Income Inequality is Not a Myth

Derek Thompson

Oct. 26, 2011

A new study from the Congressional Budget Office tells us what we all (should) already know: income inequality is real and the causes are terrifyingly inextricable.

Income inequality is a myth.

That was the takeaway from five economic studies collected by James Pethokoukis that found income gains were shared fairly equally in the 30 years before the Great Recession. What little income inequality existed, he claimed, was off-set by inflation. The stuff that the richest 10 percent like to buy has gotten more expensive than the stuff the poorest 10 percent like to buy. So, not only are low-income households making real money, but also their income is going further every year.

These studies are important contributions to the broader debate about the working class. But they represent a minority opinion. Almost everything we know about wages and prices tells us that the typical household has suffered a Lost Decade for market wages. Just as important, the price of necessities -- such as health care, a college education, a house, and energy to heat your home and run your car engine -- is growing faster than our incomes.

I'm going to try to tell this story in five parts: What's going on with wages; why we're dealing with a global crisis; and what government can and can't do.

WAGES

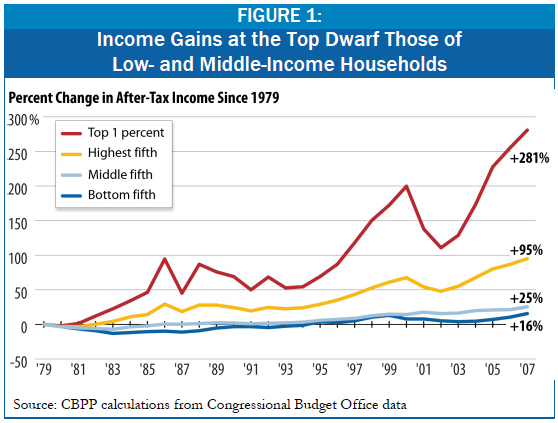

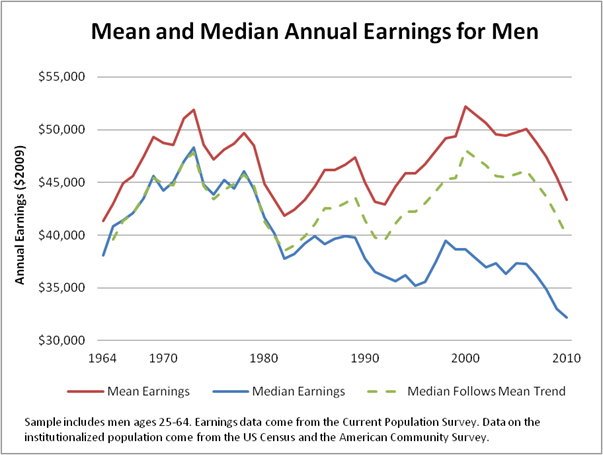

The Congressional Budget Office's monster analysis of income inequality is a useful entry in this debate. What it found matches the graph that leads this article, from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

The Congressional Budget Office's monster analysis of income inequality is a useful entry in this debate. What it found matches the graph that leads this article, from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

CBO found that in the three decades between 1979 and the beginning of the Great Recession, real household income grew 60 percent overall. But it didn't grow evenly.

Among the poorest fifth of households, income grew 18 percent. For the next three quintiles, it grew just shy of 40 percent. For the richest fifth, it grew 65 percent. And for the top percentile, it grew by a whopping 275 percent, which means it nearly tripled. Bottom line: Income inequality exists.

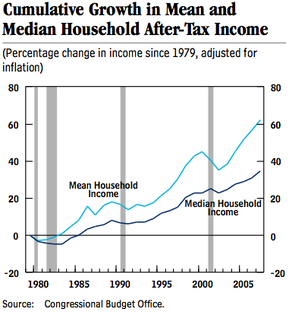

Let's focus on the median household: poorer than half the country and richer than the other half. There are two ways to look at median income growth. The first is "after-tax income," the first graph to the left. That's the money in your pocket after government taxes and benefits. This measure has grown by nearly 40 percent since 1979. That's not so bad.

Let's focus on the median household: poorer than half the country and richer than the other half. There are two ways to look at median income growth. The first is "after-tax income," the first graph to the left. That's the money in your pocket after government taxes and benefits. This measure has grown by nearly 40 percent since 1979. That's not so bad.

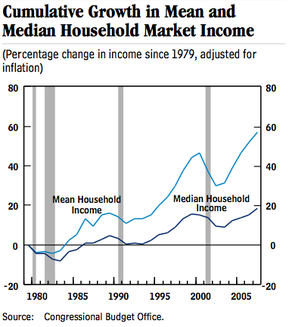

The second metric is market income, the second graph to the left. That's your workplace compensation, plus any money you made from a small company (public speaking, quilt-selling, etc) and investments. This measure didn't grow between 1980 and 1992, and it's basically flatlined since the mid-1990s. This graph looks like two lost decades framing a window of real income growth between 1991 and 1999. Bottom line: Median wages had a rough time in the 1980s and an equally rough time in the 2000s.

And ... here's the kicker ... then the recession happened. Ten million people lost their jobs between 2007 and 2011. The economy has teetered on the edge of deflation for two years. Wages basically stopped growing, and that's for the lucky 84 percent of the labor force that had full-time work.

WHAT IF THE 1950s WENT ON FOREVER?

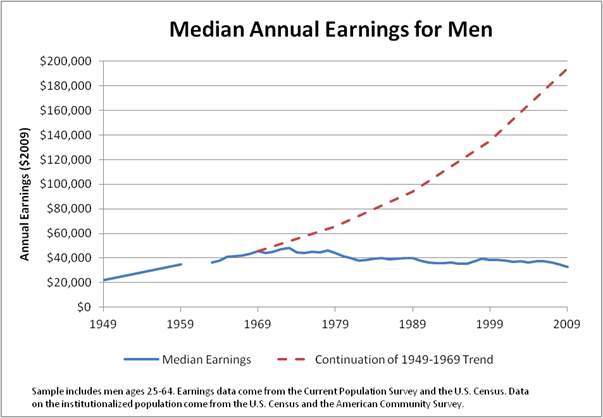

Income equality looks very real, and we can trace its explosion to the last 30 years. But what if the last 30 years didn't happen -- or rather, what if income gains from the 1950s and 1960s continued forever? How much more would the typical family make?

We posed the question to Michael Greenstone, the director of the Hamilton Project. Between 1950 and 1970, we saw fabulously high economic growth, he said. Earnings grew 44 percent per decade -- more than three times faster than they've grown over the last 30 years. If that trend had continued, Greenstone said, the median man would be earning a whopping $194,000 per year today!

That seems more than a little implausible, Greenstone admits (and we agree). A more plausible counterfactual is that median earnings kept up with average earnings, as they did prior to the 1970s. In this scenario the median man's earnings would be $41,875 instead of $33,000 -- $9,000, or 27 percent, higher.

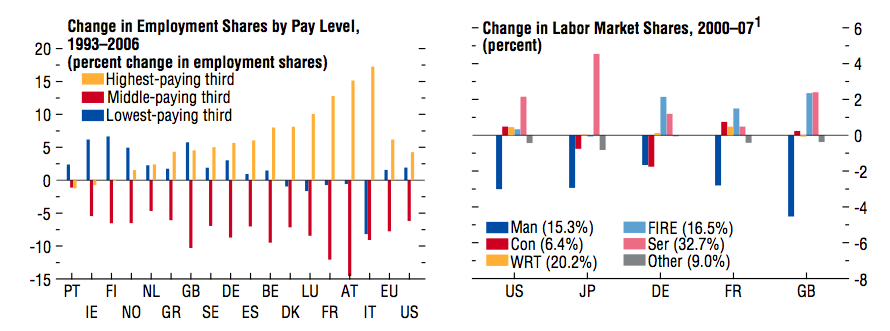

Nouriel Roubini boiled down the factors behind this worldwide growth of income inequality to four issues. I'll boil them down to two. Trade and technology.

Nouriel Roubini boiled down the factors behind this worldwide growth of income inequality to four issues. I'll boil them down to two. Trade and technology.

1. Technology. In the long run, tech tends to grow economies. In the short run, it can create a lot of carnage. (Definitely read this article: Why Workers Are Losing the War Against Machines). Machines can make most cars better than people. Computer programs can crunch data faster than people. If humans don't find skills that aren't more easily performed by non-human bots, they'll either go without work or have to work low-skill service jobs that haven't been automated yet.

2. Trade. "A basic principle of international trade theory is that greater trade with a labor-abundant economy will reduce the wages of workers in a capital-abundant economy," Roubini writes. That's why so many clothing manufacturing jobs have gone to China, and why even some Chinese jobs have gone on to still poorer countries, like Bangladesh and Vietnam. Cheap stuff is good for consumers, but not always good for workers in high-wage countries like the U.S.

But trade isn't just about making cheaper socks. The tradability of services threatens even white collar workers. With better information technology, more services are tradable and susceptible the same forces that sucked American manufacturing and IT jobs out of the U.S.

The U.S. doesn't have much of an industrial policy to direct funds away from manufacturing toward another industry that could accept these millions of displaced workers. Most of our "equality policy" is run through the tax code through the redistribution of income to poorer families. So how are we doing there?

ARE TAXES HELPING OR HURTING?

Let's come up for air and review. Income inequality exists. It's getting worse. And it's global. So what can government do? The simplest thing is to tax people who are benefiting the most from the market and redistribute some of that money in the form of income and services to the folks who are doing the worst.

What the CBO found in yesterday's report is that the federal income tax has become slightly more progressive. But the overall tax code -- which includes payroll taxes and excise taxes -- has not done much to dampen the impact of income inequality. In fact, the CBO found that the increase in inequality of after-tax income was greater than the increase in inequality of before-tax income. Another way of putting this is to say that the poorest 20 fifth of households saw their share of total transfer payments fall from 54 percent in 1979 to 36 percent in 2007. Over that time, transfer payments as a share of market income did not change.

This makes it sound like government is ganging up with capitalism on the middle class. That's not exactly the case, either. The lowest quintile's share of all federal taxes has fallen over the last 30 years. The top quintile is paying more. The top percent is paying about the same share as it did in 1982. Here's the picture:

.png)