Muhammad Ali, boxing icon and global goodwill ambassador, dies at 74

Matt Schudel and Bart Barnes

Muhammad Ali, the charismatic three-time heavyweight boxing champion of the world, who declared himself “the greatest” and proved it with his fists, the force of his personality and his magnetic charisma, and who transcended the world of sports to become a symbol of the antiwar movement of the 1960s and a global ambassador for cross-cultural understanding, died June 3 at a hospital in Scottsdale, Ariz., where he was living. He was 74.

His family released a statement confirming his death. The boxer had been hospitalized with respiratory problems related to Parkinson’s disease, which had been diagnosed in the 1980s.

Mr. Ali dominated boxing in the 1960s and 1970s and held the heavyweight title three times. His fights were among the most memorable and spectacular in history, but he quickly became at least as well known for his colorful personality, his showy antics in the ring and his standing as the country’s most visible member of the Nation of Islam.

[Brewer: Ali did more than talk about greatness — he embodied it]

When he claimed the heavyweight championship in 1964, with a surprising upset of the formidable Sonny Liston, Mr. Ali was known by his name at birth, Cassius Clay. The next day, he announced that he was a member of the Nation of Islam, a move considered shocking at the time, especially for an athlete. He soon changed his name to Muhammad Ali.

“I know where I’m going and I know the truth, and I don’t have to be what you want me to be,” he said at the time, signaling his intent to define his career on his own terms. “I’m free to be what I want.”

Mr. Ali came to represent a new kind of athlete, someone who created his own style in defiance of the traditions of the past. Glib, handsome and unpredictable, he was perfectly suited to television, and he became a fixture on talk shows as well as sports programs.

He often spoke in rhyme, using it to belittle his opponents and embellish his own abilities. “This is the legend of Cassius Clay, the most beautiful fighter in the world today,” he said before his 1964 title bout. “The brash young boxer is something to see, and the heavyweight championship is his destiny.”

One of his assistants, Drew “Bundini” Brown, captured his lithe, graceful presence in the ring, saying Mr. Ali would “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.” The description entered the vernacular.

A funeral for Mr. Ali will be held in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky, according to The Associated Press. City officials scheduled a memorial service Saturday.

Mr. Ali appealed to people of every race, religion and background, but during the turbulent, divisive 1960s, he was particularly seen as a champion of African Americans and young people. Malcolm X, who recruited Mr. Ali to the Nation of Islam, once anointed him “the black man’s hero.”

[George Foreman on Ali’s death: ‘Part of me just passed with him’]

In 1967, after Mr. Ali had been heavyweight champion for three years, he refused to be inducted into the military during the Vietnam War. Despite the seeming contradiction of a boxer advocating nonviolence, he gave up his title in deference to the religious principle of pacifism.

“Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam,” Mr. Ali said in 1967, “while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights?”

He was supported by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who supported his decision to become a conscientious objector as “a very great act of courage.”

Mr. Ali’s heavyweight title was immediately removed, and he was banned from boxing for more than three years. He was sentenced to five years in prison, but a prolonged appeals process kept him from serving time.

Mr. Ali’s decision outraged the old guard, including many sportswriters and middle Americans, who considered the boxer arrogant and unpatriotic. But as the cultures of youth and black America were surging to the fore in the late 1960s, Mr. Ali was gradually transformed, through his sheer magnetism and sense of moral purpose, into one of the most revered figures of his time.

A casual statement he made in 1966 — “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong” — distilled the antiwar views of a generation.

“Ali, along with Robert Kennedy and the Beatles in the persona of John Lennon, captured the ’60s to perfection,” writer Jack Newfield told Thomas Hauser, the author of a 1991 oral biography, “Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times.”

“In a rapidly changing world,” Newfield added, “he underwent profound personal change and influenced rather than simply reflected his times.”

Later, as Mr. Ali’s boxing career receded into the past, and as neurological infirmities left him increasingly slowed and silenced, he became a symbol of unity and brotherhood, someone whose very presence and image acquired an aura of the spiritual. He was greeted by thousands whenever he toured the world.

[The best knockouts of Ali’s career]

He “evolved from a feared warrior,” Hauser wrote, “to a benevolent monarch and ultimately to a benign venerated figure.”

In 1996, Mr. Ali stood at the top of a podium during the opening ceremonies of the Summer Games in Atlanta in what became one of the most indelible moments in Olympic history. Shakily holding the torch as an estimated 3 billion people watched on television, Mr. Ali lit the Olympic flame, marking the official beginning of the Games. He stood alone before the world, a fragile, yet still indomitable demigod.

Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. was born Jan. 17, 1942, in Louisville. His father was a sign-painter, and his mother was a domestic houseworker.

Mr. Ali played few sports as a child, but he began boxing at age 12 to exact revenge on a thief who had stolen his bicycle. He quickly became enamored of the sport, and he won several national amateur boxing championships before he graduated from high school in 1960.

That year, he went to the Summer Olympics in Rome and came back with the gold medal in the light-heavyweight division, defeating a three-time European champion from Poland. He was only 18.

Mr. Ali then became a professional fighter, signing a contract with 12 wealthy supporters who called themselves the Louisville sponsoring group, or syndicate. After working briefly with light-heavyweight champion Archie Moore, Mr. Ali joined forces with trainer Angelo Dundee, whom he had met several years earlier. Dundee took Mr. Ali to Miami Beach, Fla., to train at the fabled Fifth Street Gym on a then-run-down street corner.

At the time, greater Miami was as segregated as any city in the South, and Mr. Ali could not try on clothes at white-owned department stores. The police sometimes stopped to question him when he was doing his road work, running several miles over a causeway from Miami to Miami Beach while wearing high-topped boots.

In the ring, Mr. Ali had an unconventional, almost casual style, lightly bouncing on his feet while keeping his hands low at his sides. Some sportswriters considered it an almost suicidal approach, but Dundee trusted in Mr. Ali’s foot speed and quick reflexes, which enabled him to evade punches.

Because of his unusual stance and constant movement, Mr. Ali’s punches arrived from unexpected angles, carrying devastating power. As other fighters hunkered in the center of the ring, with their fists doubled in front of their faces, Mr. Ali danced around them, seemingly at play.

Still known by his original name of Cassius Clay, he began to develop a mass following soon after his first professional fight in 1960. He vanquished one opponent after another, often predicting the round in which he would claim victory. He wore flashy white boxing boots and attracted attention with his comical verse.

From the beginning, Mr. Ali had a flair for showmanship. At 19, he was the subject of a multi-page spread of photographs in Life magazine after he convinced the photographer, Flip Schulke, that he had long trained underwater to improve his endurance and strength. In fact, Mr. Ali had never been in a swimming pool before he posed for the eye-catching pictures.

As the Feb. 25, 1964, title bout with Liston approached, Mr. Ali was a 7-to-1 underdog, and few gave him a chance against the champion, a menacing ex-convict with devastating power. But Mr. Ali, then 22, had filled out to a well-proportioned 6-foot-3 and 210 pounds. He was proudly aware of his physical beauty, especially in contrast to the glowering, silent Liston, whom he taunted as “a big, ugly bear.”

Engaging in a campaign of psychological warfare, Mr. Ali drove to Liston’s training camp at the wheel of a bus, with the slogan “World’s Most Colorful Fighter” painted on the side, challenging the champion to come out and fight him in the street.

“He’s too ugly to be the world champ,” Mr. Ali said. “The world champ should be pretty like me.”

He recited rhymes that reduced Liston to a comic punch line:

Who would have thought when they came to the fight

That they’d witness the launching of a human satellite?

Yes, the crowd did not dream, when they put up their money,

That they would see a total eclipse of the Sonny.

At the weigh-in the day of the fight, Mr. Ali appeared to lose control, shouting at Liston and staging an out-of-control performance unlike anything seen in boxing before. He was fined $2,500 on the spot.

A doctor measured his heart rate at 120 beats per minute and said if Mr. Ali’s elevated blood pressure didn’t return to normal, the fight would be called off. The boxing commission’s physician offered this summary of Mr. Ali’s condition: “emotionally unbalanced, scared to death, and liable to crack up before he enters the ring.”

In fact, it was an elaborate ruse on the part of Mr. Ali and his camp, and within an hour his heart rate and blood pressure were back to normal. Mr. Ali said his plan was to appear deranged, to make Liston think that he was in the ring with an opponent who might actually be crazy.

During the fight itself, Mr. Ali controlled the pace until late in the fourth round, when a burning substance somehow got in his eyes. He could barely see and, after the round, pleaded with Dundee to stop the fight. To this day, no one is sure whether the caustic substance in his eyes was a liniment applied to Liston’s face to stanch bleeding from cuts or whether it was something more nefarious.

Dundee, calling on his years of experience, splashed water in Mr. Ali’s eyes with a sponge and pushed him back in the ring for the fifth round, telling him to keep moving to avoid Liston’s onslaught.

“You can’t quit now,” Dundee said. “This is the big one, Daddy! Run!”

Mr. Ali kept on the move, and his eyes gradually cleared by the end of the fifth round. He resumed his attack in the sixth, pummeling Liston and opening a deep cut under his left eye. As the bell rang to open the seventh round, the demoralized Liston sat on his stool, refusing to continue the fight.

When it was apparent that Mr. Ali was the new champion, he shouted to the sportswriters at ringside, “I am the greatest! I am the greatest! I shook up the world!”

After Mr. Ali’s public conversion to the Nation of Islam — often called the “Black Muslims” at the time — he was seen by many conventional sports fans as a sinister, somewhat alien figure. Seemingly overnight, he had gone from a bubbly, boyish champion with a gift of gab to a quasi-revolutionary.

“The first time I felt truly spiritual in my life was when I walked into the Muslim temple in Miami,” Mr. Ali told Hauser for his 1991 biography.

He abandoned what he called his “slave name” — the original Cassius Marcellus Clay was a white anti-slavery crusader in 19th-century Kentucky — and traveled to Africa, growing close to Malcolm X and other members of the Nation of Islam.

To many white people and Christians of the time, Mr. Ali seemed dangerous, and not just for his ability to throw a punch. Most media outlets continued to refer to him as “Clay,” even as he prepared for a second bout with Liston.

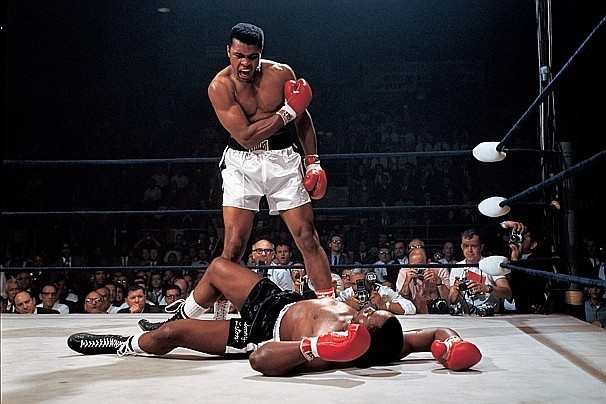

After several delays, the fight took place on May 25, 1965, in Lewiston, Maine. Liston was still favored, but in the opening round, he ended up on his back in the center of the ring as confusion reigned.

Mr. Ali stood over his fallen opponent, shouting and gesturing for him to stand up. But Liston stayed down, his eyes darting from one side to the other. He eventually rose to his feet, and the fight briefly resumed until the referee, former champion Jersey Joe Walcott, stepped between the combatants.

He ruled that Liston had been on the canvas for 10 seconds and that the fight was over: Mr. Ali had retained his title by knockout.

The unexpected finish stirred enormous controversy. Mr. Ali’s knockout blow was dubbed the “phantom punch” by skeptics, and others openly speculated that Liston had taken a “dive” in order to collect a payoff from gamblers. Slow-motion film appeared to show that Mr. Ali landed a short, powerful punch with his right hand on Liston’s jaw, but doubt about the result never completely went away.

After the second Liston match, Mr. Ali marched through a string of challengers, including ex-champ Floyd Patterson and Britons Henry Cooper and Brian London. On Feb. 6, 1967, he faced 6-foot-6-inch Ernie Terrell, who called Mr. Ali “Clay” in the weeks before the fight.

“I’m gonna give him a whupping and a spanking, and a humiliation,” an angry Mr. Ali said before the fight. “I’ll keep on hitting him, and I’ll keep talking. Here’s what I’ll say. ‘Don’t you fall, Ernie.’ Wham! ‘What’s my name?’ Wham! I’ll just keep doing that until he calls me Muhammad Ali. I want to torture him. A clean knockout is too good for him.”

True to his word, and showing a vindictive, even cruel streak, Mr. Ali punished Terrell throughout the bout. Instead of knocking him out, Mr. Ali battered the challenger with a barrage of punches to the eyes as he shouted, “What’s my name?”

“It was a side of him so out of character that to this day I find it hard to believe it was him,” sportswriter Jerry Izenberg told Hauser for “Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times.”

“I saw it. I was there, and it was evil. He was trying to hurt Terrell. Ali went out there to make it painful and embarrassing and humiliating for Ernie Terrell. It was a vicious ugly horrible fight.”

It took months for Terrell’s vision to return to normal.

In March 1967, Mr. Ali won a seventh-round knockout over Zora Folley to run his record to a perfect 28-0. He was 25 and just entering his athletic prime when the legal problems surrounding his refusal to enter the military forced a premature end to his career.

He was condemned as a draft-dodger and denounced in Congress, but he maintained that his Muslim beliefs forbade him to go to war. For three years, Mr. Ali spoke on college campuses and on television shows, including a series of sometimes contentious interviews with sportscaster Howard Cosell.

Mr. Ali’s boxing license was finally restored in 1970, and a year later the U.S. Supreme Court vacated his conviction for draft evasion. After two tuneup fights, the 29-year-old boxer sought to regain his heavyweight title from the new champion, Joe Frazier, in a highly touted fight at New York’s Madison Square Garden on March 8, 1971.

Each boxer was guaranteed at least $2.5 million, the highest payday for any athlete up to that time. Frazier knocked Ali down in the 15th and final round and won the fight by unanimous decision. Afterward, both fighters were treated at hospitals.

Mr. Ali defeated Frazier in a rematch in January 1974, but by then the heavyweight title was in the hands of George Foreman. Mr. Ali sought to recapture his crown by facing Foreman in an international spectacle in Kinshasa, Zaire (now Congo), dubbed the “Rumble in the Jungle.”

Foreman, seven years younger than the 32-year-old Mr. Ali, had won 40 consecutive fights without a loss. None of his previous eight fights had lasted longer than two rounds, including an impressive performance in which he knocked Frazier to the canvas six times.

Before the fight, which took place on Oct. 30, 1974, Mr. Ali used the same kind of verbal attack on Foreman that he had unleashed on Liston a decade earlier. He belittled the hulking champion — then considered surly and unlikable, long before his second act as the affable pitchman of electronic grilling devices — as “the Mummy.”

During the fight, Mr. Ali tried a new and dangerous tactic, which he dubbed “rope-a-dope.” He often backed into the ropes, protecting his face with his hands as he allowed Foreman to slug him with one punch after another.

Somehow, Mr. Ali remained standing as he absorbed the barrage, and the ploy depleted Foreman’s strength and confidence.

“I went out and hit Muhammad with the hardest shot to the body I ever delivered to any opponent,” Foreman told Hauser. “Anybody else in the world would have crumbled.”

Mr. Ali began to goad Foreman in the ring, saying, “Show me something, George. That don’t hurt.” As the bell rang for the eighth round, he told Foreman, “Now it’s my turn.”

He stayed on the ropes for most of the round, parrying Foreman’s blows and fighting back with counterpunches. He landed a solid right hand on Foreman’s chin, driving the champion to the canvas. Mr. Ali’s knockout victory was considered almost miraculous and took on symbolic importance because it took place on African soil.

It had been more than 10 years since Mr. Ali first won the title, and seven years since he relinquished it. When he reclaimed the heavyweight championship in such dramatic fashion, many observers considered it one of the most remarkable displays of endurance and boxing skill in history.

“I fought that fight over in my head a thousand times,” Foreman told Hauser for his biography of Mr. Ali. “And then, finally, I realized I’d lost to a great champion; probably the greatest of all time.”

Weeks after Mr. Ali regained his crown, his restoration was made complete when he was invited to the White House by President Gerald R. Ford. Once a maligned outcast, Mr. Ali was now an esteemed figure of international renown.

After three title defenses, Mr. Ali agreed to face Frazier for a third time in the Philippines, in what became known as the “Thrilla in Manila.” In the weeks before the bout, Mr. Ali’s gamesmanship took on a personal, racially tinged tone as he insulted Frazier as a “gorilla” and relentlessly mocked him as ignorant and ugly. He pulled out a toy gorilla at a press conference as a gesture of contempt.

The fight took place on Oct. 1, 1975, in brutally hot conditions. The fighters battled on against pain and fatigue, both refusing to yield.

“I hit him with punches that bring down the walls of a city,” Frazier later said. “What held him up?”

After the 14th round, both of Frazier’s eyes were swollen shut, and the referee had to lead him back to his corner. Frazier’s trainer tossed a towel into the ring, signaling the end of the fight.

Mr. Ali was so exhausted, he could barely move to acknowledge victory.

“It’s the closest I’ve come to death,” he said.

The two fighters were linked in history, but the animosity built up before the fight would fester for years until Mr. Ali formally apologized in 2001.

In 1978, an aging and poorly prepared Mr. Ali lost his championship to Leon Spinks. He defeated Spinks in a rematch later that year to become the first heavyweight to win the title three times, then he announced his retirement.

But he returned to the ring for two ill-advised matches in the early 1980s, both of which he lost, before retiring in 1981 with a record of 56-5. He was already showing signs of slurred speech and general sluggishness, which only grew worse with time.

His condition was initially called Parkinson’s syndrome, which many thought — correctly or not — was caused or exacerbated by the thousands of punches he absorbed throughout his career. Some doctors and supporters insisted that Mr. Ali was mentally alert, but by the time the boxer was in his 50s, he had noticeable tremors in his limbs and spoke in a halting whisper, if at all.

Judged purely for his boxing skills, Mr. Ali ranks among the greatest heavyweights ever, alongside Joe Louis, Jack Johnson, Jack Dempsey and Rocky Marciano. But he possessed a quality that reached beyond his accomplishments in the ring to make him recognized by millions the world over.

Even in his diminished physical state, Mr. Ali was admired not just as a supreme athlete but as a hero, as a symbol of understanding and hope. Presidents sometimes called on him to make diplomatic visits abroad, and in 1990 he helped return several U.S. hostages held in Iraq. President Obama said in a statement that he keeps a photograph of Mr. Ali and a pair of his boxing gloves in his private study at the White House.

A 1996 documentary about Mr. Ali’s 1974 battle with Foreman, “When We Were Kings,” won an Academy Award for best documentary. A Hollywood feature film about his life, starring Will Smith, was released in 2001. He was named to the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990.

As perhaps the best-known Muslim in the United States, he issued a plea for peace after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. He continued to travel and make public appearances, often for charity, until shortly before his death. Even in the presence of presidents, popes and other world leaders, Mr. Ali was always the most famous person in the room. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, by President George W. Bush in 2005.

Mr. Ali’s first three marriages, to Sonji Roi, Belinda Boyd and Veronica Porsche, ended in divorce.

Survivors include his fourth wife, Yolanda “Lonnie” Williams, whom he married in November 1986; seven children from his marriages; two other children he acknowledged as his own; a brother; and numerous grandchildren.

Over time, Mr. Ali’s ties with the Nation of Islam loosened, but they were never completely severed. He lived for many years on a rural estate in Berrien Springs, Mich., and later had homes outside Louisville and near Scottsdale, Ariz.

Mr. Ali often visited prisons and hospitals and, throughout his life, used simple sleight-of-hand tricks to connect with children and adults all over the globe, until his deteriorating physical condition led him to curtail his public appearances.

From a boxing ring in Manila to villages in Zaire to the Olympic Games in Atlanta, he had a radiant presence that seemed more in keeping with that of an international religious leader than a retired athlete. More than almost any other figure of his age, Mr. Ali was recognized and honored as a citizen of the world.

“Look at all those lights on all those houses,” Mr. Ali told Esquire magazine writer Bob Greene in 1983, while flying into Washington’s National Airport. “Do you know I could walk up to any one of these houses, and knock on the door, and they would know me?

“It’s a funny feeling to look down on the world and know that every person knows me.”

Read more Washington Post obituaries

Joe Frazier, boxing champion who battled Ali, dies at 67

Angelo Dundee, trainer of Ali and other boxing champions, dies at 90

Ernie Terrell, boxer who lost to a taunting Muhammad Ali in 1967, dies at 75

SEE PHOTO GALLERY