The Last Confederate Is Clarence Thomas

Charles Pierce, Esquire

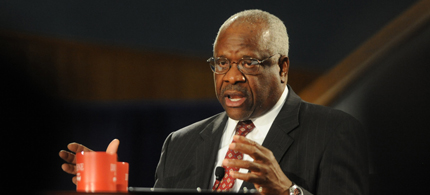

Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas. (photo: AP)

n Monday, the Supreme Court handed down its decision in the case of Town of Greece v. Galloway. In its 5-4 decision, the Court determined that the town could open its public meetings with a prayer. Writing for the majority, Justice Anthony Kennedy said the prayers did not violate the Establishment clause of the First Amendment because there is a long-standing tradition of such prayer, and because, in Kennedy's opinion, the prayers were not coercive in regards to the people at the meeting who might not share the religion in which the prayers are based. Justice Clarence Thomas voted with the majority. In his concurring opinion, however, he went much further.

n Monday, the Supreme Court handed down its decision in the case of Town of Greece v. Galloway. In its 5-4 decision, the Court determined that the town could open its public meetings with a prayer. Writing for the majority, Justice Anthony Kennedy said the prayers did not violate the Establishment clause of the First Amendment because there is a long-standing tradition of such prayer, and because, in Kennedy's opinion, the prayers were not coercive in regards to the people at the meeting who might not share the religion in which the prayers are based. Justice Clarence Thomas voted with the majority. In his concurring opinion, however, he went much further.

Thomas stated, flatly, that the Establishment clause never was meant to apply to the states (or to local governments) at all. In Thomas's stated view, the Establishment Clause "is best understood as a federalism provision - it protects state establishments from federal interference but does not protect any individual right." In short, Thomas is saying that the separation of church and state is meant to apply only to the federal government. This was such a radical re-interpretation of the existing law that not even Antonin Scalia was willing to go as far off the diving board as Thomas did. But it is of a piece with Thomas's general view of the relationship between the federal government and the states, and it is of a piece with the fact that Thomas has allied himself for his entire career on the bench with what has proven to be the most fundamentally dangerous constitutional heresy. That there is an obvious historical irony to this can't be lost on anyone. To see this more clearly, it's necessary to go back almost 20 years to another case, one on which Thomas was on the losing side, but one in which he stated most directly the philosophy that led him to write his dissent this week.

On May 25, 1993, in a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that, absent an amendment to the Constitution, the states could not limit the terms of their representatives in Congress. At issue was a term limits law that had been passed in Arkansas, term limits being a front-burner issue at the time thanks to the efforts of Newt Gingrich and his Contract With America. The majority decided that, because the Constitution was a pact between all the people of the United States, and not a compact between states, only the people themselves could change the process by which they elected their representatives to the Congress. Writing for the minority, Thomas disagreed, strongly.

Emphasizing that "the Federal Government's powers are limited and enumerated," Justice Thomas said that "the ultimate source of the Constitution's authority is the consent of the people of each individual state, not the consent of the undifferentiated people of the nation as a whole." Consequently, he said, the states retained the right to define the qualifications for membership in Congress beyond the age and residency requirements specified in the Constitution. Noting that the Constitution was "simply silent" on the question of the states' power to set eligibility requirements for membership in Congress, Justice Thomas said the power fell to the states by default. The Federal Government and the states "face different default rules," Justice Thomas said. "Where the Constitution is silent about the exercise of a particular power -- that is, where the Constitution does not speak either expressly or by necessary implication -- the Federal Government lacks that power and the states enjoy it."

That has been the basic argument since the Constitutional Convention began, and every time that it has been litigated -- in the debates over ratificaton of the Constitution, in the battle over the tariff with South Carolina, when Webster stood up to Hayne, when John C. Calhoun fashioned his doctrine of nullification out of it, when the nation tore out its own guts between 1860 and 1865, and, most recently, when "massive resistance" became the strategy through which white supremacy sought to break the civil rights movement -- it has failed. It was the basis for the Reconstruction amendments, especially the 14th, which Thomas curiously elides in both his term-limits dissent and his government-prayer concurrence.

Nonetheless, it persists, as we've seen most recently in the rhetoric of Tea Party politicians, and on the broken hills around the Bundy Ranch. It persists because there always are forces that seek power by denying the basic fact that of a United States of America, and that the reason for that is that the Constitution is an agreement between the citizens of that country, not between 50 independent republics. That is the reason for the first three words of the Constitution, and the basis for the American political commonwealth. In the nullification crises of the mid-1800's, President Andrew Jackson called James Madison himself out of retirement. Madison's work on the Virginia and Kentucky resolves of 1798 was being used to justify nullification, and Madison responded with a ringing endorsement of the view that the Constitution was a compact between all of the American people, and not an agreement between states. In a letter to Edward Everett that he knew would be circulated widely, Madison wrote:

It was formed, not by the Governments of the component States, as the Federal Govt. for which it was substituted was formed; nor was it formed by a majority of the people of the U. S. as a single community in the manner of a consolidated Government. It was formed by the States - that is by the people in each of the States, acting in their highest sovereign capacity; and formed, consequently by the same authority which formed the State Constitutions.Being thus derived from the same source as the Constitutions of the States, it has within each State, the same authority as the Constitution of the State; and is as much a Constitution, in the strict sense of the term, within its prescribed sphere, as the Constitutions of the States are within their respective spheres; but with this obvious & essential difference, that being a compact among the States in their highest sovereign capacity, and constituting the people thereof one people for certain purposes, it cannot be altered or annulled at the will of the States individually, as the Constitution of a State may be at its individual will.

That brings us back to Clarence Thomas. Long-distance psychoanalysis is almost always worthless, so I will leave that to the savants of the Beltway press corps. I only will point out that, in his career as a Supreme Court justice, Clarence Thomas, an African American from rural Georgia, presents us with a staggering political and historical contradiction. He is the last, and the truest, descendant of John C. Calhoun.