How the Media Cracks Down on Critics of Israel

Nathan J. Robinson

I was fired as a newspaper columnist after I joked about U.S. military aid to Israel on social media.

t is widely recognized that critics of Israel, no matter how well-founded the criticism, are routinely punished by both public and private institutions for their speech. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) has documented a pattern by which “those who seek to protest, boycott, or otherwise criticize the Israeli government are being silenced,” a trend that “manifests on college campuses, in state contracts, and even in bills to change federal criminal law” and “suppress[es] the speech of people on only one side of the Israel-Palestine debate.” The Center for Constitutional Rights has shown that “Israel advocacy organizations, universities, government actors, and other institutions” have targeted pro-Palestinian activists with a number of tactics “including event cancellations, baseless legal complaints, administrative disciplinary actions, firings, and false and inflammatory accusations of terrorism and antisemitism” and concludes that there is a “Palestine exception to free speech.”

The effort to keep critics of Israel quiet sometimes takes the form of explicit government action—there is an open campaign to criminalize speech critical of Israel and some states even require oaths from government employees promising not to boycott Israel. But as Israeli journalist Gideon Levy notes in the Middle East Eye, it often comes in the form of baseless (and offensive) accusations that criticisms of Israel are definitionally anti-Semitic. In the United States, academic critics of Israel have had job offers rescinded or been otherwise kept from teaching, and CNN fired academic Marc Lamont Hill over his call for a free Palestine. In Britain, there has been a years-long absurd campaign to tar former Labour leader (and critic of Israeli government policy) Jeremy Corbyn as an anti-Semite. Human Rights Watch notes that the United States government has wielded unfounded accusations of anti-Semitism against it and against other human rights groups like Amnesty and Oxfam that have exposed Israel’s shoddy human rights record. Within Israel itself, the free speech rights of Palestinians are brutally suppressed, and even Jews supportive of Palestinian rights are regularly harassed by the state. Abeer Alnajjar of OpenDemocracy wrote last year about how “major, mainstream news media outlets are sensitized against any reference to Palestinian rights or international law, and any criticism of Israel or its policies.”

Personally, I had never thought about the question of whether I could suffer consequences for criticizing the government of Israel (and U.S. support for it). I have just about as much “free speech” as you can get in this world. Perhaps I should have thought about it more, though, because as soon as I crossed an invisible line, it was very quickly made clear to me. The moment I irritated defenders of Israel on social media, I was summarily fired from my job as a newspaper columnist.

I have been writing for the Guardian US since 2017, first as a contributor and then as a full columnist. I write almost exclusively about U.S. politics. I have never written about Israel. My editor has always been satisfied with my work, which is why I kept getting commissioned. I am good at putting out sharp, well-sourced, political commentary quickly, and needed little editing. (I only had a column spiked for content reasons once, as far as I can remember, which occurred when I criticized Joe Biden over Hunter Biden’s corrupt business ties.)

Here is the context of my firing. In late December, Congress was authorizing a new package of COVID relief money. At the same time, it was also signing off on $500 million more in military aid to Israel. Israel has long been one of the largest recipients of U.S. military aid, only surpassed in the last few years by Afghanistan (though not on a dollar-per-capita basis). It is, according to the Congressional Research Service, “the largest cumulative recipient of U.S. foreign assistance since World War II,” and U.S. aid makes up nearly 20 percent of Israel’s defense budget. Here’s a chart from 2015 republished by CNN:

It was depressing to see that at the same time Congress was giving the American people far too little COVID relief, it was also giving the most technologically advanced military on Earth more cruise missiles. (Defenders of the arrangement pointed out that technically the money for Israel to buy weapons was not part of the same bill as the COVID relief, it was part of an appropriations bill authorized simultaneously, which is a valid response to those who said that the money was “part of the COVID relief bill” but does not do anything to justify the spending.)

Personally I was appalled and depressed to see new funding for Israeli missiles being passed at the same time as pitifully small COVID relief. Israel is a nuclear-armed power (something they officially neither confirm nor deny but experts widely accept as true and Benjamin Netanyahu once accidentally admitted). It has almost complete dominance over the Palestinians. We have already given it so much military aid that it does not need. Why, during the pandemic, is Congress funneling money to new missile systems?

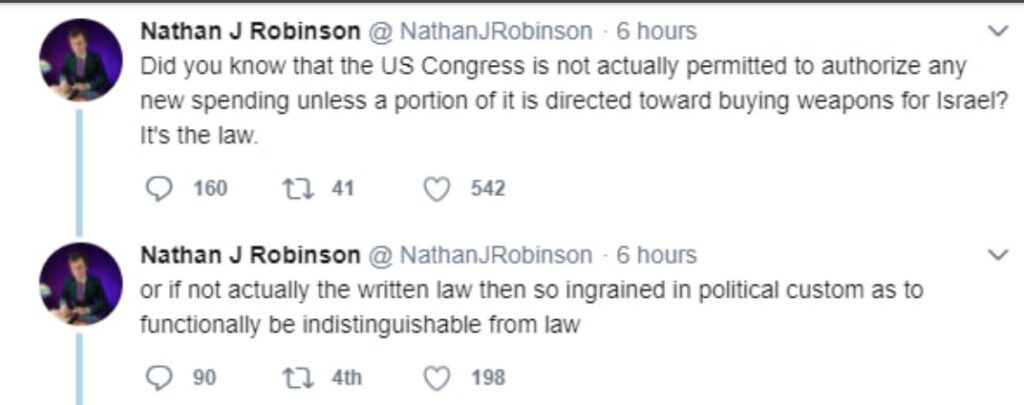

I am—to my constant shame—moderately active on Twitter, so I relieved my anger with a joke tweet. Sarcastically I wrote two linked tweets. (1) “Did you know that the US Congress is not actually allowed to authorize any new spending unless a portion of it is directed toward buying weapons for Israel? It’s the law.” (2) “or if not actually the written law then so ingrained in political custom as to functionally be indistinguishable from law.”* Of course, tweet 1 was sarcasm (which is common on Twitter), but to absolutely make sure that nobody thought this was some kind of actual law, I appended a second tweet to make it crystal clear that I was joking, this was 100 percent a joke, let there be no room for misinterpretation about this joke.

I don’t read my replies on Twitter, because they’re always just full of nastiness and I don’t like getting in arguments. But a colleague told me some people were calling me an “anti-Semite.” I laughed, because this was clearly absurd, the most cartoonish possible example of legitimate criticism being branded as bigotry. I was only pointing out the completely accurate fact that we give a huge amount of military aid to Israel, that we single it out for special support, even during a pandemic. (Nancy Pelosi once said that “If Washington D.C. crumbled to the ground, the last thing that would remain is our support for Israel,” and I believe her. Joe Biden once said that if there was no Israel, the United States “would have to invent an Israel” to protect our interests.) As the Congressional Research Service notes in a report, the U.S. has a straightforward commitment to a special relationship with Israel that will help it maintain a “qualitative military edge” over other countries. It is explicit U.S. government policy that Israel gets priority access to U.S. arms technology.

When you tweet, especially about something controversial, you can expect a few people to get mad and call you names. I didn’t have any idea how quickly I would be fired.

Later that day, I received an email from John Mulholland, editor in chief of the Guardian US. I had never received any correspondence from him before, since most of my Guardian communication is with the editor who deals with my work. (I’m not naming them, since they are a decent person and I do not want to jeopardize their own situation.) The subject line of Mulholland’s was “private and confidential.” I reprint it in full here:

Now, a few things should strike you here. First, the fact that Mulholland’s subject line is “private and confidential” means he does not want other people to know what he is saying to me. He would prefer that his words remain a secret. (He’d prefer it, but marking an email private is a request, not a binding legal obligation.)

Next, his argument that my tweet is “fake news” that could mislead people is clearly nonsense. Sarcasm, as I say, is common on Twitter, and on the off chance that somebody was so literal-minded as to believe I wasn’t joking in saying that all new spending required new military aid to Israel, I included an appended tweet making this very clear. There is no chance whatsoever that Mulholland would have sent me this email if the subject matter was not Israel. His problem was not that I used sarcasm. If I had said “In the U.S. it’s the law that Congress can only pass a spending bill if it contains a giant amount of frivolous waste (actually not the law but basically),” no reasonable person could think I would have heard from the editor in chief of the Guardian.

No, this was a pretext. The big problem was, as he says, that I was supposedly singling out the only Jewish state for criticism without noting the aid received by other countries. His email appears to quote (at the bottom) someone who called this anti-Semitism, though it is not clear who the quoted text is from.

What was clear from the email was that Mulholland was deeply pissed off. As I said, the charge is absurd—I didn’t single out Israel, U.S. policy did! I only pointed out that this is what we do, and that we do it intentionally, because we believe that Israel has a special entitlement to a “qualitative military advantage” that its neighbors do not. But I quickly saw that my job could be in peril. So I deleted the tweet and replied to Mulholland, apologizing for doing anything that could be construed as compromising the integrity of the paper. I need my income, and while it was deeply frustrating to me to have the Guardian policing my tweets, I grudgingly felt I would have to accept the new limits I expected would be imposed on my public speech. I knew that the censorship would be aggravating, but it seemed unavoidable and I hoped it would be limited. At-will employment means employers exert coercive powers over employees’ speech, even off the job, and I have to pay my rent like anybody else.

Mulholland replied to me, indicating that he appreciated my apology and suggesting that the incident could be put behind us. My editor texted me to ask me for information about the tweets, indicating the Guardian was displeased, but told me “don’t worry.” I took it to mean that as long as I kept my mouth shut about Israel on Twitter, the Guardian would keep publishing my columns on other subjects. A grubby compromise to be sure—perhaps one in retrospect I shouldn’t have even considered. It’s hard to justify keeping silent on the United States’ military support for a country abusing human rights just because one needs a paycheck, but writers who depend on writing income face difficult choices when the boss tells them which opinions they are allowed to have publicly. Still, in the moment, I maintained hope there was a way I could keep writing. I told myself I would do my best to speak my mind honestly without incurring editorial censure, though I worried about what this might entail.

But then a strange thing happened. Over the next few weeks, my editor became curiously non-responsive. I sent pitch after pitch for new columns. No reply. Or I’d get a promise that they’d speak with me soon, with no follow-up. It was very unusual, because for the past year, my editor had regularly called me asking for new column material. All of a sudden, radio silence.

Finally, on Monday the 8th, I got a call with my editor. They told me that they had wanted to publish my columns, but that the thing with Mulholland had made it impossible for the moment, and that they needed to have a talk with him to straighten things out. I, once again trying to be accommodating, said I knew there would be new guidelines I would have to abide by, and that I would happily sit down for a conversation with Mulholland to discuss his expectations.

Already, it was clear that I was explicitly being censored for sending a tweet critical of Israel. My editor made it clear that were it not for the tweet they would have accepted my pitches. Mulholland’s assurance that Guardian writers are “free” to speak their minds was clearly false. You’re free, but if you go after Israel, your pitches go in the wastebasket. My editor admitted as much to me directly, by saying that the denial of my pitches was the direct result of the tweet.

But it turned out that I was not just being temporarily ignored. On Tuesday, my editor called me and told me that after a conversation with Mulholland, it had been decided to discontinue my column altogether. I asked if it was possible for me to talk with Mulholland and work something out. My editor said it was not, and that Mulholland had indicated the paper would not work with me in the future either, meaning that I should not even bother to send occasional freelance pitches. (They did offer to pay me two articles’ worth of “kill fees” that would not cover a month’s rent.) There was no effort to offer any criticism of my performance; in fact, the editor indicated directly that my pitches would have been accepted if Mulholland had not been displeased with my tweet. It was made very, very clear to me: your tweet about Israel annoyed the editor in chief. Now you are fired. Do not come back.

* * *

Being fired from your job sucks, especially when it occurs without warning during the middle of a pandemic, when work is hard to find. I didn’t earn that much from my newspaper gig ($15,000 last year), but leftist political writing is not lucrative, and I needed that money. I had to be prepared to accept some policing of my social media by the Guardian in a desperate effort to keep my job. But there is no “three strikes” policy when it comes to criticism of Israel, no matter how justified the criticism, and no matter how far it falls from actual anti-Semitism. It did not matter that I swiftly deleted my words. You cross the line, you’re gone. This is not because of some vast conspiracy, but because of a policy by which an ally of the United States is considered to be above criticism (Saudi Arabia is often exempted from criticism as well.)

The Guardian is probably the most “progressive” mainstream newspaper in the United States, so we can tell a lot about the limits of speech about Israel from its actions. The paper is not right-wing, and it does publish criticisms of Israel, which it would surely point to as evidence of its commitment to open debate. I am not arguing that the Guardian never gives voice to critics of Israel or U.S. policy towards Israel, but that it wants to carefully screen its writers’ statements on the topic and make sure they only say what the paper’s editors have deemed appropriate.

Furthermore, it’s clear that the Guardian doesn’t want anybody to know that it will censor its writers’ social media posts on Israel. Mulholland did not want me to tell anyone what he was telling me. He wanted to emphasize that I was completely free to say what I wanted. Nobody gave me a set of guidelines for what I could and couldn’t say, because such a set of guidelines would be an explicit acknowledgment that writers are not free, that they have to toe a particular line on Israel, and only say what is editorially approved. I asked specifically for guidance as to what I could and could not say, but while the Guardian has in-house design and style guides, it does not have a formal speech code—just an unwritten one.

I’ve long been critical of those who paint a picture of the left as a group of totalitarian “cancel culture” warriors trying to stifle free speech. This picture has it exactly backwards. Reactionaries and bigots get huge megaphones, in general. Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) activists, on the other hand, operate under the threat of criminal prosecution. I am very firmly pro-free speech, for both principled and practical reasons, but I have critiqued some of the “pro-free speech” discourse that treats leftists as the primary threat, and doesn’t mention the way that critics of Israel can be fired for their speech. (The Harper’s letter on free and open debate, for instance, expresses admirable sentiments but seems more concerned about the threat of social justice than the threat to pro-Palestinian activists.)

The Guardian is under no obligation to employ me as a columnist, even though I am a very good columnist. As the editor of a magazine myself, I do not publish all viewpoints. We are selective. We exercise editorial judgment. That is our prerogative (although I don’t think I have ever criticized a writer for something they have tweeted on their own time, and I would offer writers maximum possible leeway with their tweets before ever considering having social media statements affect the writer’s employment with Current Affairs). I don’t think the New York Times was wrong to say that it didn’t want to publish op-eds calling for military crackdowns on dissidents. I don’t think a publishing house has to publish all books. If the Guardian’s position is that its opinion columnists can only have a very narrow range of opinions, or have to be carefully monitored for deviance, so be it. (The late anthropologist David Graeber, once a regular writer for the newspaper, refused to have anything to do with it during the last years of his life, saying that the Guardian used the presence of left-wing writers to give cover to its pushing of spurious anti-Semitism charges against Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party, and more than one critic has argued that the Guardian cynically wielded anti-Semitism to defend the centrist wing of the Labour Party against the left.)

But let the Guardian be honest about what it does and the ideological stances it demands of its writers. Let Guardian subscribers and readers understand that if the paper’s columnists get out of line, they will be fired, meaning that readers are not necessarily hearing the views they would hear if the paper didn’t exercise active control over columnists’ speech. My editor told me at one point that the paper considers columnists’ speech on social media an ongoing difficulty and is trying to figure out a way to deal with it. I assume this is indeed difficult, because the Guardian wants to maintain the right to fire people if they say the wrong thing, while also maintaining the pretense that they do no such thing, and keeping the discipline to “private and confidential” emails rather than putting it in a handbook.

I am in many ways fortunate. I have my own magazine where I can speak completely freely, accountable only to our subscribers. If I did not have a modest salary from elsewhere, losing this income would be even more devastating. I very much doubt that any other newspaper will hire me, considering that I have now been fired from one paper for supposed anti-Semitism. I must hope that Current Affairs continues to survive. This is not guaranteed. We are a small independent media institution funded solely by subscribers and small donors. The Guardian, on the other hand, is funded by a giant foundation with a £1 billion endowment.

I have noticed that a lot of people who are ostensibly pro-free speech have little to say when critics of Israel are met with professional consequences. Still my case is a relatively trivial one, and focus should remain on the Palestinians who have been massacred and maimed by Israeli military aggression (the lives of these Palestinians mean absolutely nothing to those who voice more outrage over my tweet than over the actual uses of the weapons systems we are buying Israel). The real problem with censoring critics of Israel is that it makes it easier for that country’s government to keep murdering protesters and maintaining a blockade that the United Nations says “deni[es] basic human rights in contravention of international law and amounts to collective punishment.” In 2018, hundreds of Palestinians including children and medics were shot by Israeli snipers at the Great March of Return protests—according to the Middle East Monitor, on “just one day, 14 May, the Israeli army shot and killed seven children” and over 1,000 demonstrators were shot with live ammunition—but Israel has never been held to account and the United States continued to supply it with arms.

I hope, however, that we can see exactly how the suppression of critics of Israel works. You say the wrong thing, you lose your position. No second chances. You will be tarred as an anti-Semite and your job will disappear overnight. This is one key reason why Israel continues to get away with horrific crimes. To speak honestly and frankly about the facts risks bringing swift censorship. Human rights violations continue with impunity. And when Israeli snipers target Palestinian children, the Guardian is complicit.

*I originally included my best recollection of the tweets since I had deleted them and did not have screenshots. I have since been sent screenshots of both tweets and have updated the article with the exact words.

https://www.currentaffairs.org/2021/02/how-the-media-cracks-down-on-critics-of-israel