'Why Your Health Care Is so Darn Expensive'…

Contributed by Alex Daley and Doug Hornig, Senior Editors, Casey Extraordinary Technology

The cellphone in your pocket is NASA-smart. Yet it costs just a couple hundred dollars. So why is it that rising technical capabilities are leading to drastically falling prices happening everywhere, except in your medical bill? The answer may surprise you…

Microchip technology breakthroughs mean you can now do more on a phone bought for $200 than you ever could have thought of doing on a $2,000 computer just a decade ago. It has more computer power than all of NASA had back in 1969 – the year it sent two astronauts to the moon. The $300 Sony Playstation in the kids' room has the power of a military supercomputer of 1997, which cost millions of dollars.

So just think what computers can do to help doctors cure you when you're sick. Indeed, computers do keep us healthier and living longer. Illnesses are diagnosed faster. Computer scans catch killer diseases earlier, giving the patient a better survival rate than ever in history. New treatments are being created at an astonishing rate. All kinds of conditions that would have killed you a decade ago now are controlled and even cured, thanks to new technology.

But shouldn't medical care – just like the mobile phone and video games – be getting cheaper?

"The bottom line is that you are paying for extending your life and curing diseases that until recently would likely have killed you."

A longer life has a bigger price ticket.

But are We Really Living That Much Longer?

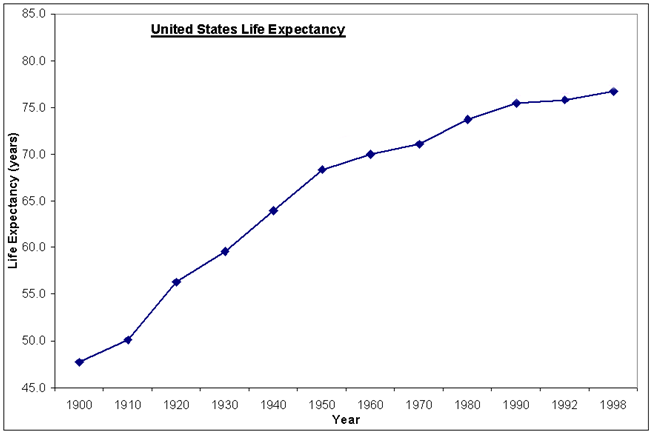

It is easy to dismiss the days of people's lives spanning a mere three decades as prehistoric... but it wasn't really that long ago. According to data compiled by the World Health Organization, the average global lifespan as recently as the year 1900 was just 30 years. And if you were lucky enough to be born in the richest few countries on Earth at the time, the number still rarely crossed 50.

Curing the Six Killer Diseases of Childhood

It was just about that time that public health came into its own, with major efforts from both the private and public sectors. In 1913, the Rockefeller Foundation was looking for diseases that might be controlled or perhaps even eradicated in the space of a few years or a couple of decades. The result of this concerted public-health push included nearly eradicating smallpox, leprosy, and other debilitating or deadly diseases. It also included vaccines against the six killer diseases of childhood: tetanus, polio, measles, diphtheria, tuberculosis, and whooping cough. A simple graph illustrates the dramatic change.

In the US, the average lifespan is now 78.2 years, according to the World Bank. In many countries in the world, it is well over 80. But like all averages, it's affected mainly by the extremes. For instance, in the early part of the 1900s, the data point that weighed most heavily on average lifespans was child mortality. Back then families were much larger, and parents routinely expected some of their children to die.

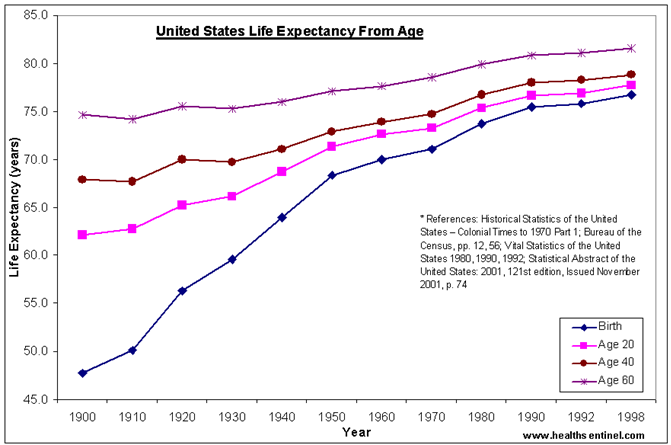

But the flip side, as can be seen in the graph, is that for anyone lucky enough to survive childhood at the turn of the last century, life expectancy was not that much lower than it is today.

For all of our advances in medicine, we only live about 20 to 30% longer.

Not only is the increase quite small – relative, say, to the explosion in computing power over the same period of time – the amount of money we spend adding another year or two to the average lifespan is on the rise.

If we exclude high child mortality, we are not living that much longer today than we once were. So where does all the money we spend actually go?

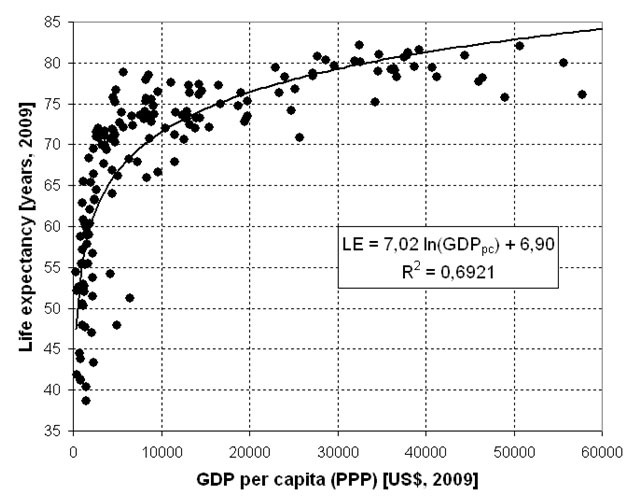

Intuitively, one would think that there should be a relationship between the economic well-being of a country and the life expectancy of its citizens. And, as you would imagine, there is a strong correlation between wealth and health.

The important takeaway from this graph is the flattening of the curve along the top. What it means is that in many countries with lower GDPs, those with less to spend on health care can attain life expectancies in the 65-75 range. Pushing the boundaries beyond that (as the richer countries do) clearly requires much greater resources. By implication, that means spending more to do it.

Here's something else we've discovered: The cost of battling the diseases of adulthood rises dramatically with age. Per capita lifetime healthcare expenditure in the US is $316,600, a third higher for females ($361,200) than males ($268,700). But two-fifths of this difference owes entirely to women's longer life expectancy.

Nearly one-third of lifetime expenditures is incurred during middle age, and nearly half during the senior years. And for survivors to age 85, more than one-third of their lifetime expenditures will accrue in just the years they have left.

Technologies and the cutting-edge companies that create them help to drive these costs down, while creating a profitable business for themselves and their investors.

To take a simple example, the MRI machine invented by Raymond V. Damadian may seem expensive on the surface, but it accomplishes things that previously required a much heavier investment in time and diverse professional expertise.

Or consider how a company like NxStage Medical a company the team at Casey Extraordinary Technology have been following closely and profiting handsomely from for quite some time. A business like this has revolutionized the delivery of renal care. Their home-based units save a ton of money compared with the traditional, thrice-weekly visits to a special dialysis clinic.

Innovations like these from NxStage are changing the way patients receive care and the way a company produces income for its shareholders.

But the problem remains that overall, medical costs continue to rise faster than improved technology can serve as a countervailing force.

There are three easily identifiable reasons for this:

- Diminishing marginal returns

- Rising costs of non-technology inputs

- Increased quality of life

The Law of Decelerating Returns

Technology in most arenas is a field of rapidly increasing marginal return on investment, i.e., accelerating change. In other words, things don't just get continually better or cheaper; they tend to get better or cheaper at a faster rate over time. This concept of "economies of scale" applies in finance, hard sciences, and any sufficiently quantitative field – where numbers dictate behavior. It mainly refers to the idea of changing returns over time. We refer to these as "marginal returns."

Imagine for a moment that you are a manufacturer:

- Once you've paid off the cost of your factory or equipment – your "fixed" costs – you maybe make a widget to sell for $10, with a cost per unit of $5.

- If you make and sell a thousand units, you make $5,000 profit. That is the marginal return.

- But now imagine that if you make 100,000 units, your cost per unit drops to $4 – you have more negotiating power over your raw materials suppliers, you can run your staff with less slack, etc.

-

And if you can make 200,000 you save/make another dollar.

That means you have "accelerating marginal returns" – we're used to that in technology.

Every year Intel is able to lower the cost of the processing power it sells on the market. A chip is a commodity product: it's the same for nearly all consumers, and the market is global. Of course medicine is not quite the same – at least not in the most important instances.

No doctor treats a wide range of diseases. They're forced to specialize and must undergo never-ending education and certification. And they require complex equipment used only by a handful of fellow specialists. Ultimately, there are few places to find economies of scale.

Treatment Difficulties

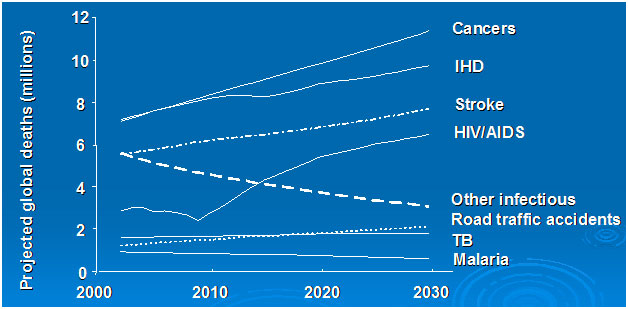

The simple fact is that, in our zeal to live to the age of 80+, we have made a trade-off. We've left behind the diseases of youth – diseases that mostly strike once, resulting either in death or fading chances of a long life – but they've been replaced by a host of new, chronic diseases. Diseases of age. Diseases of environment. And diseases of design.

These are the challenges companies like NxStage are dealing with every day. It's a time-intensive endeavor, but successful medicines are big winners for investors... sometimes very big.

The illnesses we fall prey to these days as a result of living longer – conditions such ischemic heart disease or cancer – are all much more complicated than their predecessors. None is caused by a single, easily identifiable agent. There's no virus to isolate and eradicate. There's no pathogen sample to convert to a vaccine.

These conditions cost considerably more to treat than the traditional infectious disease does. More labor is involved. More time. And available drug treatments rarely cure in a few doses, if ever.

So, chronic conditions breed chronic costs.

Keeping someone with lung cancer alive for twice as long as would have been the case 30 years ago is a great feat, but it comes at considerable additional cost in terms of the time devoted by the many healthcare professionals involved. And that means troubling questions like this must be asked: If every patient can live twice as long, but it takes twice as many net people-hours to care for them, has there been a net gain for society?

The Driving Force

Our medical progress has been won through a major increase in net costs per person. In 1987, US per capita spending on health care was $2,051. That's $3,873 in 2009 dollars. But in 2009, actual spending amounted to $7,960 per capita. Some of that is attributable to rising costs that have outpaced inflation.

In 1986, the average pharmacist made $31,600, or $66,260 in 2012 dollars. Today, the real average salary is $115,181 – nearly double.

But it's not universal. Radiologists, for example, have seen their salaries drop from an inflation-adjusted $425,000+ to $386,000 in the same period.

Also, costs for surgeries and diagnostics are not a clear-cut contributor. Data are hard to compile as costs vary greatly:

- California recently saw charges for appendectomies in the range of $1,500 to $180,000.

- In Dallas, getting an MRI at one center can be more than 50% more expensive than another across town.

Most indications seem to point to lower, not higher, real costs over time for most common conditions. Average hospital stays post appendectomies have fallen from 4.8 to just 2.3 days in the past 25 years, for instance. That's thanks largely to insurance requirements, as well as better sutures, pain medicines, and surgical equipment.

As hard as procedural costs are to compare, the outcomes are much more clear-cut. In cancer, the improvement has been significant in some cases and less dramatic in others.

For those diagnosed with cancer in 1975-'77, the five-year survival rate was 49.1% (and only 41.9% for males).

For those diagnosed between 2001 and 2007, five-year survival increased to 67.4% for both sexes and jumped to 68.1% for men.

Even if you're diagnosed when over age 65, you have a 58.4% probability of living another five years.

Prognoses, however, vary widely with disease specifics. If you contract pancreatic cancer, for instance, your prospects are the grimmest. It's likely to be terminal very quickly. Among the most recently diagnosed cohort, a meager 5.6% survived for five years. That's more than double the rate from 30 years ago, but small comfort.

Liver cancer sufferers' five-year survival rate has more than quadrupled, but only from 3.4 to 15%.

Lung cancer is also still a near-certain killer. In the 2001-'07 group, a meager 16.3% survived for five years, only a slight tick up from the 12.3% rate of 30 years ago.

Brain cancer is quite lethal as well, with only 34.8% surviving for five years today – more than 50% better than the 22.4% rate of 30 years ago, but not great.

On the other side of the ledger, breast-cancer victims are doing very well. 90% survive for at least five years if diagnosed after 2001, vs. 75% in 1975-'77.

And prostate-cancer treatments have been the most spectacularly successful. Five-year survival is fully 99.9% of those diagnosed in the past ten years, vs. only 68.3% in 1975-'77.

Longer survival rates are, of course, impossible to document in recently diagnosed patients, since we're not there yet. But to give you some idea, here are the 20-year survival rates for the above cancers, taken from the NCI's 1973-'98 database: Pancreas, 2.7%; liver, 7.6%; lung, 6.5%; brain, 26.1%; breast, 65%; and prostate, 81.1.%.

These are big steps forward. They enhance not only the length but the quality of life, as well. However, with each rising year of average age, we increase our medical expenses.

By eradicating the big childhood killers, we solved most of the easy problems. And so we live to face the much more complicated and much more expensive to treat diseases of age. At some point, it isn't lifestyle changes that are keeping us alive – it's machines and doctors and medicines doing a lot of the heavy lifting in order to grant us those precious extra days. All of that costs money.

So we are not dying of the most dreaded ailments as quickly as we once were. But that's not due to advances in curing the major chronic illnesses of our time – heart disease, diabetes, cancer, and AIDS. Instead, we've primarily extended the amount of time we can live with them.

Mexico's health minister, Dr. Julio Frenk, noted the irony here when he said, "In health, we are always victims of our own successes." We are living longer... and we're costing a lot more in the process.

Doug Hornig

Senior Editor

Doug Hornig is the editor of Casey Daily Resource Plus, a frequent contributor to both Casey Research's BIG GOLD, the go-to information source for Gold investors and Casey Daily Dispatch, a simple and fast way to keep up with the ever-changing investing landscape.

Doug is not just an investment writer, however. Doug is an Edgar Award nominee, a finalist for the Virginia Prize in both fiction and poetry, and the winner of several open literary competitions, including the 2000 Virginia Governor's Screenwriting contest.

Doug has authored ten books, done investigative journalism for Virginia's leading newspaper, and written articles for Business Week, The Writer, Playboy, Whole Earth Review, and other national publications.

Doug lives on 30 mountainous acres in a county that has 14,000 residents and a single stop light.

Alex Daley

Chief Technology Investment Strategist

Alex Daley is the senior editor of the technology investor's friend, Casey Extraordinary Technology.

In his varied career, he's worked as a senior research executive, a software developer, project manager, senior IT executive, and technology marketer.

He's an industry insider of the highest order, having been involved in numerous startups as an advisor to venture capital companies. He's a trusted advisor to the CEOs and strategic planners of some of the world's largest tech companies, and he's a successful angel investor in his own right, with a long history of spectacular investment successes.

http://www.testosteronepit.com/home/2012/7/22/why-your-health-care-is-so-darn-expensive.html