Baku: City that Oil Built

Farid Alakbarov

![]()

Azerbaijan has long been known for its rich oil resources. The earliest exploration of onshore oil fields goes back at least to the 7th century BC, during the age of the Median kingdom in what is now Southern Azerbaijan [Iran]. The Median province that bordered Assyria became the first place in the world to extract oil from wells. Beginning in the 5th century BC, oil was lifted from wells in leather buckets.

Oil played an important role in the everyday lives of the Medians, Caspians and other ancient tribes of Azerbaijan. As fuel, it was used to fill their lamps of clay and metal. Oil also made an effective weapon; Median warriors would apply oil to the tips of their arrows, javelins and projectiles. Once lit, these objects were hurled or catapulted into enemy camps and ships. Ancient Greeks referred to this ancient weapon flame-thrower as "Median oil".

During the Middle Ages, oil was extracted in Azerbaijan on a larger scale - especially from the Absheron peninsula. In the 10th to 13th centuries, "light oil" was extracted from the Balakhani village and "heavy oil" was extracted from Surakhani.

Above: Fireworshippers' Temple at Atashgah, not far from Baku's International Airport, was built by Zoroastrians (Parsees from India). Today a fire fed by gas into the center of the cupola burns constantly.

Azerbaijanis have known how to distill oil since the early centuries AD. Thirteenth - century geographer Ibn Bekran writes that oil was distilled in Baku in order to minimize its bad smell and make it more appropriate for medicinal applications.

Marco Polo wrote in the 13th century that the excellent Baku oil was used for illuminating houses and treating skin diseases. Azerbaijani geographer Abd ar-Rashid Bakuvi (14th-15th centuries) noted that up to 200 camel bales of oil were exported from Baku every day. Since a single "camel bale" is the equivalent of approximately 300 kg of oil, this would have meant a regular supply of 60,000 kg of oil per day.

![]() According to Hamdullah Gazvini (14th century), workers used to fill the oil wells with water so that the oil would rise to the surface. Then the oil was collected in leather bags made from the skins of Caspian seals. In 1669, medieval scholar Muhammad Mu'min likewise noted that these types of leather bags were being used for the storage and transportation of oil.

According to Hamdullah Gazvini (14th century), workers used to fill the oil wells with water so that the oil would rise to the surface. Then the oil was collected in leather bags made from the skins of Caspian seals. In 1669, medieval scholar Muhammad Mu'min likewise noted that these types of leather bags were being used for the storage and transportation of oil.

Right: Political cartoon on the front cover of Molla Nasraddin publication, showing how Azerbaijan (depicted as the beautiful lady) was being both courted and threatened by foreign lands because of oil resources. 1922

In 1572, British businessman Jeffrey Decket visited Baku and recorded his observations about the city. According to him, a large amount of oil had seeped to the surface of the earth in the vicinity of Baku. Many people traveled there to obtain this oil - even from considerable distances.

Decket wrote that a type of black oil, called "naft", was used throughout the country to illuminate homes. This oil was also transported to other countries on the backs of mules and donkeys, in caravans of 400 to 500 animals. In the vicinity of Baku, he noted a white and very valuable kind of oil. He supposed that "it was similar to our petroleum (the mountainous oil)."

In 1601 the Iranian historian Amin Ahmad ar-Razi mentions that there were 500 oil wells in the vicinity of Baku from which oil was extracted on a daily basis. Katib Chelebi, the Turkish historian of the 17th century AD, quotes these same figures.

Lerch, the 17th-century German traveler, writes that there were 350-400 oil wells in the Absheron peninsula and that there was a single well in Balakhani village where approximately 3,000 kg of oil was extracted on a daily basis.

![]() Left: Haji Zeynalabdin's home in the Inner City with the cannon set up in front of it. This Baroque mansion was demolished in the 1970s and its place, a Soviet style building, known as the Encyclopedia Building took its place.

Left: Haji Zeynalabdin's home in the Inner City with the cannon set up in front of it. This Baroque mansion was demolished in the 1970s and its place, a Soviet style building, known as the Encyclopedia Building took its place.

German scholar and secretary of the Swedish Embassy, Engelbert Kaempfer (1651-1716), who visited Baku in 1683, wrote in his diary that the oil wells there were up to 27 meters deep, with walls covered in limestone or wood. During this period, Baku oil was already being exported to Russia and other countries in Eastern Europe.

He writes that in Surakhani, a village alone not far from Baku, between 2,700 kg to 3,000 kg of oil were extracted daily for export. This quantity filled 80 carriages carrying 8 oil bags each.

As far back as the Middle Ages, oil extraction led to the pollution of the environment, though, obviously, this was not a primary concern at the time. Azerbaijani author Muhammad Yusif Shirvani wrote in his "Tibbname" (Book of Medicine, 1712) that as a result of oil and sulfur extraction, both the soil and water of the area had become contaminated.

According to British missionary Father Willot, who visited Azerbaijan in 1689, the annual income that the Safavi shahs derived from Baku oil was 7,000 tumans, or 420,000 French livres (the French currency that was used before the franc was introduced in 1799).

Source of Sacred Fire

Before the introduction of Islam in the region at the end of the 7th century AD, the people who lived in what is now known as Azerbaijan were Zoroastrians who worshipped fire. The area around Baku became a spiritual hub for Zoroastrianism because of a curious natural phenomenon: so much oil is buried deep inside the ground that the gas seeps through fissures in the surface and catches on fire. It was at these sites, which were considered sacred, that fire-worshipping temples were built in Surakhani and other districts near Baku on the Absheron peninsula.

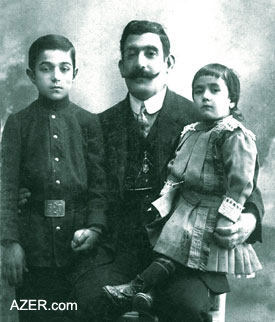

![]() Right: Gochu Mammad Hanifa with his children, Abbas and Ana Khanim. 1911. Mammad Hanifa succeeded in preventing the Bolsheviks and Armenians from entering Baku's Inner City during the massacre that swept the city in March 1918. In 1920 when the Bolsheviks took power, Hanifa was arrested and assassinated as an "Enemy of the People".

Right: Gochu Mammad Hanifa with his children, Abbas and Ana Khanim. 1911. Mammad Hanifa succeeded in preventing the Bolsheviks and Armenians from entering Baku's Inner City during the massacre that swept the city in March 1918. In 1920 when the Bolsheviks took power, Hanifa was arrested and assassinated as an "Enemy of the People".

Even today, a gas torch burns from atop Baku's famous Maiden's Tower. Some scholars believe that the Maiden's Tower was used for defense purposes. Others suggest that it was used as a Zoroastrian temple as far back as 2,500 years ago. Archeological excavations have revealed that there was an altar located near the Maiden's Tower. The altar's stone basin contains traces of oil and fire, leading researchers to interpret that this holy basin was kept filled with oil in order to keep an eternal flame burning. Professor Davud Akhundov also believes that there was a "Temple of Fire in the Water" located on the seacoast in front of the Maiden's Tower in the Caspian during the 1st millennium BC.

Oil and gas continued to be used as a source for Holy Fire, even during the Middle Ages, after most Azerbaijanis had converted to Islam. In the 18th century, the burning oil of the Absheron peninsula attracted fire worshippers from India who built a Temple of Fire (Atashgah) in the Surakhani village near Baku. These Zoroastrians worshipped the eternal, sacred fire that was being nourished from the gas and oil burning inside the temple.

In the 19th century, French novelist Alexander Dumas visited Atashgah and wrote: "With the exception of Frenchmen who rarely travel, the whole world is aware of the Atashgah in Baku.My compatriots who want to see the fire-worshippers must be quick because already there are so few left in the temple, just one old man and two younger ones about 30-35 years old."

Dumas described the temple as follows: "We went inside the temple through the gates, which were entirely enveloped in flames. The prayer room with the cupola is erected in the middle of a large quadrangular court; the eternal fire is ablaze right in the middle of the prayer room."

Oil and oil-based products were widely used for medicinal purposes during the Middle Ages, according to manuscripts on medical and pharmaceutical practices that are currently held at Baku's Institute of Manuscripts. Mineral oil was used in ointments that were applied externally against such diseases as neuralgia (neurological disease), physical weakness, paralysis and tremor. Oil was also used for chest pains, coughing, asthma and rheumatism.

Three photos below: During World War II, Hitler was set on capturing Baku's oil fields to fuel his own efforts of the war. At that time Baku's oil was providing almost the entire supply of fuel for the Soviet resistance. Hitler's plan was to attck Baku on September 25, 1942. Anticipating the upcoming victory, his generals presented him a cake of the region - Baku and the Caspian Sea. Delighted, Hitler took the choice piece for himself - Baku. Fortunately, the attack never occurred and German forces were defeated before they could reach Baku. Photos from documentary film. The Allies were not unaware of Hitler's goals and had drawn up a map of the oil wells in Baku's city which they intended to bomb if Hitler managed to take Baku.

For example, the book "Jam-al-Baghdadi" (Baghdad Collection), written in 1311 by Azerbaijani author Yusif Khoyi, addresses the use of oil and bitumen in medicine. He said that ointments made from oil were applied externally to treat tumors, eye drops made of oil were used to treat cataracts, and eardrops were used to treat earaches.

![]() In his 1669 book "Tukhfat al-mu'minin" (Gift Of True Believers), Muhammad Mu'min recommended the use of oil-based remedies for asthma, chronic cough, colic, dyspepsia and intestinal worms.

In his 1669 book "Tukhfat al-mu'minin" (Gift Of True Believers), Muhammad Mu'min recommended the use of oil-based remedies for asthma, chronic cough, colic, dyspepsia and intestinal worms.

Similarly, 17th-century Azerbaijani author Hasan bin Riza Shirvani described the curative effects of "white oil", "blue oil", "black oil" and bitumen. Black oil is unrefined oil, "blue oil" is poorly distilled oil, and "white oil" is distilled oil or what Azerbaijanis today call kerosene - "agh neft" (white oil).

Oil was used for veterinary purposes as well. Abdurrashid Bakuvi, a 15th-century scientist who lived in Baku, wrote about oil's antiseptic properties. According to Bakuvi, residents of Baku and Absheron treated the coats of camels with oil to protect them from mange.

![]() In modern Azerbaijan, oil is still used medicinally, such as with Naftalan, a special oil that is found in its natural state in north-central Azerbaijan where a therapeutic center has been built. Several therapeutic centers in Baku also use oil as an alternative means of healing.

In modern Azerbaijan, oil is still used medicinally, such as with Naftalan, a special oil that is found in its natural state in north-central Azerbaijan where a therapeutic center has been built. Several therapeutic centers in Baku also use oil as an alternative means of healing.

Baku has not always been the architecturally beautiful city that it is today. In the 18th century, it was still just a small port on the Caspian Sea, with only 7,000 residents. Its architectural heritage included only the Shirvanshah Palace, the Maiden's Tower, the medieval city walls and several ancient mosques, bathhouses and fortresses. At that time, the amount of oil being extracted for commercial use was insignificant.

After Azerbaijan was occupied by Russia, oil extraction on the Absheron Peninsula increased substantially. Oil money was spent to construct beautiful houses and gardens in the city. By the second half of the 19th century, Baku had become the center of the Caucasus and one of the largest industrial centers of the Russian Empire.

Baku did not become such a large city overnight. By the end of the19th century, there were two large, beautiful cities in the Caucasus: Baku and Tiflis (now Tbilisi). These two cities competed with each other in magnificence and beauty. Shamakhi and Ganja (in Azerbaijan), Yerevan (Armenia), Batumi (Georgia) and other small cities were seen as less important.

At that time, the Russian government paid attention to Tiflis and spent a great deal of money beautifying the city. The Tsar's general-governors of the Caucasus made their seat of government there. Soon Tiflis was filled with beautiful buildings and considered to be the best city in the Caucasus.

Even though the Russian government did not pay nearly as much attention to Baku, the city developed through the use of its rich oil resources. During the period of 1890 to 1920, Baku surpassed Tiflis in both size and beauty. Oil barons such as Taghiyev, Naghiyev and Mukhtarov filled the city with palatial mansions in various European styles, including Baroque, Renaissance, Mauritanian and Early Modern.

The establishment of Soviet rule in 1920 meant the end of construction for the grand oil baron palaces. Instead, a number of standard "house-boxes" appeared throughout the city. But even throughout the Soviet period, Baku remained the largest, most important and most beautiful city in the Caucasus. In fact, during the Stalinist era, some very beautiful administrative buildings were constructed. One of the most impressive of these buildings, found on Nizami Street, was built for oil workers and named "Buzovnineft" (Buzovni Oil Field).

In terms of population, Baku was the largest city of the USSR after Moscow, St. Petersburg, Kiev and Tashkent. A number of oil processing plants, chemical enterprises and factories for oil drilling equipment were constructed there. Because of its natural resources, Baku became one of the most important industrial centers of the Soviet Union.

Ever since Azerbaijan gained its independence in late 1991 and began its transition to a market economy, oil has had even more of an influence on the city's architecture. As a direct result of the second Oil Boom, hundreds of new, beautiful buildings have already been built in Baku this past decade.

Oil and Culture

Baku's early-20th-century Oil Boom helped to revive many branches of Azerbaijani culture. Azerbaijani oil barons like Haji Zeynalabdin Taghiyev made huge contributions and supported the arts with their patronage. For instance, 110 years ago, Taghiyev financed the construction of the first European-style drama theater in the entire region. Several years later, he founded the Russian Muslim Alexandrian Female Boarding School in Baku, the world's first Muslim boarding school for girls.

Brilliant Azerbaijani composers like Uzeyir Hajibeyov and Muslim Magomayev were provided with resources and the opportunity to revolutionize Eastern music. Hajibeyov melded the Western musical genre of opera with the Eastern form of music known as "mugham" to create exquisite works such as "Leyli and Majnun" (1908) and "Koroghlu" (1937).

Oil turned Baku into a cultural center - not just of the Caucasus, but also of the entire Muslim East. Between 1900 and 1920, hundreds of Azeri-language newspapers, magazines and books were published in Baku. One of these was the famous "Molla Nasraddin" newsletter, founded by satirist Jalil Mammadguluzadeh and influential not only in Azerbaijan but also in Central Asia, Turkey, Iran and the Balkans.

Taghiyev and the other oil barons sent Azerbaijani students to study in Russia and Europe. This education abroad stimulated the intellectual growth of figures such as Mammad Amin Rasulzade, ideological leader of the Azerbaijan national movement and founder of the first Azerbaijani political party; Fatali Khan Khoyski, first President of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (1918-1920); Ahmad Aghayev, writer and ideologist of the Azerbaijani national movement; Jeyhun Hajibeyli, brother of composer Uzeyir Hajibeyov, member of the Musavat Party and one of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (ADR) diplomats (1918-1920) to France; and Sabir, a satiric poet who wrote about socio-political issues.

Consequently, it is no accident that the first democratic republic in the Muslim East appeared in Azerbaijan in 1918. Five years later, even while Azerbaijan was under Soviet rule, Azerbaijan became the first Muslim country to adopt a Latin-based alphabet to replace the Arabic script. Azerbaijani intellectuals Ahmad Aghayev and Ali Huseinzade deeply influenced the development of Pan-Turkist ideology in Turkey. And Muslims and Turks from all over Russia came to Baku to learn more about the Azerbaijani cultural heritage.

During the first Oil Boom, Azerbaijan deeply influenced the development of politics in Iran, especially in Southern Azerbaijan. Hundreds of peasants came to Baku to earn money in the oil fields. Baku residents called these workers "hamshahri" (compatriots). The peasants were so poor that they didn't even have regular clothes. Their shirts, arms and faces were always covered with black oil. Even today, Baku residents will say to someone with very shabby and dirty clothes: "Why are you dressed like a hamshahri?"

The "hamshahri" soon came under the influence of national Azerbaijani and socialist ideology. The ideas that they picked up in Northern Azerbaijan helped to promote the progressive movements in Southern Azerbaijan (Iran) under the leadership of Sattar-khan and Sheikh Mahammad Khiyabani in the early 20th century.

Cultural Center

During Soviet rule, Baku gained a reputation as a large cultural and tourist center. It was often the third major city (after Moscow and St. Petersburg) in the routes of many of the foreign diplomats, tourists, opera and pop singers who visited the former USSR. Of course, the fact that Baku could pay with hard currency from oil revenues, undoubtedly, influenced these visits as well.

Under the rule of the Communist Party, oil once again had a significant impact on Azerbaijani culture. Propagandists established the cult of the oil worker as a "hero of labor." Writers, painters and composers were commissioned to glorify "the great work of oil workers." Hundreds of songs, poems, novels and films were created about the life and work of these people.

For instance, Azerbaijani painter Tahir Salakhov, who now lives in Moscow and serves as chairman of the Russian Artist's Union, depicted scores of oil workers in paintings such as "Neft Dashlari"(Oil Rocks). Famous singer Rashid Behbudov performed songs about oil and played the main role in a musical film about oil workers, "On the Distant Shores," which was produced in the 1960s by Azerbaijan Film Studio. And poet Samad Vurghun wrote about oil in his famous poem "Azerbaijan".

Today, many international oil enterprises have helped to support various branches of Azerbaijani culture. Some oil companies provide financial help to orphanages, schools and kindergartens. Others restore architectural monuments, donate computers and technical equipment to Azerbaijani universities and scientific institutions or sponsor talented youth by funding their education at local and foreign universities.

Oil and Revolution

Up until 1917, the region known as Azerbaijan was ruled by the Russian Empire and its leaders were not very much involved with international politics. That situation changed with the Czarist regime's collapse and the ensuing October Revolution in Russia. The great Russian Empire, which had controlled Northern Azerbaijan for the previous 100 years, was overthrown. Azerbaijan and the other states in the Caucasus found themselves in a very confusing and precarious situation. Baku, with its large supply of oil, was the envy of many countries. Azerbaijan's large and powerful neighbors were envious of Baku and sought to gain control over it.

In 1918, Azerbaijan declared its independence, but the country's legitimate government was not able to enter Baku. As the center of the area's oil industry, the city remained in the hands of various foreign forces, including the Bolsheviks, the Central Caspian Dictatorship and the British.

In Soviet Russia, Lenin kept a watchful eye on the rich oil fields of Baku and dreamt of gaining control of them. "Soviet Russia can't survive without Baku oil." Lenin said repeatedly. "We must assist the Baku workers in overthrowing the capitalists so they can join Russia again!"

The Russian Bolsheviks worked to recapture the power. They supported the 26 Baku Commissars, who were mostly Armenian and Russian, not Azerbaijani. The Chairman of the Baku Commune of Commissars, Stepan Shaumian, declared: "Russia suffers very much without Baku's oil. The international working class of Baku must help build the world's first Bolshevik state. We must supply them with oil. In turn, the Russians will send us bread and feed all of the poor in Baku!"

However, the Bolsheviks were not the owners of the Baku oil fields. To assist Russia, they first needed to capture the power structure of the city. But it was not so easy - most of the Azerbaijanis and even Russians in Baku did not want to live under the leadership of the Bolsheviks. As a result, the Bolsheviks used the Baku Armenians as their primary allies in the war for Baku oil.

Oil and Ethnic Conflict

Before the arrival of the Russian army in the early 19th century, Armenians and Azerbaijanis did not consider themselves to be enemies. In fact, these two cultures are very similar to one another, especially in terms of customs, music and cuisine.

So who or what provoked this animosity between Azerbaijanis and Armenians? In order to maintain its power and influence in the Caucasus and Asia Minor, Tsarist and Bolshevik Russia repeatedly attempted to arouse national hatred in the region. In 1918, the Bolsheviks encouraged Armenian Nationalists, known as "Dashnaks", to undertake pogroms against Azerbaijanis. The Dashnaks were members of the Armenian Nationalist Dashnaktsutsiun Leftist Party, which carried out military and terrorist actions.

That year, the Bolsheviks and Dashnaks conducted secret negotiations and decided to attack the Azerbaijanis in Baku and capture the city. The Dashnaks prepared themselves for a lengthy battle, stationing many armed troops in Baku. These fighters called themselves "Mauserists", referring to the large Mauser revolver that each of them carried. The Bolsheviks desperately needed Baku's oil and felt they couldn't wait any longer, so they urged the Mauserists to attack the Azerbaijanis.

In March 1918, the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict in Baku began. This outbreak was in reality a massacre of Azerbaijani civilians, not a war between military forces. Unlike Armenian Dashnaks, the Azerbaijanis in Baku had few weapons and military forces to protect themselves. They were not prepared to resist a strongly equipped enemy.

The Oil Barons anticipated the attacks as they had received warnings about the planned pogroms from informants and government authorities. They fled the city and hid in their countryside dachas, many to Mardakan on the Absheron peninsula. Some left for Moscow, St. Petersburg and Tehran. This left behind thousands of poor Azerbaijanis who didn't have country villas to escape to or enough money to leave the city. Many of the residents were not even aware that trouble was brewing.

Once the dust from the March 18th massacre cleared, an estimated 12,000 civilians had been murdered in their homes and in the streets of Baku. [Source: "Azerbaijan" newspaper - the official organ of Azerbaijan Democratic Republic government].

My great-grandfather, famous philanthropist Hatam Abdul Bagi (Generous Abdul Baghi, as he was called), was among them. In one incident, Armenian Dashnak commander Lalayan captured hundreds of Azerbaijanis and held them hostage in the Opera House, demanding heavy ransoms from their families. But after receiving the money, instead of releasing the victims as he had promised, he shot all of his hostages.

Another Dashnak leader, Amazasp, continued the pogroms throughout Baku and various cities in Azerbaijan. In Shamakhi, Dashnaks locked hundreds of people inside a mosque and set it on fire. In Guba and Salyan, Amazasp's forces killed and mutilated hundreds of civilians.

Even though few of them were armed, Azerbaijanis gathered in the streets to try to resist the Dashnaks. Famous flour and oil baron Agha Bala Guliyev went throughout Baku, declaring: "My compatriots! It is necessary to save our nation. I'll grant you 4,000 bags of flour from my factory. Come and defend our city!"

Likewise, oil baron Teymur Ashurbeyov told the Azerbaijanis: "I can offer you 4,000 guns and 200 boxes of bullets." Hundreds of Azerbaijanis went into the streets to defend their city from pogroms. However, the Armenian-Bolshevik coalition was stronger, and the Azerbaijanis were defeated.

In this way, the 26 Commissars captured the city. Baku oil was in the hands of the Bolsheviks. Stepan Shaumyan, the new head of the Baku government, said on the occasion: "I'm sorry that so many Muslim civilians died, but our victory is so great than we should not think about such insignificant things." Within one month, the Baku Commissars had sent 1.5 million tons of oil to Russia.

During the Soviet period, all of these terrible events were kept secret. Nobody could speak about the murder of thousands of civilians in various parts of Azerbaijan. Many people didn't even know that the remains of these victims had been buried in mass graves on the hillside of what is known today as Martyr's Alley. Only this year - 2002 - did the Azerbaijani Parliament identify these events and call them the "Genocide of the Azerbaijani People."

Oil Rescued Inner City

The only part of Baku left untouched by the Armenian-Bolshevik massacre was the ancient walled Inner City. This was largely due to the efforts of oil barons and local "gochus" (an outlaw-type character) who armed and mobilized the Azerbaijani resistance. Some of these oil barons bought weapons with their own money and distributed them among the population. Protected by the walls of the ancient fortress, the Azerbaijanis were able to stave off the Armenians, who were forced to retreat.

One of the most courageous resisters was Mammad Hanifa (1875-1920), who helped to organize the defense of the Inner City. The owner of the Volcano Steamship Company, he himself was the son of a famous oil baron and landowner, Haji Zeynaladin (1837-1915), nicknamed "Gatir" (Stubborn). Mammad Hanifa was engaged in the shipping of oil from Baku to Astrakhan, Rasht, Anzali and other ports in the Caspian. The oil business had made him very wealthy and influential in the Inner City. At this critical time, he used this oil money to save the Inner City from pogroms.

Mammad Hanifa's nickname was "Gochu Mammad Hanifa" (Brave Mammad Hanifa). His pastimes included wrestling and shooting his revolver. Before the Armenians attacked, his relatives cautioned him: "Soon, Armenians will kill all of the Muslims in the city. We are going to leave for our countryside homes. Don't be a fool, leave the city!"

But Mammad Hanifa countered: "I'm not a coward. The people in the Inner City consider me their leader. Besides, I'm the chief of the local Gochu. They respect and trust me. How can I run away and leave them alone in this terrible situation?"

Mammad Hanifa bought revolvers, guns and even machine guns and distributed them among the native residents. Then he conscripted all of the Inner City's men. Some of them were afraid of war and didn't want to defend the Inner City, but Mammad Hanifa made personal visits with his armed gochus and forced them to join him.

One story is told how a merchant named Abdul answered his pleas to join the resistance: "Please don't bother me! I have a large family. Who will take care of them if the Armenians kill me? I'm rich. Let me and my friends go home and pay you!"

Mammad Hanifa became enraged and replied: "I don't need your filthy money, you coward dog! I have a family, too, but I haven't shrugged from war. Stand up and come with me, or I'll kill you here on the spot!" The merchant joined.

Mammad Hanifa led the Inner City's defenders himself. His national hat, called a "papag", got shot through with bullets several times, but he himself was not harmed. This hat has been kept in my own family as a relic of these events: Mammad Hanifa was my grandmother's uncle.

In the end, the Inner City was saved, but Gochu Mammad Hanifa did not survive long afterwards. In 1920, he was arrested by Bolsheviks and assassinated as an "Enemy of the People."

I read these accounts about Mammad Hanifa's courageous efforts in the Azerbaijani newspapers of 1918 that documented these terrible events. No doubt, there were hundreds of other brave gochus throughout Baku who played an important role in saving civilians from the pogroms, but their efforts have been forgotten and obscured during the Soviet period (1920-1991).

Oil and International Politics

The Baku Commissars' power over the city did not last long. The Russian government took the Baku oil but did not want to send the bread in return as they had promised, so the poor in Baku starved. The Mensheviks and Dashnaks in Baku rose up against their former ally, Soviet Russia, and decided to invite the British army into the city. In the summer of 1918, a British military detachment was sent to Baku and arrested and shot the 26 Bolshevik Commissars. Again, Lenin was deprived of the Baku oil.

The Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (ADR) government, which was stationed in Ganja at the time, tried to return to Baku with some help from Turkey. On August 31, Turkish general Nuri Pasha entered Baku with just 3,000 soldiers and defeated the 30,000-man military coalition of Dashnaks and Russian Mensheviks. The English hastily retreated from the city, and the young Azerbaijani government was able to move its seat of power from the small city of Ganja to Baku. On November 17, according to an international pact, the Turks left Baku and the British army returned there again, formally recognizing the ADR government.

However, the Bolsheviks did not give up on their plans to seize the Baku oil. On April 18, 1920, the ADR was annexed by the 11th Red Army, and Azerbaijan became part of what eventually became the USSR. Moscow emissary Serebrovski was appointed to supervise the entire oil industry in Baku. After that, private owners were deprived of their oil resources and all their properties were seized and confiscated. This is the situation that continued for more than 70 years (1920-1991).

In 1920, many of the oil barons in Baku suspected that the ADR would be overrun by Bolsheviks, so they tried to sell the shares of their oil companies. Nobody wanted to buy them because the political situation in Caucasus was so volatile. One exception was the famous American millionaire John Rockefeller, founder of the Standard Oil Company. He dared to buy the oil shares from the Nobels, Mantashev, Naghiyev and other famous Baku oil barons. When Baku was recaptured by the Bolsheviks in 1920, Rockefeller was stunned. He was sure that the Bolshevik rule would be short-lived. He waited for them to be overthrown, but all in vain.

During World War II, Adolf Hitler went in hot pursuit of Baku's oil fields. At that time, 90 percent of all Soviet tanks and airplanes were powered by fuel from Baku. Hitler had drawn up plans to attack the capital on September 25, 1942. Documentary film footage even shows him, surrounded by his generals, celebrating what they thought would be an obvious win. The choice slice of the "Victory Cake", on which the word "Baku" was written, went to Hitler. The "Caspian Sea" was shared by others. Nor were the Allies oblivious to Hitler's obsession to lay claim on the Caspian; the British had even drawn up plans exactly where to target their bombs in Baku's "Black City" oil fields to destroy the oil fields if Hitler succeeded in taking the city.

Fortunately, the bitter winter of 1942 brought the stoic German troops to a halt in the isolated mountains of North Caucasus. Had Hitler succeeded in capturing Baku, the Soviet Army would have been deprived of its main source of fuel, and the war could well have ended differently. Not many people realize that they have Azerbaijan to thank for the significant role it played in helping the Allies defeat Nazi Germany.

After Azerbaijan became independent in 1991, once again the nation got the chance to benefit from its own oil resources. As of September 1994, nearly two dozen major oil contracts have been signed with international companies - some of the largest corporations in the world. As a result already millions of dollars have been invested in the local economy.

Life in modern Azerbaijan is still closely associated with oil. In addition to providing new jobs for Azerbaijanis, oil money has changed the architectural face of Baku. Hundreds of new buildings, markets, restaurants and gardens are being built throughout the city. Once again, Azerbaijan is turning out to be the economic and political center of the Caucasus and the driving force is, as it has been for centuries - oil.

Dr. Farid Alakbarov, a frequent contributor to Azerbaijan International, is chief scientific officer in the Department of Arabic Manuscripts at the Institute of Manuscripts. To read other articles by him, make a SEARCH here at AZER.com. Several of Farid Alakbarov's articles may also be found in Azeri Latin at AZERI.org - our website that features Azerbaijani language and literature.

azer.com/aiweb/categories/magazine/ai102_folder/102_articles/102_overview_alakbarov.html