German Victims : How the Allied Victors of WWII tortured and killed their German prisoners (Part 1 of 2)

This terrifying article will make you ask the forbidden question:

“Did the victors of WWII deserve to win?”

By Thomas Goodrich

author of Hellstorm—The Death of Nazi Germany, 1944-1947

An edited abridgement by Lasha Darkmoon with notes and comments

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

“Staffed and run by Jews, the prisons were little better than torture chambers.”

— Thomas Goodrich

Part 1: Vai Victis! — Woe to the Vanquished!

Moments after arrival at the prison camp, prisoners were made horrifyingly aware of their fate. John Sack, himself a Jew, reports on one camp run by twenty-six-year-old Shlomo Morel.

“I was at Auschwitz,” Shlomo proclaimed, lying to the Germans but, even more, to himself, psyching himself up like a fighter the night of the championship, filling himself with hate for the Germans around him. “I was at Auschwitz for six long years, and I swore that if I got out, I’d pay all you Nazis back!”

Note by Lasha Darkmoon: Shlomo Morel, psychopathic torturer and killer of German prisoners of war, later took refuge in Israel where he was held in high honor and remained beyond the reach of international law. Here now is this Jewish war criminal in 1945, age 26, commandant of a German prisoner of war camp where torture was practiced for its own sake:

“Schweine!” Shlomo cried. He threw down his rubber club, grabbed a wooden stool, and started beating a German’s head. Without thinking, the man raised his arms, and Shlomo, enraged that the man would try to evade his just punishment, cried, “Sonofawhore!” and slammed the stool against the man’s chest.

The man dropped his arms, and Shlomo started hitting his now undefended head when snap! the leg of the stool split off. Cursing the German birchwood, he grabbed another stool and hit the German with that.

No one was singing now, but Shlomo, shouting, didn’t notice.

The other guards called out, “Blond!” “Black!” “Short!” “Tall!” and as each of these terrified people came up, they wielded their clubs upon him. The brawl went on till eleven o’clock, when the sweat-drenched invaders cried, “Pigs! We will fix you up!” and left the Germans alone.

Some were quite fixed. Shlomo and his subordinates had killed them

The next night it was more of the same . . . and the next night . . . and the next and the next. Those who survived the “welcoming committees” at this and other camps were flung back into their pens.

And so, with the once mighty German Army now disarmed and enslaved in May, 1945, and with their leaders either dead or awaiting trial for so-called “war crimes,” the old men, women and children who remained in the dismembered Reich found themselves utterly at the mercy of the victors.

Unfortunately for these survivors, never in the history of the world was mercy in shorter supply.

§

Because their knowledge of the language and culture was superb, most of the intelligence officers accompanying US and British forces into the Reich after WWII were Jewish refugees who had fled Germany in the late 1930s. Although their American and English “aides” were hardly better, the fact that many of these people became interrogators, examiners and screeners, with old scores to settle, insured that no German would be shown any mercy.

One man opposed to the vengeance-minded program of these Americanized Jews was General George Patton.

“Evidently the virus started by Morgenthau and [Bernard] Baruch of a Semitic revenge against all Germans is still working,” wrote the general in private. “I am frankly opposed to this war-criminal stuff. It is not cricket and it is Semitic. I can’t see how Americans can sink so low.”

Soon after occupation, all adult Germans were compelled to register at the nearest Allied headquarters and complete a lengthy questionnaire on their past activities. While many nervous citizens were detained then and there, most returned home, convinced that at long last the terrible ordeal was over. For millions, however, the trial had but begun.

Few German adults, Nazi or not, escaped the dreaded knock on the door. Far from being dangerous fascists, Freddy and Lali Horstmann were actually well-known anti-Nazis. Lali Horstmann records her encounter with a Russian commissar from the Russian Zone.

LD: Since a disproportionate number of Russian commissars were Jews, especially those working for the cheka and other security services, this particular officer was probably been Jewish.

“I am sorry to bother you,” he began, “but I am simply carrying out my orders. Until when did you work for the Foreign Office?”

“Till 1933,” my husband answered.

“Then you need fear nothing,” Androff said. “We accuse you of nothing, but we want you to accompany us to the headquarters of the NKVD, the secret police, so that we can take down what you said in a protocol, and ask you a few questions about the working of the Foreign Office.”

We were stunned for a moment; then I started forward, asking if I could come along with them. “Impossible,” the interpreter smiled. My heart raced. Would Freddy answer satisfactorily? Could he stand the excitement? What sort of accommodation would they give him?

“Don’t worry, your husband has nothing to fear,” Androff continued. “He will have a heated room. Give him a blanket for the night, but quickly, we must leave.”

There was a feeling of sharp tension, putting the soldier on his guard, as though he were expecting an attack from one of us. I took first the soldier, then the interpreter, by their hands and begged them to be kind to Freddy, repeating myself in the bustle and scraping of feet that drowned my words.

There was a banging of doors. A cold wind blew in. I felt Freddy kiss me.

I never saw him again.

§

“We were wakened by the sound of tires screeching, engines stopping abruptly, orders yelled, general din, and a hammering on the window shutters. Then the intruders broke through the door, and we saw Americans with rifles who stood in front of our bed and shone lights at us. None of them spoke German, but their gestures said: ‘Get dressed, come with us immediately.’ This was my fourth arrest.”

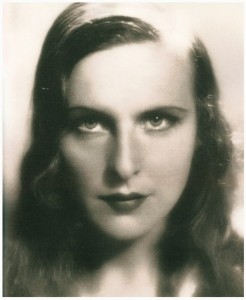

So wrote Leni Riefenstahl, a talented young woman who was perhaps the world’s greatest film-maker.

Because her epic documentaries—Triumph of the Will and Olympia—seemed paeans to not only Germany, but National Socialism, and because of her close relationship with an admiring Adolf Hitler, Leni was of more than passing interest to the Allies. Though false rumors also hinted that the attractive, one-time actress was also a “mistress of the devil”—that she and Hitler were lovers.

“Neither my husband nor my mother nor any of my three assistants had ever joined the Nazi Party, nor had any of us been politically active,” said the confused young woman. “No charges had ever been filed against us, yet we were at the mercy of the Allies and had no legal protection of any kind.”

“We were never free from torments [in the American prison]. For hours on end I rolled about on my bed, trying to forget my surroundings, but it was impossible. The mentally disturbed woman kept screaming — all through the night. But even worse were the yells and shrieks of men from the courtyard, men who were being beaten, screaming like animals.”

Soon after Leni’s fourth arrest, came a fifth.

The jeep raced along the autobahns until, a few hours later, I was brought to the Salzburg Prison. There an elderly prison matron rudely pushed me into the cell, kicking me so hard that I fell to the ground. Then the door was locked. There were two other women in the dark, barren room, and one of them, on her knees, slid about the floor, jabbering confusedly; then she began to scream, her limbs writhing hysterically. She seemed to have lost her mind. The other woman crouched on her bunk, weeping to herself.

As Leni Riefelstahl (pictured) and others quickly discovered, the “softening up” process began soon after arrival at an Allied prison.

As Leni Riefelstahl (pictured) and others quickly discovered, the “softening up” process began soon after arrival at an Allied prison.

When Ernst von Salomon, his Jewish girl friend and fellow prisoners reached an American holding pen near Munich, the men were promptly led into a room and brutally beaten by military police.

With his teeth knocked out and blood spurting from his mouth, von Salomon moaned to a gum-chewing officer, “You are no gentlemen.” The remark brought only a roar of laughter from the attackers. “No, no, no!” the GIs grinned. “We are Mississippi boys!”

In another room, military policemen raped the women at will while leering soldiers watched from windows. After such savage treatment, the feelings of despair only intensified once the captives were crammed into cells.

“The people had been standing there for three days, waiting to be interrogated,” remembered a German physician ordered to treat prisoners in the Soviet Zone. “At the sight of us a pandemonium broke out which left me helpless. As far as I could gather, the usual senseless questions were being reiterated: Why were they there, and for how long? They had no water and hardly anything to eat. They wanted to be let out more often than once a day. A great many of them have dysentery so badly that they can no longer get up.”

“Young Poles made fun of us,” said a woman from her cell in the same zone. “They threw bricks through the windows, paper bags with sand, and skins of hares filled with excrement. We did not dare to move or offer resistance, but huddled together in the farthest corner, in order not to be hit, which could not always be avoided. . . . We were never free from torments.”

“For hours on end I rolled about on my bed, trying to forget my surroundings,” recalled Leni Riefenstahl, “but it was impossible. The mentally disturbed woman kept screaming—all through the night. But even worse were the yells and shrieks of men from the courtyard, men who were being beaten, screaming like animals. I subsequently found out that a company of SS men was being interrogated.

They came for me the next morning, and I was taken to a padded cell where I had to strip naked, and a woman examined every square inch of my body. Then I had to get dressed and go down to the courtyard, where many men were standing, apparently prisoners, and I was the only woman.

We had to line up before an American guard who spoke German. The prisoners stood to attention, so I tried to do the same, and then an American came who spoke fluent German. He pushed a few people together, then halted at the first in our line.

“Were you in the Party?”

The prisoner hesitated for a moment, then said, “Yes.” He was slugged in the face and spat blood.

The American went on to the next in line.

“Were you in the Party?”

The man hesitated.

“Yes or no?”

“Yes.”

And he too got punched so hard in the face that the blood ran out of his mouth. However, like the first man, he didn’t dare resist.

They didn’t even instinctively raise their hands to protect themselves. They did nothing. They put up with the blows like dogs.

The next man was asked: “Were you in the Party?”

Silence.

“Well?”

“No,” he yelled, so no punch.

From then on nobody admitted that he had been in the Party and I was not even asked.

As the above case illustrated, there often was no rhyme or reason to the examinations. All seemed designed to force from the victim what the inquisitor wanted to hear, whether true or false. Additionally, most such “interrogations” were structured to inflict as much pain and suffering as possible. One prisoner explained:

“The purpose of these interrogations is not to worm out of the people what they knew—which would be uninteresting anyway—but to extort from them special statements. The methods resorted to are extremely primitive. People are beaten up until they confess to having been members of the Nazi Party. The authorities simply assume that, basically, everybody has belonged to the Party. Many people die during and after these interrogations, while others, who admit at once their party membership, are treated more leniently.”

“A young commissar, who was a great hater of the Germans, cross-examined me,” said Gertrude Schulz. “When he put the question: ‘Frauenwerk [Women’s Labor Service]?’ I answered in the negative. Thereupon he became so enraged, that he beat me with a stick, until I was black and blue. I received about 15 blows … on my left upper arm, on my back and on my thigh. I collapsed and, as in the case of the first cross-examination, I had to sign the questionnaire.”

“Both officers who took our testimony were former German Jews,” reminisced a member of the women’s SS, Anna Fest. While vicious dogs snarled nearby, one of the officers screamed questions and accusations at Anna. If the answers were not those desired, “he kicked me in the back and the other hit me.”

They kept saying we must have been armed, have had pistols and so on. But we had no weapons, none of us. I had no pistol. I couldn’t say, just so they’d leave me in peace, ‘Yes, we had pistols.’ The same thing would happen to the next person to testify. The terrible thing was, the German men had to watch. That was a horrible, horrible experience. That must have been terrible for them. When I went outside, several of them stood there with tears running down their cheeks. What could they have done? They could do nothing.

Not surprisingly, with beatings, rape, torture, and death facing them, few victims failed to “confess” and most gladly inked their name to any scrap of paper shown them. Some, like Anna, tried to resist. Such recalcitrance was almost always of short duration, however. Generally, after enduring blackened eyes, broken bones, electric shock to breasts—or, in the case of men, smashed testicles—only those who died during torture failed to sign confessions.

Alone, surrounded by sadistic hate, utterly bereft of law, many victims understandably escaped by taking their own lives. Like tiny islands in a vast sea of evil, however, miracles did occur. As he limped painfully back to his prison cell, one Wehrmacht officer reflected on the insults, beatings, and tortures he had endured and contemplated suicide.

I could not see properly in the semi-darkness and missed my open cell door. A kick in the back and I was sprawling on the floor. As I raised myself I said to myself I could not, should not accept this humiliation. I sat on my bunk. I had hidden a razor blade that would serve to open my veins. Then I looked at the New Testament and found these words in the Gospel of St. John: “Without me ye can do nothing.”

Yes. You can mangle this poor body—I looked down at the running sores on my legs—but myself, my honor, God’s image that is in me, you cannot touch. This body is only a shell, not my real self. Without Him, without the Lord, my Lord, ye can do nothing. New strength seemed to rise in me.

I was pondering over what seemed to me a miracle when the heavy lock turned in the cell door. A very young American soldier came in, put his finger to his lips to warn me not to speak. “I saw it,” he said. “Here are baked potatoes.” He pulled the potatoes out of his pocket and gave them to me, and then went out, locking the door behind him.

§

Horrific as de-Nazification was in the British, French and, especially the American Zone, it was nothing compared to what took place in Poland, behind Soviet lines.

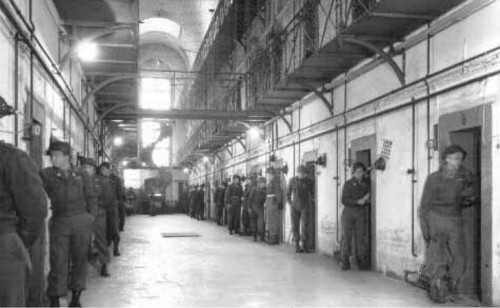

In hundreds of concentration camps sponsored by an apparatus called the “Office of State Security,” thousands of Germans—male and female, old and young, high and low, Nazi and non–Nazi, SS, Wehrmacht, Volkssturm, Hitler Youth, all—were rounded up and imprisoned.

While those with blond hair, blue eyes and handsome features were first to go, anyone who spoke German would do.

AMERICAN TORTURE PEN

“Staffed and run by Jews, with help from Poles, Czechs, Russians, and other concentration camp survivors, the prisons were little better than torture chambers where dying was a thing to be prolonged, not hastened.” — Thomas Goodrich

http://www.darkmoon.me/2015/german-victims-how-the-allied-victors-of-wwii-tortured-and-killed-their-german-prisoners-part-1-of-2/