6 RIDICULOUS LIES YOU BELIEVE ABOUT THE FOUNDING OF AMERICA

Jack OBrien, Elford Alley

When it comes to the birth of America, most of us are working from a stew of elementary school history lessons, Westerns and vague Thanksgiving mythology. And while it’s not surprising those sources might biff a couple details, what’s shocking is how much less interesting the version we learned was. It turns out our teachers, Hollywood and whoever we got our Thanksgiving mythology from (Big Turkey?) all made America’s origin story far more boring than it actually was for some very disturbing reasons. For instance …

(SCROLL DOWN)

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

#6. The Indians Weren’t Defeated by White Settlers

The Myth:

Our history books don’t really go into a ton of detail about how the Indians became an endangered species. Some warring, some smallpox blankets and … death by broken heart?

When American Indians show up in movies made by conscientious white people like Oliver Stone, they usually lament having their land taken from them. The implication is that Native Americans died off like a species of tree-burrowing owl that couldn’t hack it once their natural habitat was paved over.

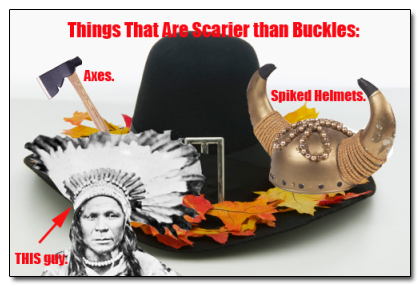

But if we had to put the whole Cowboys and Indians battle in a Hollywood log line, we’d say the Indians put up a good fight, but were no match for the white man’s superior technology. As surely as scissors cuts paper and rock smashes scissors, gun beats arrow. That’s just how it works.

This is all the American history you’ll ever need to know.

The Truth:

There’s a pretty important detail our movies and textbooks left out of the handoff from Native Americans to white European settlers: It begins in the immediate aftermath of a full-blown apocalypse. In the decades between Columbus’ discovery of America and the Mayflower landing at Plymouth Rock, the most devastating plague in human history raced up the East Coast of America. Just two years before the pilgrims started the tape recorder on New England’s written history, the plague wiped out about 96 percent of the Indians in Massachusetts.

In the years before the plague turned America into The Stand, a sailor named Giovanni da Verrazzano sailed up the East Coast and described it as “densely populated” and so “smoky with Indian bonfires” that you could smell them burning hundreds of miles out at sea. Using your history books to understand what America was like in the 100 years after Columbus landed there is like trying to understand what modern day Manhattan is like based on the post-apocalyptic scenes from I Am Legend.

“They call it ‘The city that never sleeps’ because the only guy who lives there is a notoriously sarcastic rapper.”

Historians estimate that before the plague, America’s population was anywhere between 20 and 100 million (Europe’s at the time was 70 million). The plague would eventually sweep West, killing at least 90 percent of the native population. For comparison’s sake, the Black Plague killed off between 30 and 60 percent of Europe’s population.

While this all might seem like some heavy history to lay on a bunch of second graders, your high school and college history books weren’t exactly in a hurry to tell you the full story. Which is strange, because many historians believe it is the single most important event in American history. But it’s just more fun to believe that your ancestors won the land by being the superior culture.

Getty

Getty

Yay for apocalypse profiteering!

European settlers had a hard enough time defeating the Mad Max-style stragglers of the once huge Native American population, even with superior technology. You have to assume that the Native Americans at full strength would have made it powerfully real for any pale faces trying to settle the country they had already settled. Of course, we don’t really need to assume anything about how real the American Indians kept it, thanks to the many people who came before the pilgrims. For instance, if you liked playing cowboys and Indians as a kid, you should know that you could have been playing vikings and Indians, because that actually happened. But before we get to how they kicked Viking ass, you probably need to know that …

#5. Native Culture Wasn’t Primitive

The Myth:

American Indians lived in balance with mother earth, father moon, brother coyote and sister … bear? Does that just sound right because of the Berenstain Bears? Whichever animal they thought was their sister, the point is, the Indians were leaving behind a small carbon footprint before elements were wearing shoes. If the government was taken over by hippies tomorrow, the directionless, ecologically friendly society they’d institute is about what we picture the Native Americans as having lived like.

“Our foreign policy can be summed up with one word: peyote.”

The Truth:

The Indians were so good at killing trees that a team of Stanford environmental scientists think they caused a mini ice age in Europe. When all of the tree-clearing Indians died in the plague, so many trees grew back that it had a reverse global warming effect. More carbon dioxide was sucked from the air, the Earth’s atmosphere held on to less heat, and Al Gore cried a single tear of joy.

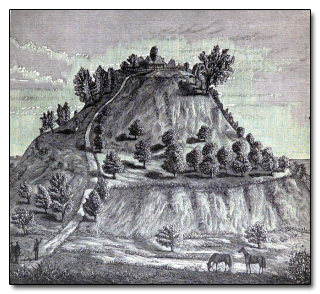

One of the best examples of how we got Native Americans all wrong is Cahokia, a massive Native American city located in modern day East St. Louis. In 1250, it was bigger than London, and featured a sophisticated society with an urban center, satellite villages and thatched-roof houses lining the central plazas. While the city was abandoned by the time white people got to it, the evidence they left behind suggests a complex economy with trade routes from the Great Lakes all the way down to the Gulf of Mexico.

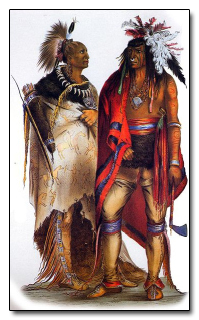

Contrary to what museums told us, the loin cloth was not the most advanced Native American technology.

And that’s not even mentioning America’s version of the Great Pyramid: Monk’s Mound. You know how people treat the very existence of the Great Pyramid in Egypt as one of history’s most confounding mysteries? Well, Cahokia’s pyramid dwarfs that one, both in size and in degree of difficulty. The mound contains more than 2.16 billion pounds of soil, some of which had to be carried from hundreds of miles away, to make sure the city’s giant monument was vividly colored. To put that in perspective, all 13 million people who live in the state of Illinois today would have to carry three 50-pound baskets of soil from as far away as Indiana to construct another one.

“What if turn our back on God?”

So why does Egypt get millions of dollars of tourism and Time Life documentaries dedicated to their boring old sand pyramids, while you didn’t even know about the giant blue, red, white, black, gray, brown and orange testament to engineering and human willpower just outside of St. Louis? Well, because the Egyptians know how to treat one of the Eight Wonders of the World. America, on the other hand, appears to be trying to figure out how to turn it into a parking lot.

But think of all the parking!

In the realm of personal hygiene, the Europeans out-hippied the Indians by a foul smelling mile. Europeans at the time thought baths attracted the black humors, because they never washed and were amazed by the Indians’ interest in personal cleanliness. The natives, for their part, viewed Europeans as “just plain smelly” according to first hand records.

The Native Americans didn’t hate Europeans just for the clouds of awfulness they dragged around behind them. Missionaries met Indians who thought Europeans were “physically weak, sexually untrustworthy, atrociously ugly” and “possessed little intelligence in comparison to themselves.” The Europeans didn’t do much to debunk the comparison in the physical beauty department. Verrazzano, the sailor who witnessed the densely populated East Coast, called a native who boarded his ship “as beautiful in stature and build as I can possibly describe,” before presumably adding, “you know, for a dude.” This man-crush wasn’t an isolated incident. British fisherman William Wood described the Indians in New England as “more amiable to behold, though dressed only in Adam’s finery, than … an English dandy in the newest fashion.” Or,“Better looking than any of us, and they’re not even trying.”

Getty

Getty

“Oh yeah, this is just my walkin’ around paint.”

OK, now that we got that out of the way, we can tell you about the historical slash-fiction your history teacher forgot to tell you actually

happened.

#4. Columbus Didn’t Discover America: Vikings vs. Indians

The Myth:

America was discovered in 1492 because Europeans were starting to get curious about the outside world thanks to the Renaissance and Enlightenment and Europeans of the time just generally being the first smart people ever. Columbus named the people who already lived there Indians, presumably because he was being charmingly self-deprecating.

“I don’t know what we’ll call the people from actual India. That’s the future’s problem.”

The Truth:

Here’s what we know. A bunch of vikings set up a successful colony in Greenland that lasted for 518 years (982-1500). To put that into perspective, the white European settlement currently known as the United States will need to wait until the year 2125 to match that longevity. The vikings spent a good portion of that time sending expeditions down south to try to settle what they called Vineland — which historians now believe was the East Coast of North America. Some place the vikings as far south as modern day North Carolina.

“The South will pillage again!”

After spending a couple decades sneaking ashore to raid Vineland of its ample wood pulp, the vikings made a go of settling North America in 1005. After landing there with livestock, supplies and between 100 and 300 settlers, they set up the first successful European American colony … for two years. And then the Native Americans kicked out of the country, shooting the head viking in the heart with an arrow.

So to recap, the vikings discovered America. They were camping off the coast of America, and had every reason to settle America for about 500 years. Despite being the biggest badasses in European history, one tangle with the natives was enough to convince the vikings that settling America wasn’t worth the trouble. If you think the pilgrims would have fared any better than the vikings against an East Coast chock-full of Native Americans, you either don’t know what a viking is or you’re placing entirely too much stock in the strategic importance of having belt buckles on your shoes.

If the Indians had been at full strength in 1640, white people might still be sneaking onto the East Coast to steal wood pulp. That’s as far as the vikings got in 500 years, and they were sailing from much closer than Europe and desperately needed the resources — the two competing theories for why the viking settlements on Greenland eventually died out are lack of resources and getting killed by natives — and, perhaps most importantly, they were vikings.

So why did your history teachers lie? This should have been history teachers’ version of dinosaurs: a mostly unknown period of violent awesomeness they nevertheless told you about because they knew it would hook every male between the ages of 5 and 12 forever.

Consider this one a freebie, Hollywood.

It turns out that many of the awesomest stories had to be paved over by the lies you memorized in order to protect your teachers and parents from awkward conversations. Like the one about how …

#3. Everything You Know About Columbus Is a Calculated Lie

The Myth:

Columbus discovered America thanks to a daring journey across the Atlantic. His crew was about to throw him overboard when land was spotted. Even after he landed in America, Columbus didn’t realize he’d discovered an entire continent because maps of America were far less reliable back then. In one of the great tragedies of history, Columbus went to his grave poor, believing he’d merely discovered India. Nobody really “got” America’s potential until the pilgrims showed up and successfully settled the country for the first time. Nearly 150 years might seem like a long time between trips, but boats were really slow back in those days, and they’d just learned that the Atlantic Ocean went that far.

“Pile into a tiny boat with dozens of filthy people for months on end” isn’t the world’s most attractive sales pitch.

The Truth:

First of all, Columbus wasn’t the first to cross the Atlantic. Nor were the vikings. Two Native Americans landed in Holland in 60 B.C. and were promptly not given a national holiday by anyone. Columbus didn’t see the enormous significance of his ability to cross the Atlantic because it wasn’t especially significant. His voyage wasn’t particularly difficult. They enjoyed smooth sailing, and nobody was threatening to throw him overboard. Despite what history books tell kids (and the Internet apparently believes), Columbus died wealthy, and with a pretty good idea of what he’d found — on his third voyage to America, he wrote in his journal, “I have come to believe that this is a mighty continent which was hitherto unknown.”

“Unknown” in this context means “inhabited by tens of millions.”

The myths surrounding him cover up the fact that Columbus was calculating, shrewd and as hungry for gold as the voice over guy in the Cash4Gold ads. When he couldn’t find enough of the yellow stuff to make his voyage profitable, he focused on enslaving Native Americans for profit. That’s how efficient Columbus was — he discovered America and invented American slavery in the same 15-year span.

There were plenty of unsuccessful, mostly horrible attempts to settle America between Columbus’ discovery and the pilgrims’ arrival. We only hear these two “settling of America” stories because history books and movies aren’t huge fans of what white people got up to between 1492 and 1620 in America — mostly digging for gold and eating each other.

Getty

Getty

When people talk about traditional American values, this is what they mean.

They also show us white Europeans being unable to easily defeat a native population that hadn’t yet been ravaged by plague. It wasn’t coincidence that the pilgrims settled America two years after New England was emptied of 96 percent of the Indians who lived there. According to James W. Loewen’s Lies My Teacher Told Me, that’s generally how the settling process went: The plague acted as a lead blocker for white European settlers, clearing the land of all the natives. The Europeans had superior weapons, but they also had superior guns when they tried to colonize China, India, Africa and basically every other region on the planet. When you picture Chinese or Indian or African people today, they’re not white because those lands were already inhabited when the Europeans showed up. And so was America.

American history goes to almost comical lengths to ignore that fact. For instance, if your reading comprehension was strong in middle school, you might remember the lost colony of Roanoke, where the people mysteriously disappeared, leaving behind only one cryptic clue: the word “Croatan” carved into the town post. As we’ve covered before, this is only a mystery if you are the worst detective ever. Croatan was the name of a nearby island populated by friendly Native Americans. In the years after the people of Roanoke “disappeared,” genetically impossible Native Americans with gray eyes and an “astounding” familiarity with distinctly European customs began to pop up in the tribes that moved between Croatan and Roanoke islands.

“It must be written in a cypher of some sort. Let’s just go ahead and call it alien abduction.”

#2. White Settlers Did Not Carve America Out of the Untamed Wilderness

The Myth:

The pilgrims were the first in a parade of brave settlers who pushed civilization westward along the frontier with elbow grease and sheer grizzled-old-man strength.

The Truth:

In written records from early colonial times, you constantly come across “settlers” being shocked at how convenient the American wilderness made things for them. The eastern forests, generally portrayed by great American writers as a “thick, unbroken snarl of trees” no longer existed by the time the white European settlers actually showed up. The pilgrims couldn’t believe their luck when they found that American forests just naturally contained “an ecological kaleidosocope of garden plots, blackberry rambles, pine barrens and spacious groves of chestnut, hickory and oak.”

Getty

Getty

“We have hours of weeding ahead of us, but by the grace of God, we will persevere.”

The puzzlingly obedient wilderness didn’t stop in New England. Frontiersmen who settled what is today Ohio were psyched to find that the forest there naturally grew in a way that “resembled English parks.” You could drive carriages through the untamed frontier without burning a single calorie clearing rocks, trees and shrubbery.

Whether they honestly believed they’d lucked into the 17th century equivalent of Candyland or were being willfully ignorant about how the land got so tamed, the truth about the presettled wilderness didn’t make it into the official account. It’s the same reason every extraordinarily lucky CEO of the past 100 years has written a book about leadership. It’s always a better idea to credit hard work and intelligence than to acknowledge that you just got luckier than any group of people has ever gotten in the history of the world.

“ iIt’s already wired for Wi-Fi!”

Nobody’s role in settling America has been quite as overplayed as the pilgrims’. Despite famous sermons with titles like “Into the Wilderness,” the pilgrims cherry-picked Plymouth specifically because it was a recently abandoned town. After sailing up and down the coast of Cape Cod, they chose Plymouth Rock because of “its beautiful cleared fields, recently planted in corn, and its useful harbor.”

We’re always told that the pilgrims were helped by an Indian named Squanto who spoke English. How did that happen? Had he taken AP English in high school? The answer to that question is the greatest story your history teachers didn’t bother to teach you. Squanto was from the town that would become Plymouth, but between being born there and the pilgrims’ arrival, he’d undergone an epic journey that puts Homer’s Odyssey to shame.

And at the end,

he had to teach white people how to bury dead fish with corn kernels.

Squanto had been kidnapped from Cape Cod as a child and sold into slavery in Spain. He escaped like the boy Maximus he was, and spent his better years hoofing it west until he hit the Atlantic Ocean. Deciding that swimming back to America would take too much time, he learned enough English to convince someone to let him hitch a ride to “the New World.” When he finally got back home, he found his town deserted. The plague had swept through two years before, taking everyone but him with it.

When the pilgrims showed up, instead of being angry at the people from the Continent who had stolen his ability to grow up with his family, he decided that since nobody else was using it, he might as well show them how to make his town work.

Go bathe in the sea, you are dirty.Getty

This is especially charitable of him when you realize that, while the pilgrims were nicer than past settlers, they weren’t exactly sensitive to Squanto’s plight. According to a pilgrim journal from the days immediately after they arrived, they raided Indian graves for “bowls, trays, dishes and things like that. We took several of the prettiest things to carry away with us, and covered the body up again.” And yet Squanto taught them how to make it through a winter without turning to cannibalism — a landmark accomplishment for the British to that point.

Compare that to Jamestown, the first successful settlement in American history. You don’t know the name of the ship that landed there because the settlers antagonized the natives, just like the vikings who came before them. The Native Americans didn’t have to actively kill them. They just sat back and laughed as the English spent the harvest seasons digging holes for gold. The first Virginians were so desperate without a Squanto that they went from taking Indian slaves to offering themselves up as slaves to the Indians in exchange for food. Enough English managed to survive there to make Jamestown the oldest successful colonial settlement in America. But it’s hard to turn it into a religious allegory in which white people are the good guys, so we get the pilgrims instead.

Getty

Getty

If this were accurate, the settlers would be in bushes

.

#1. How Indians Influenced Modern America

The Myth:

After the natives helped the pilgrims get through that first winter, all playing nice disappeared until Dances with Wolves. Even the movies that do portray white people going native portray it as a shocking exception to the rule. Otherwise, the only influence the natives seem to have on the New World and the frontiersmen is giving them moving targets to shoot at, and eventually a plot outline for Avatar.

Getty

Getty

It’s pretty much just this and Kevin Costner until Wounded Knee.

The Truth:

The fake mystery of Roanoke is a pretty good key for understanding the difference between how white settlers actually felt about American Indians and how hard your history books had to ignore that reality. Settlers defecting to join native society was so common that it became a major issue for colonial leaders — think the modern immigration debate, except with all the white people risking their lives to get out of American society. According to Loewen, “Europeans were always trying to stop the outflow. Hernando De Soto had to post guards to keep his men and women from defecting to Native societies.” Pilgrims were so scared of Indian influence that they outlawed the wearing of long hair.

Ben Franklin noted that, “No European who has tasted Savage Life can afterwards bear to live in our societies.” While “always bet on black” might have been sound financial advice by the time Wesley Snipes offered it, Ben Franklin knew that for much of American history, it was equally advisable to bet on red.

Getty

Getty

Franklin wasn’t pointing this out as a critique of the settlers who defected — he believed that Indian societies provided greater opportunities for happiness than European cultures — and he wasn’t the only Founding Father who thought settlers could learn a thing or two from them. They didn’t dress up like Indians at the Boston Tea Party ironically. That was common protesting gear during the American revolutions.

For a hundred years after the American Revolution, none of this was a secret. Political cartoonists used Indians to represent the colonial side. Colonial soldiers dressed up like Indians when fighting the British. Documents from the time indicate that the design of the U.S. government was at least partially inspired by native tribal society. Historians think the Iroquois Confederacy had a direct influence on the U.S. Constitution, and the Senate even passed a resolution acknowledging that “the confederation of the original thirteen colonies into one republic was influenced … by the Iroquois Confederacy, as were many of the democratic principles which were incorporated into the constitution itself.”

If we’d incorporated their fashion sense, C-SPAN would be more interesting.

That wasn’t just Congress trying to get some Indian casino money. The colonists came from European countries that had spent most of their time as monarchies and much of their resources fighting religious wars with each other. They initially tried to set up the colonies exactly like Western Europe — a series of small, in-fighting nations stacked on top of each other. The idea of an overarching confederacy of different independent states was completely foreign to them. Or it would have been. But as Ben Franklin noted in a letter about the failure to integrate with one another:

“It would be a strange thing if six nations of ignorant savages should be capable of forming a scheme for such a union and be able to execute it in such a manner as that it has subsisted ages and appears insoluble; and yet that a like union should be impracticable for 10 or a dozen English colonies.”

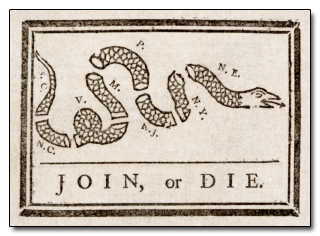

Join, or die (or plagiarize from the Indians).

In 1987, Cornell University held a conference on the link between the Iroquois’ government and the U.S. Constitution. It was noted that the Iroquois Great Law of Peace “includes ‘freedom of speech, freedom of religion … separation of power in government and checks and balances.”

Wow, checks and balances, freedom of speech and religion. Sounds awfully familiar.

One of the strangest legacies of America’s founding is our national obsession with the apocalypse. There’s a new JJ Abrams show coming this fall called The Revolution about a post-apocalyptic America, and of course The Hunger Games. We go to a gift shop in Arizona and see dug-up Indian arrowheads, and never think “this is the same thing as the stuff laying around in Terminator or The Road or that part in The Road Warrior where the feral kid finds a music box and doesn’t know what it is.”

We love the apocalypse as long as nobody acknowledges the truth: It’s not a mythical event. We live on top of one.