broader world that Jews had left behind the ghetto mentality that Labor Zionists felt infected Jewish consciousness in Europe over many centuries. “Israel,” he declared in his first speech to the Knesset on becoming prime minister in 1992, “is no longer a people that dwells alone.”

But back at the hair salon, Hasut was with Bennett.

“If I depend on your support, I should do what you tell me to,” he said. “The Israeli government doesn’t need the support that America gives them. Why do they take the money? Why can’t they just say: ‘We don’t need this money. Don’t tell us what to do. We are already a country for many years. We can be independent.’?”

Will Israel be able to fend for itself in such circumstances?

“Of course,” he said. “So maybe we won’t have F16s.”

Contact Naomi Zeveloff at zeveloff@forward.com or on Twitter @naomizeveloff