Painful Debilitating Disease More Devastating than Previously Recognized (with videos)

DR. Mercola

It is a much more devastating illness than previously appreciated. Most patients with rheumatoid arthritis have a progressive disability.

The natural course of rheumatoid arthritis is quite remarkable in that less than 1 percent of people with the disease have a spontaneous remission. Some disability occurs in 50-70 percent of people within five years after onset of the disease, and half will stop working within 10 years. The annual cost of this disease in the U.S. is estimated to be over $1 billion.

This devastating prognosis is what makes this novel form of treatment so exciting, as it has a far higher likelihood of succeeding than the conventional approach.

Over the years I have treated over 3,000 patients with rheumatic illnesses, including SLE, scleroderma, polymyositis and dermatomyositis.

Approximately 15 percent of these patients were lost to follow-up for whatever reason and have not continued with treatment. The remaining patients seem to have a 60-90 percent likelihood of improvement on this treatment regimen.

This level of improvement is quite a stark contrast to the typical numbers quoted above that are experienced with conventional approaches, and certainly a strong motivation to try the protocol I discuss below.

RA Can Be More Deadly than Heart Disease

There is also an increased mortality rate with this disease. The five-year survival rate of patients with more than thirty joints involved is approximately 50 percent. This is similar to severe coronary artery disease or stage IV Hodgkin's disease.

Thirty years ago, one researcher concluded that there was an average loss of 18 years of life in patients who developed rheumatoid arthritis before the age of 50.

Most authorities believe that remissions rarely occur. Some experts feel that the term "remission-inducing" should not be used to describe ANY current rheumatoid arthritis treatment, and a review of contemporary treatment methods shows that medical science has not been able to significantly improve the long-term outcome of this disease.

Dr. Brown Pioneered a Novel Approach to Treat RA

I first became aware of Doctor Brown's protocol in 1989 when I saw him on 20/20 on ABC. This was shortly after the introduction of his first edition of his book, The Road Back. Unfortunately, Dr. Brown died from prostate cancer shortly after the 20/20 program so I never had a chance to meet him.

My application of Dr. Brown's protocol has changed significantly since I first started implementing it. Initially, I rigidly followed Dr. Brown's work with minimal modifications to his protocol. About the only change I made was changing Tetracycline to Minocin. I believe I was one of the first physicians who recommended the shift to Minocin and most people who use his protocol now use Minocin.

In 1939, Dr. Sabin, the discoverer of the polio vaccine, first reported chronic arthritis in mice caused by a mycoplasma. He suggested this agent might cause human rheumatoid arthritis. Dr. Brown worked with Dr. Sabin at the Rockefeller Institute.

Dr. Brown was a board certified rheumatologist who graduated from Johns Hopkins medical school. He was a professor of medicine at George Washington University until 1970 where he served as chairman of the Arthritis Institute in Arlington, Virginia. He published over 100 papers in peer reviewed scientific literature.

He was able to help over 10,000 patients when he used this program, from the 1950s until his death in 1989, and clearly far more than that have been helped by other physicians using this protocol.

He found that significant benefits from the treatment require, on average, about one to two years.

I have treated nearly 3000 patients and find that the dietary modification I advocate, which I started to integrate in the early 1990's, accelerates the response rate to several months. I cannot emphasize strongly enough the importance of this aspect of the program.

Still, the length of therapy can vary widely.

In severe cases, it may take up to 30 months for patients to gain sustained improvement. One requires patience because remissions may take up to 3 to 5 years. Dr. Brown's pioneering approach represents a safer, less toxic alternative to many conventional regimens and results of the NIH trial have finally scientifically validated this treatment.

The dietary changes are absolutely an essential component of my protocol. Dr. Brown's original protocol was notorious for inducing a Herxheimer, or worsening of symptoms, before improvement was noted. This could last two to six months. Implementing my nutrition plan resulted in a lessening of that reaction in most cases.

When I first started using his protocol for patients in the late '80s, the common retort from other physicians was that there was "no scientific proof" that this treatment worked. Well, that is certainly not true today. A review of the bibliography will provide over 200 references in the peer-reviewed medical literature that supports the application of Minocin in the use of rheumatic illnesses.

In my experience, nearly 80 percent of people do remarkably better with this program. However, approximately 5 percent continue to worsen and require conventional agents, like methotrexate, to relieve their symptoms.

Scientific Proof for this Approach

The definitive scientific support for minocycline in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis came with the MIRA trial in the United States. This was a double blind randomized placebo controlled trial done at six university centers involving 200 patients for nearly one year. The dosage they used (100 mg twice daily) was much higher and likely less effective than what most clinicians currently use.

They also did not employ any additional antibiotics or nutritional regimens, yet 55 percent of patients improved. This study finally provided the "proof" that many traditional clinicians demanded before seriously considering this treatment as an alternative regimen for rheumatoid arthritis.

Dr. Thomas Brown's effort to treat the chronic mycoplasma infections believed to cause rheumatoid arthritis is the basis for this therapy. Dr. Brown believed that most rheumatic illnesses respond to this treatment. He and others used this therapy for SLE, ankylosing spondylitis, scleroderma, dermatomyositis and polymyositis.

Dr. Osler was one of the most well respected and prominent physicians of his time (1849- 1919), and many regard him as the consummate physician of modern times. An excerpt from a commentary on Dr. William Osler provides a useful perspective on application of alternative medical paradigms:

Osler would caution us against the arrogance of believing that only our current medical practices can benefit the patient. He would realize that new scientific insights might emerge from as yet unproved beliefs. Although he would fight vigorously to protect the public against frauds and charlatans, he would encourage critical study of whatever therapeutic approaches were reliably reported to be beneficial to patients.

Factors Associated with Your Success on this Program

There are many variables associated with an increased chance of remission or improvement.

- The younger you are, the greater your chance for improvement

- The more closely you follow the nutrition plan, the more likely you are to improve and the less likely you are to have a severe flare-up. I now offer the Nutritional Typing Test for free, so please do not skip this essential step.

- Smoking seems to be negatively associated with improvement

- The longer you have had the illness and the more severe the illness, the more difficult it seems to treat

Revised Antibiotic-Free Approach

Although I used a revision of his antibiotic approach for nearly ten years, my particular prejudice is to focus on natural therapies. The program that follows is my revision of this protocol that allows for a completely drug-free treatment of RA, which is based on my experience of treating over 3000 patients with rheumatic illnesses in my Chicago clinic.

If you are interested in reviewing or considering Dr. Brown's antibiotic approach, I have included a summary of his work and the evidence for it in the appendix.

Crucial Lifestyle Changes

Improving your diet using a combination of my nutritional guidelines, nutritional typing is crucial for your success. In addition, there are some general principles that seem to hold true for all nutritional types and these include:

- Eliminating sugar, especially fructose, and most grains. For most people it would be best to limit fruit to small quantities

- Eating unprocessed, high-quality foods, organic and locally grown if possible

- Eating your food as close to raw as possible

- Getting plenty high-quality animal-based omega-3 fats. Krill oil seems to be particularly helpful here as it appears to be a more effective anti inflammatory preparation. It is particularly effective if taken concurrently with 4 mg of Astaxanthin, which is a potent antioxidant bioflavanoid derived from algae

- Astaxanthin at 4 mg per day is particularly important for anyone placed on prednisone as Astaxanthin offers potent protection against cataracts and age related macular degeneration

- Incorporating regular exercise into your daily schedule

Early Emotional Traumas are Pervasive in Those with RA

With the vast majority of the patients I treated, some type of emotional trauma occurred early in their life, before the age their conscious mind was formed, which is typically around the age of 5 or 6. However, a trauma can occur at any age, and has a profoundly negative impact.

If that specific emotional insult is not addressed with an effective treatment modality then the underlying emotional trigger will continue to fester, allowing the destructive process to proceed, which can predispose you to severe autoimmune diseases like RA later in life.

In some cases, RA appears to be caused by an infection, and it is my experience that this infection is usually acquired when you have a stressful event that causes a disruption in your bioelectrical circuits, which then impairs your immune system.

This early emotional trauma predisposes you to developing the initial infection, and also contributes to your relative inability to effectively defeat the infection.

Therefore, it's very important to have an effective tool to address these underlying emotional traumas. In my practice, the most common form of treatment used is called the Emotional Freedom Technique (EFT).

Although EFT is something that you can learn to do yourself in the comfort of your own home, it is important to consult a well-trained professional to obtain the skills necessary to promote proper healing using this amazing tool.

Vitamin D Deficiency Rampant in Those with RA

The early part of the 21st century brought enormous attention to the importance and value of vitamin D, particularly in the treatment of autoimmune diseases like RA.

From my perspective, it is now virtually criminal negligent malpractice to treat a person with RA and not aggressively monitor their vitamin D levels to confirm that they are in a therapeutic range of 65-80 ng/ml.

This is so important that blood tests need to be done every two weeks, so the dose can be adjusted to get into that range. Most normal-weight adults should start at 10,000 units of vitamin D per day.

If you are in the US, then Lab Corp is the lab of choice as Quest labs provide results that are falsely elevated. If you choose to use Quest you need to multiply your result by 0.70 to obtain the right number.

For more detailed information on vitamin D you can review my vitamin D resource page.

Low Dose Naltrexone

One new addition to the protocol is low-dose Naltrexone, which I would encourage anyone with RA to try. It is inexpensive and non-toxic and I have a number of physician reports documenting incredible efficacy in getting people off of all their dangerous arthritis meds.

Although this is a drug, and strictly speaking not a natural therapy, it has provided important relief and is FAR safer than the toxic drugs that are typically used by nearly all rheumatologists.

Nutritional Considerations

Limiting sugar is a critical element of the treatment program. Sugar has multiple significant negative influences on your biochemistry. First and foremost, it increases your insulin levels, which is the root cause of nearly all chronic disease. It can also impair your gut bacteria.

In my experience if you are unable to decrease your sugar intake, you are far less likely to improve. Please understand that the number one source of calories in the US is high fructose corn syrup from drinking soda. One of the first steps you can take is to phase out all soda, and replace it with pure, clean water.

Exercise for Rheumatoid Arthritis

It is very important to exercise and increase muscle tone of your non-weight bearing joints. Experts tell us that disuse results in muscle atrophy and weakness. Additionally, immobility may result in joint contractures and loss of range of motion (ROM). Active ROM exercises are preferred to passive.

There is some evidence that passive ROM exercises increase the number of white blood cells (WBCs) in your joints.

If your joints are stiff, you should stretch and apply heat before exercising. If your joints are swollen, application of ten minutes of ice before exercise would be helpful.

The inflamed joint is very vulnerable to damage from improper exercise, so you must be cautious. People with arthritis must strike a delicate balance between rest and activity, and must avoid activities that aggravate joint pain. You should avoid any exercise that strains a significantly unstable joint.

A good rule of thumb is that if the pain lasts longer than one hour after stopping exercise, you should slow down or choose another form of exercise. Assistive devices are also helpful to decrease the pressure on affected joints. Many patients need to be urged to take advantage of these. The Arthritis Foundation has a book, Guide to Independent Living, which instructs patients about how to obtain them.

Of course, it is important to maintain good cardiovascular fitness as well. Walking with appropriate supportive shoes is another important consideration.

If your condition allows, it would be wise to move towards a Peak Fitness program that is designed for reaching optimal health.

It's Important to Control Your Pain

One of the primary problems with RA is controlling pain. The conventional treatment typically includes using very dangerous drugs like prednisone, methotrexate, and drugs that interfere with tumor necrosis factor, like Enbrel.

The goal is to implement the lifestyle changes discussed above as quickly as possible, so you can start to reduce these toxic and dangerous drugs, which do absolutely nothing to treat the cause of the disease.

However pain relief is obviously very important, and if this is not achieved, you can go into a depressive cycle that can clearly worsen your immune system and cause the RA to flare.

So the goal is to be as comfortable and pain free as possible with the least amount of drugs. The Mayo Clinic offers several common sense guidelines for avoiding pain by paying heed to how you move, so as to not injure your joints.

Safest Anti-Inflammatories to Use for Pain

Clearly the safest prescription drugs to use for pain are the non-acetylated salicylates such as:

- Salsalate

- Sodium salicylate

- Magnesium salicylate (i.e., Salflex, Disalcid, or Trilisate).

They are the drugs of choice if there is renal insufficiency as they minimally interfere with anticyclooxygenase and other prostaglandins.

Additionally, they will not impair platelet inhibition in those patients who are on an every-other-day aspirin regimen to decrease their risk for stroke or heart disease.

Unlike aspirin, they do not increase the formation of products of lipoxygenase-mediated metabolism of arachidonic acid. For this reason, they may be less likely to cause hypersensitivity reactions. These drugs have been safely used in patients with reversible obstructive airway disease and a history of aspirin sensitivity.

They are also much gentler on your stomach than the other NSAIDs and are the drug of choice if you have problems with peptic ulcer disease. Unfortunately, all these benefits are balanced by the fact they may not be as effective as the other agents and are less convenient to take. You need to take 1.5-2 grams twice a day, and tinnitus, or ringing in your ear, is a frequent side effect.

You need to be aware of this complication and know that if tinnitus does develop, you need to stop the drugs for a day and restart with a dose that is half a pill per day lower. You can repeat this until you find a dose that relieves your pain and doesn't cause any ringing in your ears.

If the Safer Anti-Inflammatories aren't Helping, Try This Next…

If the non-acetylated salicylates aren't helping there are many different NSAIDs to try. Relafen, Daypro, Voltaren, Motrin, Naprosyn. Meclomen, Indocin, Orudis, and Tolectin are among the most toxic or likely to cause complications. You can experiment with them, and see which one works best for you.

If cost is a concern, generic ibuprofen can be used at up to 800 mg per dose. Unfortunately, recent studies suggest this drug is more damaging to your kidneys.

If you use any of the above drugs, though, it is really important to make sure you take them with your largest meal as this will somewhat moderate their GI toxicity and the likelihood of causing an ulcer.

Please beware that they are much more dangerous than the antibiotics or non-acetylated salicylates.

You should have an SMA blood test performed at least once a year if you are on these medications. In addition, you must monitor your serum potassium levels if you are on an ACE inhibitor as these medications can cause high potassium levels. You should also monitor your kidney function. The SMA will show any liver impairment the drugs might be causing.

These medications can also impair prostaglandin metabolism and cause papillary necrosis and chronic interstitial nephritis. Your kidney needs vasodilatory prostaglandins (PGE2 and prostacycline) to counterbalance the effects of potent vasoconstrictor hormones such as angiotensin II and catecholamines. NSAIDs decrease prostaglandin synthesis by inhibiting cyclooxygenase, leading to unopposed constriction of the renal arterioles supplying your kidney.

Warning: These Drugs Massively Increase Your Risk for Ulcers

The first non-aspirin NSAID, indomethacin, was introduced in 1963. Now more than 30 are available. Relafen is one of the better alternatives as it seems to cause less of an intestinal dysbiosis. You must be especially careful to monitor renal function periodically. It is important to understand and accept the risks associated with these more toxic drugs.

Every year, they do enough damage to the GI tract to kill 2,000 to 4,000 people with rheumatoid arthritis alone. That is ten people EVERY DAY. At any given time, 10 to 20 percent of all those receiving NSAID therapy have gastric ulcers.

If you are taking an NSAID, you are at approximately three times greater risk for developing serious gastrointestinal side effects than those who don't.

Approximately 1.2 percent of patients taking NSAIDs are hospitalized for upper GI problems, per year of exposure. One study of patients taking NSAIDs showed that a life-threatening complication was the first sign of ulcer in more than half of the subjects.

Researchers found that the drugs suppress production of prostacyclin, which is needed to dilate blood vessels and inhibit clotting. Earlier studies had found that mice genetically engineered to be unable to use prostacyclin properly were prone to clotting disorders.

Anyone who is at increased risk of cardiovascular disease should steer clear of these medications. Ulcer complications are certainly potentially life-threatening, but, heart attacks are a much more common and likely risk, especially in older individuals.

How You Can Tell if You are at Risk for NSAID Side Effects

Risk factor analysis can help determine if you will face an increased danger of developing these complications. If you have any of the following, you will likely to have a higher risk of side effects from these drugs:

- Old age

- Peptic ulcer history

- Alcohol dependency

- Cigarette smoking

- Concurrent prednisone or corticosteroid use

- Disability

- Taking a high dose of the NSAID

- Using an NSAID known to be more toxic

Prednisone

The above drug class are called non steroidal anti inflammatories (NSAIDs). If they are unable to control the pain, then prednisone is nearly universally used. This is a steroid drug that is loaded with side effects.

If you are on large doses of prednisone for extended periods of time, you can be virtually assured that you will develop the following problems:

- Osteoporosis

- Cataracts

- Diabetes

- Ulcers

- Herpes reactivation

- Insomnia

- Hypertension

- Kidney stones

You can be virtually assured that every time you take a dose of prednisone your bones are becoming weaker. The higher the dose and the longer you are on prednisone, the more likely you are to develop the problems.

However, if you are able to keep your dose to 5 mg or below, this is not typically a major issue.

Typically this is one of the first medicines you should try to stop as soon as your symptoms permit.

Beware that blood levels of cortisol peak between 3 and 9am. It would, therefore, be safest to administer the prednisone in the morning. This will minimize the suppression on your hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.

You also need to be concerned about the increased risk of peptic ulcer disease when using this medicine with conventional non-steroidal anti-inflammatories. If you are taking both of these medicines, you have a 15 times greater risk of developing an ulcer!

If you are already on prednisone, it is helpful to get a prescription for 1 mg tablets so you can wean yourself off the prednisone as soon as possible. Usually you can lower your dose by about 1 mg per week. If a relapse of your symptoms occurs, then further reduction of the prednisone is not indicated.

How Do You Know When to Stop the Drugs?

Unlike conventional approaches to RA, my protocol is designed to treat the underlying cause of the problem. So eventually the drugs that you are going to use during the program will be weaned off.

The following criteria can help determine when you are in remission and can consider weaning off your medications: *

- A decrease in duration of morning stiffness to no more than 15 minutes

- No pain at rest

- Little or no pain or tenderness on motion

- Absence of joint swelling

- A normal energy level

- A decrease in your ESR to no more than 30

- A normalization of your CBC. Generally your HGB, HCT, & MCV will increase to normal and your "pseudo"-iron deficiency will disappear

- ANA, RF, & ASO titers returning to normal

If you discontinue your medications before all of the above criteria are met, there is a greater risk that the disease will recur.

If you meet the above criteria, you can try to wean off your anti-inflammatory medication and monitor for flare-ups. If no flare-ups occur for six months, then discontinue the clindamycin.

If the improvements are maintained for the next six months, you can then discontinue your Minocin and monitor for recurrences. If symptoms should recur, it would be wise to restart the previous antibiotic regimen.

Evaluation to Determine and Follow RA

If you have received evaluations and treatment by one or more board certified rheumatologists, you can be very confident that the appropriate evaluation was done. Although conventional treatments fail miserably in the long run, the conventional diagnostic approach is typically excellent, and you can start the treatment program discussed above.

If you have not been evaluated by a specialist then it will be important to be properly evaluated to determine if indeed you have rheumatoid arthritis.

Please be sure and carefully review Appendix Two, as you will want to confirm that fibromyalgia is not present.

Beware that arthritic pain can be an early manifestation of 20-30 different clinical problems.

These include not only rheumatic disease, but also metabolic, infectious and malignant disorders. Rheumatoid arthritis is a clinical diagnosis for which there is not a single test or group of laboratory tests which can be considered confirmatory.

Criteria for Classification of Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Morning Stiffness - Morning stiffness in and around joints lasting at least one hour before maximal improvement is noted.

- Arthritis of three or more joint areas - At least three joint areas have simultaneously had soft-tissue swelling or fluid (not bony overgrowth) observed by a physician. There are 14 possible joints: right or left PIP, MCP, wrist, elbow, knee, ankle, and MTP joints.

- Arthritis of hand joints - At least one joint area swollen as above in a wrist, MCP, or PIP joint.

- Symmetric arthritis - Simultaneous involvement of the same joint areas (as in criterion 2) on both sides of your body (bilateral involvement of PIPs, MCPs, or MTPs) is acceptable without absolute symmetry. Lack of symmetry is not sufficient to rule out the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis.

- Rheumatoid Nodules - Subcutaneous nodules over bony prominences, or extensor surfaces, or in juxta-articular regions, observed by a physician. Only about 25 percent of patients with rheumatoid arthritis develop nodules, and usually as a later manifestation.

- Serum Rheumatoid Factor - Demonstration of abnormal amounts of serum rheumatoid factor by any method that has been positive in less than 5 percent of normal control subjects. This test is positive only 30-40 percent of the time in the early months of rheumatoid arthritis.

You must also make certain that the first four symptoms listed in the table above are present for six or more weeks. These criteria have a 91-94 percent sensitivity and 89 percent specificity for the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis.

However, these criteria were designed for classification and not for diagnosis. The diagnosis must be made on clinical grounds. It is important to note that many patients with negative serologic tests can have a strong clinical picture for rheumatoid arthritis.

Your Hands are the KEY to the Diagnosis of RA

In a way, the hands are the calling card of rheumatoid arthritis. If you completely lack hand and wrist involvement, even by history, the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis is doubtful. Rheumatoid arthritis rarely affects your hips and ankles early in its course.

The metacarpophalangeal joints, proximal interphalangeal and wrist joints are the first joints to become symptomatic. Osteoarthritis typically affects the joints that are closest to your fingertips (DIP joints) while RA typically affects the joints closest to your wrist (PIP), like your knuckles.

Fatigue may be present before your joint symptoms begin, and morning stiffness is a sensitive indicator of rheumatoid arthritis. An increase in fluid in and around your joint probably causes the stiffness. Your joints are warm, but your skin is rarely red.

When your joints develop effusions, hold them flexed at 5 to 20 degrees as it is likely going to be too painful to extend them fully.

Radiological Changes

Radiological changes typical of rheumatoid arthritis on PA hand and wrist X-rays, which must include erosions or unequivocal bony decalcification localized to, or most marked, adjacent to the involved joints (osteoarthritic changes alone do not count).

Note: You must satisfy at least four of the seven criteria listed. Any of criteria 1-4 must have been present for at least 6 weeks. Patients with two clinical diagnoses are not excluded. Designations as classic, definite, or probable rheumatoid arthritis, are not to be made.

Laboratory Evaluation

The general initial laboratory evaluation should include a baseline ESR, CBC, SMA, U/A, 25 hydroxy D level and an ASO titer. You can also draw RF and ANA titers to further objectively document improvement with the therapy. However, they seldom add much to the assessment.

Follow-up visits can be every two to four months depending on the extent of the disease and ease of testing.

The exception here would be vitamin D testing which should be done every two weeks until your 25 hydroxy D level is between 65 and 80 ng/ml.

Many patients with rheumatoid arthritis have a hypochromic, microcytic CBC that appears very similar to iron deficiency, but it is not at all related. This is probably due to the inflammation in the rheumatoid arthritis impairing optimal bone marrow utilization of iron.

It is important to note that this type of anemia does NOT respond to iron and if you are put on iron you will get worse, as the iron is a very potent oxidative stress. Ferritin levels are generally the most reliable indicator of total iron body stores. Unfortunately it is also an acute phase reactant protein and will be elevated anytime the ESR is elevated. This makes ferritin an unreliable test in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

APPENDIX ONE: The Infectious Cause of Rheumatoid Arthritis

It is quite clear that autoimmunity plays a major role in the progression of rheumatoid arthritis. Most rheumatology investigators believe that an infectious agent causes rheumatoid arthritis. There is little agreement as to the involved organism, however.

Investigators have proposed the following infectious agents:

- Human T-cell lymphotropic virus Type I

- Rubella virus

- Cytomegalovirus

- Herpesvirus

- Mycoplasma

This review will focus on the evidence supporting the hypothesis that mycoplasma is a common etiologic agent of rheumatoid arthritis.

Mycoplasmas are the smallest self-replicating prokaryotes. They differ from classical bacteria by lacking rigid cell wall structures and are the smallest known organisms capable of extracellular existence. They are considered to be parasites of humans, animals, and plants.

Culturing Mycoplasmas from Joints

Mycoplasmas have limited biosynthetic capabilities and are very difficult to culture and grow from synovial tissues. They require complex growth media or a close parasitic relation with animal cells. This contributed to many investigators failure to isolate them from arthritic tissue.

In reactive arthritis, immune complexes rather than viable organisms localize in your joints. The infectious agent is actually present at another site. Some investigators believe that the organism binding in the immune complex contributes to the difficulty in obtaining positive mycoplasma cultures.

Despite this difficulty, some researchers have successfully isolated mycoplasma from synovial tissues of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. A British group used a leucocyte-migration inhibition test and found two-thirds of their rheumatoid arthritis patients to be infected with Mycoplasma fermentens. These results are impressive since they did not include more prevalent Mycoplasma strains like M salivarium, M ovale, M hominis, and M pneumonia.

One Finnish investigator reported a 100 percent incidence of isolation of mycoplasma from 27 rheumatoid synovia using a modified culture technique. None of the non- rheumatoid tissue yielded any mycoplasmas.

The same investigator used an indirect hemagglutination technique and reported mycoplasma antibodies in 53 percent of patients with definite rheumatoid arthritis. Using similar techniques other investigators have cultured mycoplasma in 80-100 percent of their rheumatoid arthritis test population.

Rheumatoid arthritis can also follow some mycoplasma respiratory infections.

One study of over 1000 patients was able to identify arthritis in nearly 1 percent of the patients. These infections can be associated with a positive rheumatoid factor. This provides additional support for mycoplasma as an etiologic agent for rheumatoid arthritis. Human genital mycoplasma infections have also caused septic arthritis.

Harvard investigators were able to culture mycoplasma or a similar organism, ureaplasma urealyticum, from 63 percent of female patients with SLE and only 4 percent of patients with CFS. The researchers chose CFS, as these patients shared similar symptoms as those with SLE, such as fatigue, arthralgias, and myalgias.

Animal Evidence for the Protocol

The full spectrum of human rheumatoid arthritis immune responses (lymphokine production, altered lymphocyte reactivity, immune complex deposition, cell-mediated immunity and development of autoimmune reactions) occurs in mycoplasma induced animal arthritis.

Investigators have implicated at least 31 different mycoplasma species.

Mycoplasma can produce experimental arthritis in animals from three days to months later. The time seems to depend on the dose given, and the virulence of the organism.

There is a close degree of similarity between these infections and those of human rheumatoid arthritis.

Mycoplasmas cause arthritis in animals by several mechanisms. They either directly multiply within the joint or initiate an intense local immune response.

Arthritogenic mycoplasmas also cause joint inflammation in animals by several mechanisms. They induce nonspecific lymphocyte cytotoxicity and antilymphocyte antibodies as well as rheumatoid factor.

Mycoplasma clearly causes chronic arthritis in mice, rats, fowl, swine, sheep, goats, cattle and rabbits. The arthritis appears to be the direct result of joint infection with culturable mycoplasma organisms.

Gorillas have tissue reactions closer to man than any other animal, and investigators have shown that mycoplasma can precipitate a rheumatic illness in gorillas. One study demonstrated that mycoplasma antigens do occur in immune complexes in great apes.

The human and gorilla IgG are very similar and express nearly identical rheumatoid factors (IgM anti-IgG antibodies). The study showed that when mycoplasma binds to IgG it can cause a conformational change. This conformational change results in an anti-IgG antibody, which can then stimulate an autoimmune response.

The Science of Why Minocycline is Used

If mycoplasma were a causative factor in rheumatoid arthritis, one would expect tetracycline type drugs to provide some sort of improvement in the disease. Collagenase activity increases in rheumatoid arthritis and probably has a role in its cause.

Investigators have demonstrated that tetracycline and minocycline inhibit leukocyte, macrophage, and synovial collagenase.

There are several other aspects of tetracyclines that may play a role in rheumatoid arthritis. Investigators have shown minocycline and tetracycline to retard excessive connective tissue breakdown and bone resorption, while doxycycline inhibits digestion of human cartilage.

It is also possible that tetracycline treatment improves rheumatic illness by reducing delayed-type hypersensitivity response. Minocycline and doxycycline both inhibit phosolipases which are considered proinflammatory and capable of inducing synovitis.

Minocycline is a more potent antibiotic than tetracycline and penetrates tissues better.

These characteristics shifted the treatment of rheumatic illness away from tetracycline to minocycline. Minocycline may benefit rheumatoid arthritis patients through its immunomodulating and immunosuppressive properties. In vitro studies have demonstrated a decreased neutrophil production of reactive oxygen intermediates along with diminished neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytosis.

Minocycline has also been shown to reduce the incidence and severity of synovitis in animal models of arthritis. The improvement was independent of minocycline's effect on collagenase. Minocycline has also been shown to increase intracellular calcium concentrations that inhibit T-cells.

Individuals with the Class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC) DR4 allele seem to be predisposed to developing rheumatoid arthritis.

The infectious agent probably interacts with this specific antigen in some way to precipitate rheumatoid arthritis. There is strong support for the role of T cells in this interaction.

So minocycline may suppress rheumatoid arthritis by altering T cell calcium flux and the expression of T cell derived from collagen binding protein. Minocycline produced a suppression of the delayed hypersensitivity in patients with Reiter's syndrome, and investigators also successfully used minocycline to treat the arthritis and early morning stiffness of Reiter's syndrome.

Clinical Studies

In 1970, investigators at Boston University conducted a small, randomized placebo-controlled trial to determine if tetracycline would treat rheumatoid arthritis. They used 250 mg of tetracycline a day.

Their study showed no improvement after one year of tetracycline treatment. Several factors could explain their inability to demonstrate any benefits.

Their study used only 27 patients for a one-year trial, and only 12 received tetracycline, so noncompliance may have been a factor. Additionally, none of the patients had severe arthritis. Patients were excluded from the trial if they were on any anti-remittive therapy.

Finnish investigators used lymecycline to treat the reactive arthritis in Chlamydia trachomatous infections. Their study compared the effect of the medication in patients with two other reactive arthritis infections: Yersinia and Campylobacter.

Lymecyline produced a shorter course of illness in the Chlamydia induced arthritis patients, but did not affect the other enteric infections-associated reactive arthritis. The investigators later published findings that suggested lymecycline achieved its effect through non-antimicrobial actions. They speculated it worked by preventing the oxidative activation of collagenase.

The first trial of minocycline for the treatment of animal and human rheumatoid arthritis was published by Breedveld. In the first published human trial, Breedveld treated ten patients in an open study for 16 weeks. He used a very high dose of 400 mg per day. Most patients had vestibular side effects resulting from this dose.

However, all patients showed benefit from the treatment, and all variables of efficacy were significantly improved at the end of the trial.

Breedveld expanded on his initial study and later observed similar impressive results. This was a 26-week double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trial with minocycline for 80 patients. They were given 200 mg twice a day.

The Ritchie articular index and the number of swollen joints significantly improved (p < 0.05) more in the minocyline group than in the placebo group.

Investigators in Israel studied 18 patients with severe rheumatoid arthritis for 48 weeks.

These patients had failed two other DMARD. They were taken off all DMARD agents and given minocycline 100 mg twice a day. Six patients did not complete the study -- three withdrew because of lack of improvement, and three had side effects of vertigo or leukopenia.

All patients completing the study improved. Three had complete remission, three had substantial improvement of greater than 50 percent, and six had moderate improvement of 25 percent in the number of active joints and morning stiffness.

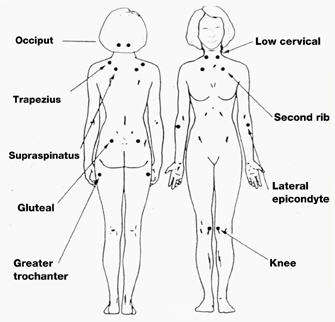

APPENDIX TWO: Make Certain You are Assessed for Fibromyalgia

You need to be very sensitive to this condition when you have rheumatoid arthritis as it is frequently a complicating condition. Many times, the pain will be confused with a flare-up of the RA.

You need to aggressively treat this problem. If it is ignored, the likelihood of successfully treating the arthritis is significantly diminished.

Fibromyalgia is a very common problem. Some experts believe that 5 percent of people are affected with it. Over 12 percent of the patients at the Mayo Clinic's Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation have this problem, and it is the third most common diagnosis by rheumatologists in the outpatient setting. Fibromyalgia affects women five times as frequently as men.

Signs and Symptoms of Fibromyalgia

One of the main features of fibromyalgia is morning stiffness, fatigue, and multiple areas of tenderness in typical locations. Most people with fibromyalgia complain of pain over many areas of their body, with an average of six to nine locations. Although the pain is frequently described as being "all over," it is most prominent in the neck, shoulders, elbows, hips, knees, and back.

Tender points are generally symmetrical and on both sides of the body. The areas of tenderness are usually small (less than an inch in diameter) and deep within the muscle. They are often located in sites that are slightly tender in normal people.

People with fibromyalgia, however, differ in having increased tenderness at these sites than the average person. Firm palpation with the thumb (just past the point where the nail turns white) over the outside elbow will typically cause a vague sensation of discomfort. Patients with fibromyalgia will experience much more pain and will often withdraw the arm involuntarily.

More than 70 percent of patients describe their pain as profound aching and stiffness of muscles. Often it is relatively constant from moment to moment, but certain positions or movements may momentarily worsen the pain. Other terms used to describe the pain are "dull" and "numb."

Sharp or intermittent pain is relatively uncommon.

Patients with fibromyalgia also often complain that sudden loud noises worsen their pain.

The generalized stiffness of fibromyalgia does not diminish with activity, unlike the stiffness of rheumatoid arthritis, which lessens as the day progresses. Despite the lack of abnormal lab tests, patients can suffer considerable discomfort.

The fatigue is often severe enough to impair activities of work and recreation. Patients commonly experience fatigue on arising and complain of being more fatigued when they wake up than when they went to bed.

Over 90 percent of patients believe the pain, stiffness, and fatigue are made worse by cold, damp weather. Overexertion, anxiety and stress are also factors.

Many find that localized heat, such as hot baths, showers, or heating pads, give them some relief. There is also a tendency for pain to improve in the summer with mild activity, or with rest.

Some patients will date the onset of their symptoms to some initiating event. This is often an injury, such as a fall, a motor vehicle accident, or a vocational or sports injury. Others find that their symptoms began with a stressful or emotional event, such as a death in the family, a divorce, a job loss, or similar occurrence.

Pain Location

Patients with fibromyalgia have pain in at least 11 of the following 18 tender point sites (one on each side of the body):

- Base of the skull where the suboccipital muscle inserts.

- Back of the low neck (anterior intertransverse spaces of C5-C7).

- Midpoint of the upper shoulders (trapezius).

- On the back in the middle of the scapula.

- On the chest where the second rib attaches to the breastbone (sternum).

- One inch below the outside of each elbow (lateral epicondyle).

- Upper outer quadrant of buttocks.

- Just behind the swelling on the upper leg bone below the hip (trochanteric prominence).

- The inside of both knees (medial fat pads proximal to the joint line).

Treatment of Fibromyalgia

There is a persuasive body of emerging evidence that indicates that patients with fibromyalgia are physically unfit in terms of sustained endurance. Some studies show that exercise can decrease fibromyalgia pain by 75 percent.

Sleep is also critical to improvement, and many times, improved fitness will also correct the sleep disturbance.

Normalizing vitamin D levels has also been shown to be helpful to decrease pain as has topical magnesium oil supplementation.

Allergies, especially to mold, seem to be another common cause of fibromyalgia. There are some simple interventions using techniques called Total Body Modification (TBM) 800-243-4826.

APPENDIX THREE: Antibiotic Therapy with Minocin

There are three different tetracyclines available: simple tetracycline, doxycycline, or Minocin (minocycline).

Minocin has a distinct and clear advantage over tetracycline and doxycycline in three important areas:

- Extended spectrum of activity

- Greater tissue penetrability

- Higher and more sustained serum levels

Bacterial cell membranes contain a lipid layer. One mechanism of building up a resistance to an antibiotic is to produce a thicker lipid layer. This layer makes it difficult for an antibiotic to penetrate. Minocin's chemical structure makes it the most lipid soluble of all the tetracyclines.

This difference can clearly be demonstrated when you compare the drugs in the treatment of two common clinical conditions.

Minocin gives consistently superior clinical results in the treatment of chronic prostatitis. In other studies, Minocin was used to improve between 75-85 percent of patients whose acne had become resistant to tetracycline. Strep is also believed to be a contributing cause to many patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Minocin has shown significant activity against treatment of this organism.

Important Factors to Consider When Using Minocin

Unlike the other tetracyclines, Minocin tends not to cause yeast infections. Some infectious disease experts even believe that it has a mild anti-yeast activity. Women can be on this medication for several years and not have any vaginal yeast infections. Nevertheless, it would be prudent to take prophylactic oral lactobacillus acidophilus and bifidus preparations.

This will help to replace the normal intestinal flora that is killed with the Minocin.

Another advantage of Minocin is that it tends not to sensitize you to the sun. This minimizes your risk of sunburn and increased risk of skin cancer.

However, you must incorporate several precautions with the use of Minocin.

Like other tetracyclines, food impairs its absorption. However, the absorption is much less impaired than with other tetracyclines. This is fortunate because some people cannot tolerate Minocin on an empty stomach and have to take it with a meal to avoid GI side effects.

If you need to take it with a meal, you will still absorb 85 percent of the medication, whereas tetracycline is only 50 percent absorbed. In June of 1990, a pelletized version of Minocin also became available, which improved absorption when taken with meals.

This form is only available in the non-generic Lederle brand, and is a more than reasonable justification to not substitute for the generic version.

Clinical experience has shown that many patients will relapse when they switch from the brand name to the generic. In February, 2006 Wyeth sold manufacturing rights of Minocin to Triax Pharmaceuticals (866-488-7429).

Clinically, it has been documented that it is important to take Lederle brand Minocin as most all generic minocycline are clearly less effective.

A large percentage of patients will not respond at all, or not do as well with generic non-Lederle minocycline.

Traditionally it was recommended to only receive the brand name Lederle Minocin. However, there is one generic brand that is acceptable, and that is the brand made by Lederle. The only difference between Lederle generic Minocin and brand name Minocin is the label and the price.

The problem is finding the Lederle brand generic. Some of my patients have been able to find it at Wal Mart. Since Wal Mart is one of the largest drug chains in the US, this should make the treatment more widely available for a reduced charge.

Many patients are on NSAID's that contribute to microulcerations of the stomach, which cause chronic blood loss. It is certainly possible to develop a peptic ulcer contributing to this blood loss. In either event, patients are frequently receiving iron supplements to correct their blood counts.

IT IS IMPERATIVE THAT MINOCIN NOT BE GIVEN WITH IRON!

Over 85 percent of the dose will bind to the iron and pass through your colon unabsorbed.

If iron is taken, it should be at least one hour before Minocin, or two hours after.

A recent, uncommon, complication of Minocin is a cell-mediated hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

Most patients can start on 100 mg of Minocin every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday evening. Doxycycline can be substituted for patients who cannot afford the more expensive Minocin.

It is important to not give either medication daily, as this does not seem to provide as great a clinical benefit.

WARNING: Tetracycline type drugs can cause a permanent yellow- grayish brown discoloration of your teeth.

This can occur in the last half of pregnancy, and in children up to eight years old. You should not routinely use tetracycline in children.

If you have severe disease, you can consider increasing the dose to as high as 200 mg three times a week. Aside from the cost of this approach, several problems may result from the higher doses.

Minocin can cause quite severe nausea and vertigo, but taking the dose at night tends to decrease this problem considerably.

However, if you take the dose at bedtime, you must swallow the medication with TWO glasses of water. This is to insure that the capsule doesn't get stuck in your throat. If that occurs, a severe chemical esophagitis can result, which can send you to the emergency room.

For those physicians who elect to use tetracycline or doxycycline for cost or sensitivity reasons, several methods may help lessen the inevitable secondary yeast overgrowth. Lactobacillus acidophilus will help maintain normal bowel flora and decrease the risk of fungal overgrowth.

Aggressive avoidance of all sugars, especially those found in non-diet sodas will also decrease the substrate for the yeast's growth. Macrolide antibiotics like Biaxin or Zithromax may be used if tetracyclines are contraindicated.

They would also be used in the three pills a week regimen.

Clindamycin

The other drug used to treat rheumatoid arthritis is clindamycin. Dr. Brown's book discusses the uses of intravenous clindamycin, and it is important to use the IV form of treatment if the disease is severe.

In my experience nearly all scleroderma patients require a more aggressive stance and use IV treatment. Scleroderma is a particularly dangerous form of rheumatic illness that should receive aggressive intervention.

A major problem with the IV form is the cost. The price ranges from $100 to $300 per dose if administered by a home health care agency. However, if purchased directly from Upjohn, significant savings can be had.

If you have a milder illness, the oral form of clindamycin is preferable.

With a mild rheumatic illness (the minority of cases), it is even possible to exclude this from your regimen. Initial starting doses for an adult would be a 1200 mg dose once a week.

Please note that many people do not seem to tolerate this medication as well as Minocin. The major complaint seems to be a bitter metallic type taste, which lasts about 24 hours after the dose. Taking the dose after dinner does seem to help modify this complaint somewhat. If this is a problem, you can lower the dose and gradually increase the dose over a few weeks.

Concern about the development of C. difficile pseudomembranous enterocolitis as a result of the clindamycin is appropriate. This complication is quite rare at this dosage regimen, but it certainly can occur.

It is also important to be aware of the possibility of developing a severe and uncontrollable bout of diarrhea. Administration of acidophilus seems to limit this complication by promoting the growth of the healthy gut flora.

If you have a resistant form of rheumatic illness, intravenous administration should be considered. Generally, weekly doses of 900 mg are administered until clinical improvement is observed. This generally occurs within the first 10 doses.

At that time, the regimen can be decreased to every two weeks with the oral form substituted on the weeks where the IV is not taken.

What to Do if You Fail to Respond

The most frequent reason for failure to respond to the protocol is lack of adherence to the dietary guidelines.

Most people eat too many grains and sugars, which disturbs insulin physiology. It is important that you adhere as strictly as possible to the guidelines.

A small minority, generally under 15 percent of patients will fail to respond to the protocol described above, despite rigid adherence to the diet. These individuals should already be on the IV clindamycin.

It appears that hyaluronic acid, which is a potentiating agent commonly used in the treatment of cancer, may be quite useful in these cases. It seems that hyaluronic acid has very little to no direct toxicity but works in a highly synergistic fashion when administered directly in the IV bag with the clindamycin.

Hyaluronic acid is also used in orthopedic procedures. The dose is generally from 2 to 10 cc into the IV bag. Hyaluronic acid is not inexpensive, however, as the cost may range up to $10 per cc. You also need to use some caution, as it may precipitate a significant Herxheimer flare reaction.

Bibliography

- Pincus T, Wolfe F: Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis: Challenges to Traditional Paradigms. AnnInternMed 115:825-6, Nov 15 1991.

- Pincus T: Rheumatoid arthritis: disappointing long-term outcomes despite successful short-term clinical trials. J Clin Epidemiol 41:1037-41, 1988.

- Brooks PM: Clinical management of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 341 :286-90, 1993.

- Pincus T, Callahan LF: Remodeling the pyramid or remodeling the paradigms concerning rheumatoid arthritis - lessons learned from Hodgkin's Disease and coronary artery disease. JRheumatol 17:1582-5, 1990.

- Reah TG: The prognosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Proc R Soc Med 56:813-17, 1963.

- Wolfe F, Hawley DJ: Remission in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 12:245-9, 1985.

- Kushner I, Dawson NV: Changing perspectives in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. JRheumatol 19:1831-34, 1992.

- Pinals RS: Drug therapy in rheumatoid arthritis a perspective. Br J Rheumatol 28:93-5, 1989.

- Klippel JH: Winning the battle, losing the war? Another editorial about rheumatoid arthritis. JRheumatol 17:1118-22. 1990.

- Healey LA, Wilske KR: Evaluating combination drug therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 18:641-2, 1991.

- Wolfe F: 50 Years of antirheumatic therapy: the prognosis of rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 17:24-32, 1990.

- Gabriel SE, Luthra HS: Rheumatoid arthritis: Can the long term be altered? Mayo Clin Proc 63:58-68, 1988.

- Harris ED: Rheumatoid arthritis: Pathophysiology and implications for therapy. NEngl JMed 322:1277-1289, May 3, 1990.

- Schwartz BD: Infectious agents, immunity and rheumatic diseases. Arthr Rheum 33 :457-465, April 1990.

- Tan PLJ, Skinner MA: The microbial cause of rheumatoid arthritis: time to dump Koch's postulates. J Rheumatol 19:1170-71. 1992.

- Ford DK: The microbiological causes of rheumatoid arthritis. JRheumatol 18:1441-2, 1991.

- Burmester GR: Hit and run or permanent hit? Is there evidence for a microbiological cause of rheumatoid arthritis? J Rheumatol 18:1443-7, 1991.

- Phillips PE: Evidence implications infectious agents in rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Clin EXD Rheumatol 1988 6:87-94.

- Sabin AB: Experimental proliferative arthritis in mice produced by filtrable pleuropneumonia-like microorganisms. Science 89:228-29, 1939.

- Swift HF, Brown TMcP: Pathogenic pleuropneumonia-like organisms from acute rheumatic exudates and tissues. Science 89:271-272. 1939.

- Clark HW, Bailey JS, Brown TMcP: Determination of mycoplasma antibodies in humans. Bacteriol Proc 64:59, 1964.

- Brown Tmcp, Wichelausen RH, Robinson LB, et al: The in vivo action of aureomycin on pleuropneumonia-like organisms associated with various rheumatic diseases. J Lab Clin Med 34: 1404-1410. 1949.

- Brown TMcP, Wichelhausen RH: A study of the antigen-antibody mechanism in rheumatic diseases. Amer JMed Sci 221:618, 1951.

- Brown TMcP: The rheumatic crossroads. Postgrad Med 19:399-402, 1956.

- Brown TMcP, Clark HW, Bailey JS, et al: Relationship between mycoplasma antibodies and rheumatoid factors. ArthrRheum 13:309-310, 1970.

- Clark HW, Brown TMcP: Another look at mycoplasma. Arthr Rheum 19:649-50, 1976.

- Hakkarainen K, et al: Mycoplasmas and arthritis. Ann Rheumat Dis 51: S70-72; l992.

- Rook, GAW, et al: A reppraisal of the evidence that rheumatoid arthritis and several other idiopathic diseases are slow bacterial infections. Ann Rheum Dis 52:S30-S38; 1993.

- Clark HW, Coker-Vann MR, Bailey JS, et al: Detection of mycoplasma antigens in immune complexes from rheumatoid arthritis synovial fluids. Ann Allergy 60:394-98, May 1988.

- Wilder RL: Etiologic considerations in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Intern Med 101 :820-21, 1984.

- Bartholomew LE: Isolations and characterization of mycoplasmas (PPLO) from patients with rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus and Reiter's syndrome. Arthr Rheum 8:376-388. 1965.

- Brown TMcP, et al: Mycoplasma antibodies in synovia. Arthritis Rheum 9:495, 1966.

- Hernandez LA, Urquhart GED, *** WC: Mycoplasma pneumonia infection and arthritis in man. Br Med J 2: 14- 16. 1977.

- McDonald MI, Moore JO, Harrelson JM, et al: Septic arthritis due to Mycoplasma hominis. Arth Rheum 26: 1044-47, 1983.

- Williams MH, Brostoff J, Roitt IM: Possible role of Mycoplasma fermenters in pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2:277-280 1970

- Jansson E, Makisara P, Vainio K, et al: An 8-year study on mycoplasma in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 30:506-508, 1971.

- Jansson E, Makisara P, Tuuri S: Mycoplasma antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis. Scan J Rheumatol 4: 165-68, 1975.

- Markham JG, Myers DB: Preliminary observations on an isolate from synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis, S 1-7 1976.

- Tully JG, et al: Pathogenic mycoplasmas: cultivation and vertebrate pathogenicity of a new spiroplasma. Science 195:892-4, 1977.

- Fahlberg WJ, et al: Isolation of mycoplasma from human synovial fluids and tissues. Bacteria Proceedings 66:48-9, 1966.

- Ponka A: The occurrence and clinical picture of serologically verified Mycoplasma pneumonia infections with emphasis on central nervous system, cardiac and joint manifestations. Ann Clin Res II (suppl) 24, 1979.

- Hernandez LA, Urquhart GED, *** WC: Mycoplasma pneumonia infections and arthritis in man. Br Med J2:14-16, 1977.

- Ponka A: Arthritis associated with Mycoplasma pneumonia infection. Scand J Rheumatol 8:27-32, 1979.

- Stuckey M, Quinn PA, Gelfand EW: Identification of T-Strain mycoplasma in a patient with polyarthritis. Lancet 2:917-920. 1978.

- Webster ADB, Taylor-Robinson D, Furr PM, et al: Mycoplasmal septic arthritis in hypogammaglobuinemia. Br Med J 1 :478-79, 1978.

- Ginsburg KS, Kundsin RB, Walter CW, et al: Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatism 35 429-33, 1992.

- Cole BC, Cassel GH: Mycoplasma infections as models of chronic joint inflammation. Arthr Rheum 22:1375-1381, Dec 1979.

- Cassell GH, Cole BC: Mycoplasmas as agents of human disease. N Engl J Med 304: 80-89, Jan 8, 1981.

- Jansson E, et al: Mycoplasmas and arthritis. Rheumatol 42:315-9, 1983.

- Camon GW, Cole BCC, Ward JR, et al: Arthritogenic effects of Mycoplasma arthritides T cell mitogen in rats. JRheumatol 15:735-41, 1988.

- Cedillo L, Gil C, Mayagoita G, et al: Experimental arthritis induced by Mycoplasma pneumonia in rabbits. JRheumatol 19:344-7, 1992.

- Baccala R, Smith LR, Vestberg M, et al: Mycoplasma arthritidis mitogen. Arthritis Rheumatism 35:43442, 1992.

- Brown McP, Clark HW, Bailey JS: Rheumatoid arthritis in the gorilla: a study of mycoplasma-host interaction in pathogenesis and treatment. In Comparative Pathology of Zoo Animals, RJ Montali, Gigaki (ed), Smithsonian Institution Press. 1980. 259-266.

- Clark HW: The potential role of mycoplasmas as autoantigens and immune complexes in chronic vascular pathogenesis. Am J Primatol 24:235-243, 1991.

- Greenwald, rheumatoid arthritis, Goulb LM, Lavietes B, et al: Tetracyclines imibit human synovial collagenase in vivo and in vitro. RhPn fol 14:28-32. 1987.

- Goulb LM, Lee HM, Lehrer G, et al: Minocycline reduces gingival collagenolytic activity during diabetes. JPeridontRes 18:516-26, 1983.

- Goulb LM, et al: Tetracyclines imibit comective tissue breakdown: new therapeutic implications for an old family of drugs. Crit Rev Oral Med Pathol 2:297-322, 1991.

- Ingman T, Sorsa T, Suomalainen K, et al: Tetracycline inhibition and the cellular source of collagenase in gingival revicular fluid in different periodontal diseases. A review article. J Periodontol 64(2):82-8, 1993.

- Greenwald rheumatoid arthritis, Moak SA, et al: Tetracyclines suppress metalloproteinase activity in adjuvant arthritis and, in combination with flurbiprofen, ameliorate bone damage. J Rheumatol 19:927-38, 1992.

- Gomes BC, Golub LM, Ramammurthy NS: Tetracyclines inhibit parathyroid hormone induced bone resorption in organ culture. Experientia 40:1273-5, 1985.

- Yu LP Jr, SMith GN, Hasty KA, et al: Doxycycline inhibits Type XI collagenolytic activity of extracts from human osteoarthritic cartilage and of gelantinase. JRheumatol 18:1450-2, 1991.

- Thong YH, Ferrante A: Effect of tetracycline treatment of immunological responses in mice. Clin Exp Immunol 39:728-32, 1980.

- Pruzanski W, Vadas P: Should tetracyclines be used in arthritis? J Rheumatol 19: 1495-6, 1992.

- Editorial: Antibiotics as biological response modifiers. Lancet 337:400-1, 1991.

- Van Barr HMJ, et al: Tetracyclines are potent scavengers of the superoxide radical. Br J Dermatol 117:131-4, 1987.

- Wasil M, Halliwell B, Moorhouse CP: Scavenging of hypochlorous acid by tetracycline, rifampicin and some other antibiotics: a possible antioxidant action of rifampicin and tetracycline? Biochem Pharmacol 37:775-8, 1988.

- Breedveld FC, Trentham DE: Suppression of collagen and adjuvant arthritis by a tetracycline. Arthritis Rheum 31(1 Supplement)R3, 1988.

- Trentham, DE; Dynesium-Trentham rheumatoid arthritis: Antibiotic Therapy for Rheumatoid Arthritis: Scientific and Anecdotal Appraisals. Rheum Clin NA 21: 817-834, 1995.

- Panayi GS, et al: The importance of the T cell in initiating and maintaining the chronic synovitis of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 35:729-35, 1992.

- Sewell KL, Trentham DE: Pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 341 :283-86, 1993.

- Sewell KE, Furrie E, Trentham DE: The therapeutic effect of minocycline in experimental arthritis. Mechanism of action. JRheumatol 33(suppl):S106, 1991.

- Panayi GS, Clark B: Minocycline in the treatment of patients with Reiter's syndrome. Clin Erp Immunol 7: 100-1, 1989.

- Pott H-G, Wittenborg A, Junge-Hulsing G: Long-term antibiotic treatment in reactive arthritis. Lancet i:245-6, Jan 30, 1988.

- Skinner M, Cathcart ES, Mills JA, et al: Tetracycline in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism 14:727-732, 1971.

- Lauhio A, Leirisalo-Repo M, Lahdevirta J, et al: Double-blind placebo-controlled study of three-month treatment with Iymecycline in reactive arthritis, with special reference to Chlamydia arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatism 34:6-14, 1991.

- Lauhio A, Sorsa T, Lindy O, et al: The anticollagenolytic potential of Iymecycline in the long-term treatment of reactive arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatism 35: 195-198, 1992.

- Breedveld FC, Dijkmans BCA, Mattie H: Minocycline treatment for rheumatoid arthritis: an open dose finding study. JRheumatol 17:43-46, 1990.

- Kloppenburg M, Breedveld FC, Miltenburg AMM, et al: Antibiotics as disease modifiers in arthritis. Clin Exper Rheumatol l l(suppl 8):S113-S115, 1993.

- Langevitz P, et al: Treatment of resistant rheumatoid arthritis with minocycline: An open study. J Rheumatol 19: 1502-04, 1992.

- Tilley, B, et al: Minocycline in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A 48 week double-blind placebo controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 122:81, 1995.

- Mills, JA: Do Bacteria Cause Chronic Polyarthritis? N Enel J Med 320:245-246. January 26, 1989.

- Rothschild BM, et al: Symmetrical Erosive Peripheral Polyarthritis in the Late Archaic Period of Alabama. Science 241:1498-1502, Sept 16, 1988.

- Clark, HW, et al: Detection of Mycoplasma Antigens in Immune Complexes From Rheumatoid Arthritis Synovial Fluids. Ann Allergy 60:394-398, May 1988.

- Res PCM, et al: Synovial Fluid T Cell Reactivity Against 65kD Heat Shock Protein of Mycobacteria in Early Chronic Arthritis. Lancet ii:478-480, Aug 27, 1988.

- Cassell GH, et al: Mycoplasmas as Agents of Human Disease. N Engl J Med 304:80-89, Jan 8, 1981.

- Breedveld FC, et al: Minocycline Treatment for Rheumatoid Arthritis: An Open Dose Finding Study. J Rheumatol 17:43-46, January 1990.

- Phillips PE: Evidence implicating infectious agents in rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 6:87-94. 1988.

- Harris ED: Rheumatoid Arthritis, Pathophysiology and Implications for Therapy. N Engl J Med 322:1277-1289, May 3, 1990.

- Clark HW: The Potential Role of Mycoplasmas as Autoantigens and Immune Complexes in Chronic Vascular Pathogenesis. Am Jof Primatology 24:235-243. 1991.

- Silman AJ: Is Rheumatoid Arthritis an Infectious Disease? Br Med J 303:200 July 27, 1991.

- Clark HW: The Potential Role of Mycoplasmas as Autoantigens and Immune Complexes in Chronic Vascular Pathogenesis. Am J Primatol 24:235-243, 1991.

- Wheeler HB: Shattuck Lecture Healing and Heroism. NEngl JMed 322:1540-1548, May 24, 1990.

- Arnett FC: Revised Criteria for the Classification of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Bun Rheum Dis 38:1-6, 1989.

- Braanan W: Treatment of Chronic Prostatitis. Comparison of Minocycline and Doxycycline. Urology 5:631-636, 1975.

- Becker FT: Treatment of Tetracycline-Resistant Acne Vulgaris. Cutis 14:610-613. 1974.

- Cullen, SI: Low-Dose Minocycline Therapy in Tetracycline-Recalcitrant Acne Vulgaris. Cutis 21:101-105, 1978.

- Mattuccik, et al: Acute Bacterial Sinusitis. Minocycline vs.Amoxicillin. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surgery 112:73-76, 1986.

- Guillon JM, et al: Minocylcine-induced Cell-mediated Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis. Ann Intern Med 117:476-481, 1992.

- Gabriel SE, et al: Rifampin therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 17: 163-6, 1990.

- Caperton EM, et al: Cefiriaxone therapy of chronic inflammatory arthritis. Arch Intern Med 150:1677-1682, 1990.

- Ann Intern Med 117:273-280, 1992.

- Clive DM, et al: Renal Syndromes Associated with Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory drugs. NEngl JMed 310:563-572. March 1 l994.

- Piper, et al: Corticosteroid Use and Peptic Ulcer Disease: Role of Non-Steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs. Ann Intern Med 114:735-740, May 1, 1991.

- Allison MC, et al: Gastrointestinal Damage Associated with the Use of Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs. N Engl J Med 327:749-54, 1992.

- Fries JF:Postmarketing Drug Surveillance: Are Our Priorities Right? JRheumatol 15:389-390, 1988.

- Brooks PM, et al: Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs Differences and Similarities. NEngl JMed 324:1716-1724, June 13, 1991.

- Agrawal N: Risk Factors for Gastrointestinal Ulcers Caused by Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs). J Fam Prac 32:619-624, June 1991.

- Silverstein, F: Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and Peptic Ulcer Disease. Postgrad Med 89:33-30, May 15, 1991.

- Gabriel SE, et al: Risk for Serious Gastrointestinal Complications Related to Use of NSAIDs. Ann Intern Med 115:787-796 1991.

- Fries JF, et al: Toward an Epidemiology of Gastropathy Associated With NSAID Use. Gastroent 96:647-55, 1989.

- Armstrong CP, et al: NSAIDs and Life Threatening Complications of Peptic Ulceration. Gut 28:527-32, 1987.

- Murray MD, et al: Adverse Effects of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs on Renal Function. AnnInternMed 112:559, April 15, 1990.

- Cook DM: Safe Use of Glucocorticoids: How to Monitor Patients Taking These Potent Agents. Postgrad Med 91:145-154, Feb. 1992.

- Piper JM, et al: Corticosteroid Use and Peptic Ulcer Disease: Role of Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs. Ann Intern Med 114:735-740, May 1, 1991.

- Thompson JM: Tension Myalgia as a Diagnosis at the Mayo Clinic and Its Relationship to Fibrositis, Fibromyalgia, and Myofascial Pain Syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc 65:1237-1248, September 1990.

- Semble EL, et al: Therapeutic Exercise for Rheumatoid Arthritis and Osteoarthritis. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism 20:32-40, August 1990.

- O'Dell, J, Haire, C, Palmer, W, Drymalski, W, Wees, S, Blakely, K, Churchill, M, Eckhoff, J, Weaver, A, Doud, D, Erickson, N, Dietz, F, Olson, R, Maloney, P, Klassen, L, Moore, G, Treatment of Early Rheumatoid Arthritis with Minocycline or Placebo: Results of a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial, Arthritis & Rheumatism, 1997, 40:5, 842-848.

- Tilley, BC, Alarcón, GS, Heyse, SP, Trentham, DE, Neuner, R, Kaplan, DA, Clegg, DO, Leisen, JCC, Buckley, L, Cooper, SM, Duncan, H, Pillemer, SR, Tuttleman, M, Fowler, SE, Minocycline in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A 48-Week, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial, Annals of Internal Medicine, 1995, 122:2, 81-89.

- Bluhm, GB, Sharp, JT, Tilley, BC, Alarcon, GS, Cooper, SM, Pillemer, SR, Clegg, DO, Heyse, SP, Trentham, DE, Neuner, R, Kaplan, DA, Leisen, JC, Buckley, L, Duncan, H, Tuttleman, M, Shuhui, L, Fowler, SE, Radiographic Results from the Minocycline in Rheumatoid Arthritis (MIRA) Trial, Journal of Rheumatology, 1997, 24:7, 1295-1302.

- Breedveld, FC, Editorial: Minocycline in Rheumatoid Arthritis, Arthritis & Rheumatism, 1997, 40:5, 794-796.

- Breedveld, FC, Letters: Reply to Minocycline-Induced Autoimmune Disease, Arthritis & Rheumatism, 1998, 41:3, 563-564.

- Fox, R, Sharp, D, Editorial: Antibiotics as Biological Response Modifiers, The Lancet, 1991, 337:8738, 400-401.

- Greenwald, rheumatoid arthritis, Golub, LM, Lavietes, B, Ramamurthy, NS, Gruber, B, Laskin, RS, McNamara, TF, Tetracyclines Inhibit Human Synovial Collagenase In Vivo and In Vitro, Journal of Rheumatology, 1987, 14:1, 28-32.

- Griffiths, B, Gough, A, Emery, P, Letters: Minocycline-Induced Autoimmune Disease: Comment on the Editorial by Breedveld, Arthritis & Rheumatism, 1998, 41:3, 563.

- Kloppenburg, M, Breedveld, FC, Miltenburg, AMM, Dijkmans, BAC, Antibiotics as Disease Modifiers in Arthritis, Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology, 1993, 11: Suppl. 8, S113-S115.

- Kloppenburg, M, Breedveld, FC, Terwiel, JPh, Mallee, C, Dijkmans, BAC, Minocycline in Active Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial, Arthritis & Rheumatism, 1994, 37:5, 629-636.

- Kloppenburg, M, Mattie, H, Douwes, N, Dijkmans, BAC, Breedveld, FC, Minocycline in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis: Relationship of Serum Concentrations to Efficacy, Journal of Rheumatology, 1995, 22:4, 611-616.

- Lauhio, A, Leirisalo-Repo, M, Lähdevirta, J, Saikku, P, Repo, H, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Three-Month Treatment with Lymecycline in Reactive Arthritis, with Special Reference to Chlamydia Arthritis, Arthritis & Rheumatism, 1991, 34:1, 6-14.

- Lauhio, A, Sorsa, T, Lindy, O, Suomalainen, K, Saari, H, Golub, LM, Konttinen, YT, The Anticollagenolytic Potential of Lymecycline in the Long-Term Treatment of Reactive Arthritis, Arthritis & Rheumatism, 1992, 35:2, 195-198.

- Paulus, HE, Editorial: Minocycline Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis, Annals of Internal Medicine, 1995, 122:2, 147-148.

- Pruzanski, W, Vadas, P, Editorial: Should Tetracyclines be Used in Arthritis?, Journal of Rheumatology, 1992, 19:10, 1495-1497.

- Sieper, J, Braun, J, Editorial: Treatment of Reactive Arthritis with Antibiotics, British Journal of Rheumatology, July 1998.

- Baseman, JB, Tully, JG, Mycoplasmas: Sophisticated, Reemerging, and Burdened by Their Notoriety, CDC's Emerging Infectious Diseases, 1997, 3:1, 21-32.

- Franz, A, Webster, ADB, Furr, PM, Taylor-Robinson, D, Mycoplasmal Arthritis in Patients with Primary Immunoglobulin Deficiency: Clinical Features and Outcome in 18 Patients, British Journal of Rheumatology, 1997, 36:6, 661-668.

- Hakkarainen K, Turunen, H, Miettinen, A, Karppelin, M, Kaitila, K, Jansson, E, Mycoplasmas and Arthritis, Annals of Rheumatic Diseases, 1992, 51, 1170-1172.

- Hoffman, RH, Wise, KS, Letters: Reply to Mycoplasmas in the Joints of Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis and Other Inflammatory Rheumatic Disorders, Arthritis & Rheumatism, 1998, 41:4, 756-757.

- Schaeverbeke, T, Bébéar, C, Lequen, L, Dehais, J, Bébéar, C, Letters: Mycoplasmas in the Joints of Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis and Other Inflammatory Rheumatic Disorders: Comment on the Article by Hoffman et al., Arthritis & Rheumatism, 1998, 41:4, 754-756.

- Schaeverbeke, T, Gilroy, CB, Bébéar, C, Dehais, J, Taylor-Robinson, D, Mycoplasma fermentans, But Not M penetrans, Detected by PCR Assays in Synovium from Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis and Other Rheumatic Disorders, Journal of Clinical Pathology, 1996, 49, 824-828.

- Aoki, S, Yoshikawa, K, Yokoyama, T, Nonogaki, T, Iwasaki, S, Mitsui, T, Niwa, S, Role of Enteric Bacteria in the Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis: Evidence for Antibodies to Enterobacterial Common Antigens in Rheumatoid Sera and Synovial Fluids, Annals of Rheumatic Diseases, 1996, 55:6, 363-369.

- Blankenberg-Sprenkels, SHD, Fielder, M, Feltkamp, TEW, Tiwana, H, Wilson, C, Ebringer, A, Antibodies to Klebsiella pneumoniae in Dutch Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis and Acute Anterior Uveitis and to Proteus mirabilis in Rheumatoid Arthritis, Journal of Rheumatology, 1998, 25:4, 743-747.

- Ebringer, A, Ankylosing Spondylitis is Caused by Klebsiella: Evidence from Immunogenetic, Microbiologic, and Serologic Studies, Rheumatic Disease Clinics of North America, 1992, 18:1, 105-121.

- Erlacher, L, Wintersberger, W, Menschik, M, Benke-Studnicka, A, Machold, K, Stanek, G, Söltz-Szöts, J, Smolen, J, Graninger, W, Reactive Arthritis: Urogenital Swab Culture is the Only Useful Diagnostic Method for the Detection of the Arthritogenic Infection in Extra-Articularly Asymptomatic Patients with Undifferentiated Oligoarthritis, British Journal of Rheumatology, 1995, 34:9, 838-842.

- Gaston, JSH, Deane, KHO, Jecock, RM, Pearce, JH, Identification of 2 Chlamydia trachomatis Antigens Recognized by Synovial Fluid T Cells from Patients with Chlamydia Induced Reactive Arthritis, Journal of Rheumatology, 1996, 23:1, 130-136.

- Gerard, HC, Branigan, PJ, Schumacher Jr, HR, Hudson, AP, Synovial Chlamydia trachomatis in Patients with Reactive Arthritis/ Reiter's Syndrome Are Viable But Show Aberrant Gene Expression, Journal of Rheumatology, 1998, 25:4, 734-742.

- Granfors, K, Do Bacterial Antigens Cause Reactive Arthritis?, Rheumatic Disease Clinics of North America, 1992, 18:1, 37-48.

- Granfors, K, Merilahti-Palo, R, Luukkainen, R, Möttönen, T, Lahesmaa, R, Probst, P, Märker-Hermann, E, Toivanen, P, Persistence of Yersinia Antigens in Peripheral Blood Cells from Patients with Yersinia Enterocolitica 0:3 Infection with or without Reactive Arthritis, Arthritis & Rheumatism, 1998, 41:5, 855-862.

- Inman, RD, The Role of Infection in Chronic Arthritis, Journal of Rheumatology, 1992, 19, Supplement 33, 98-104.

- Layton, MA, Dziedzic, K, Dawes, PT, Letters to the Editor: Sacroiliitis in an HLA B27-negative Patient Following Giardiasis, British Journal of Rheumatology, 1998, 37:5, 581-583.

- Mäki-Ikola, O, Lehtinen, K, Granfors, K, Similarly Increased Serum IgA1 and IgA2 Subclass Antibody Levels against Klebsiella pneumoniæ Bacteria in Ankylosing Spondylitis Patients With/Without Extra-Articular Features, British Journal of Rheumatology, 1996, 35:2, 125-128.

- Morrison, RP, Editorial: Persistent Chlamydia trachomatis Infection: In Vitro Phenomenon or in Vivo Trigger of Reactive Arthritis?, Journal of Rheumatology, 1998, 25:4, 610-612.

- Mousavi-Jazi, M, Boström, L, Lövmark, C, Linde, A, Brytting, M, Sundqvist, V-A, Infrequent Detection of Cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr Virus DNA in Synovial Membrane of Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis, Journal of Rheumatology, 1998, 25:4, 623-628.

- Nissilä, M, Lahesmaa, R, Leirisalo-Repo, M, Lehtinen, K, Toivanen, P, Granfors, K, Antibodies to Klebsiella pneumoniæ, Escherichia coli, and Proteus mirabilis in Ankylosing Spondylitis: Effect of Sulfasalazine Treatment, Journal of Rheumatology, 1994, 21:11, 2082-2087.

- Svenungsson, B, Editorial Review: Reactive Arthritis, International Journal of STD & AIDS, 1995, 6:3, 156-160.

- Tani, Y, Tiwana, H, Hukuda, S, Nishioka, J, Fielder, M, Wilson, C, Bansal, S, Ebringer, A, Antibodies to Klebsiella, Proteus, and HLA-B27 Peptides in Japanese Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis and Rheumatoid Arthritis, Journal of Rheumatology, 1997, 24:1, 109-114.

- Tiwana, H, Walmsley, RS, Wilson, C, Yiannakou, JY, Ciclitira, PJ, Wakefield, AJ, Ebringer, A, Characterization of the Humoral Immune Response to Klebsiella Species in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Ankylosing Spondylitis, British Journal of Rheumatology, 1998, 37:5, 525-531.