The Betrayal of Cecily McMillan

Marc Ash

(photo: Giles Clarke) New York Police arrest a demonstrator on day 7 of the Occupy Wall Street Demonstrations, 09/23/11.

rial by Jury – it’s a powerful thing. If the state accuses an individual of a crime, that individual in America is guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution a trial by a jury of peers. That guarantee ensures that the state cannot by caveat or in secrecy assign guilt to an individual of its own accord.

rial by Jury – it’s a powerful thing. If the state accuses an individual of a crime, that individual in America is guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution a trial by a jury of peers. That guarantee ensures that the state cannot by caveat or in secrecy assign guilt to an individual of its own accord.

But what if the state could by promulgating fear and manipulating process convince juries to carry out its will without question?

If Cecily McMillan can be convicted by twelve New Yorkers of assaulting a police officer, based on the evidence presented at her trial, then anyone can be convicted of anything, anywhere – regardless of the facts. Congratulations to the New American Security State. The jury itself is now an efficient tool of political oppression.

The prosecutor in McMillan had to prove not only that McMillan struck the officer, Grantley Bovell, but that she did so with intent to harm him (with malice). The case should never have gone to trial, and never would have gone to trial had it not been for the political nature of what McMillan was involved in. She and all Occupy demonstrators were targeted by the NYPD. There was a clear message: “You will not do this here … we will stop you.” It was personal, it was violent, and it showed no concern whatsoever for the constitutional rights of the protesters.

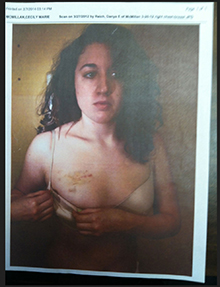

The burden of proof in a case like this is so high that under normal circumstances it never goes to trial. Bovell was significantly larger and stronger than McMillan and far more capable of doing bodily harm to her than she was to him. Unsurprisingly, her injuries were far more significant than his. She was literally covered in bruises, suffered a seizure, and ultimately required hospitalization.

Image showing the injury to Cecily McMillan’s breast. (image: Cecily McMillan/Occupy activists)

Defending such a case is normally so routine that no prosecutor wants to touch it. In fact the prosecutor offered McMillan a deal: plead guilty and avoid jail time. McMillan refused, stood on principle, and put her faith in American justice and a jury. That was a big mistake.

What Cecily McMillan did not know, and what her attorney Martin Stolar should have impressed upon her, is that American juries are quite susceptible to manipulation by the court. The court has significant power to shape the proceeding and steer the outcome. Ultimately the jury must do what it is instructed to do by the court. They did.

Normally when a jury of twelve finds a defendant guilty of a crime there is a presumption that they were moved by the evidence, but this case would take a strange twist.

Enter Juror Number Two. [And eight others.]

On May 6, 2014, only days after the conclusion of the trial, Charles Woodard, Juror #2, speaking on behalf of “9 of the 12 member jury,” wrote to Judge Ronald Zweibel pleading for leniency in sentencing for the woman they had just voted to convict. A woman then sitting in a prison cell at New York’s notorious Rikers Island detention center.

To the jurors’ credit this extraordinary act of civil engagement may very well have spared McMillan a much longer sentence. In the end the sentence handed down by Judge Zweibel was 3 months. Far less than the 7 years she could have faced.

The jurors in McMillan did however have another option, independence and conviction in their beliefs. In allowing themselves to become an instrument in a political prosecution, the jury abdicated its primary purpose.

The primary function of a jury is not to convict criminals or decide innocence or guilt, the jury’s most important function in a free society is to compel the government to prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt. They are all Catchers in the Rye, the last and most important safety mechanism in the American justice system.

For a police state to flourish, the police must have a reasonable expectation of impunity. That is to say that regardless of what they do in the line of duty, no jury will ever convict them of anything. The trial of Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) police officer Johannes Mehserle was a case study in how easily an American jury can be convinced to ignore evidence in pursuit of a ruling favorable to police.

Mehserle was on trial for shooting suspect Oscar Grant in the back of the head at point-blank range while Grant was handcuffed and lying face down on the ground. All captured on video and presented to the jury. Ultimately the jury found Mehserle guilty of involuntary manslaughter. He was sentenced to two years. With time off for good behavior and time served, he was free in less than eight months. Had the roles been reversed, a police officer handcuffed and executed by a suspect, that suspect would in all likelihood have been convicted of first degree murder, with special circumstances, received the death sentence, and even in California most likely executed.

On the streets of Oakland, California, a handfull of rubber bullets, 10/26/11. (photo: dinab/Flickr)

American juries simply do not question authority. As a result they do not exist. Instead they all too often function as a public relations instrument of the police state. Particularly in politically motivated trials.

It was great that the McMillan jurors threw her a life preserver. That would not however have been necessary had she not been thrown overboard to begin with.

Marc Ash was formerly the founder and Executive Director of Truthout, and is now founder and Editor of Reader Supported News.

Reader Supported News is the Publication of Origin for this work. Permission to republish is freely granted with credit and a link back to Reader Supported News.

http://readersupportednews.org/opinion2/277-75/24016-the-betrayal-of-cecily-mcmillan