U.S. POWER SUPPLY WILL BE IMPACTED BY WATER SHORTAGES

Richard Mills

Electricity enables our modern life style - the degree of dependency we have built into our lives in regards to “power on demand” has raised expectations that plentiful electricity will be available to us 24/7.

“Electrical power, in the short span of two centuries, has become an indispensible part of modern day life. Our work, leisure, healthcare, economy, and livelihood depend on a constant supply of electrical power. Even a temporary stoppage of power can lead to relative chaos, monetary setbacks, and possible loss of life. Our cities live on electricity and without the customary supply from the power grid, pandemonium would break loose.” Dieselserviceandsupply.com

According to a 2008 Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory study the most reliable state electrical power supply in the US is interrupted only 92 minutes a year, the worst is 214 minutes - these figures don't include power outages blamed on natural disasters.

Outages due to aging wires, pole transformers and other 1960s and 1970s infrastructure [1] pose the greatest threat. Since 1990 US power demand has risen 25 percent, yet spending on related infrastructure has climbed only seven percent.

The United States has the world’s most advanced economy, is the world's largest electricity consumer and rarely has sustained electricity shortages covering large areas.

Unfortunately that might soon not be the case - the United States is suffering through an extended heat wave and when combined with the worst drought [2] since 1956 energy production across most of the nation is threatened.

Power plants are completely dependent on water for cooling, they are overheating and utilities are shutting them down or running their plants at lower capacity.

If the water levels in the rivers they use for cooling drop too low, the power plant – already overworked from the heat – won't be able to draw in enough water and if the cooling water discharged from the plant raises already high river water temperatures above safe environmental limits a plant will be forced to shut down.

The lack of rain, and the incessant heat, has also increased the need for irrigation water for farming, meaning increasing competition between the agricultural and power generation sectors for the same water [3].

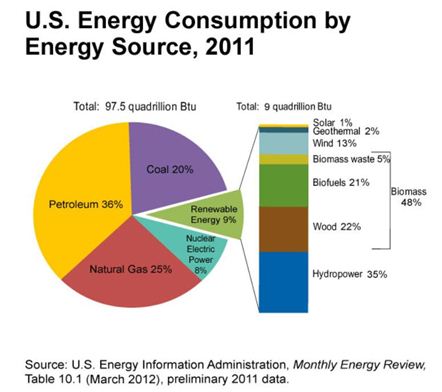

Burning Our Rivers: The Water Footprint of Electricity by River Network reports…

“For every gallon of residential water used in an average household, five times more is used to provide that home with electricity via hydropower turbines and fossil fuel power plants (40,000 gallons each month).

Electricity production by coal, nuclear and natural gas power plants is the fastest-growing use of freshwater in the U.S., accounting for more than about ½ of all fresh, surface water withdrawals from rivers and lakes. This is more than any other economic sector, including agriculture.”

Texas, with 25 million people, is the second most populous US state after California. An assessment projected total 2011 summer electricity demand would be roughly 64,964 megawatts (MW). An unprecedented heat wave drove demand to record levels - 68,294 MW. A blackout was avoided but operators used nearly all of their reserve generating capacity. As early as 2014 Texas is expected to have a 2,500 megawatt shortfall in generating capacity – that shortfall is equivalent to the output of five new, large power plants.

The average nuclear plant requires 2725 liters of water per megawatt hour for cooling, coal 1890 liters of water and natural gas plants 719 liters per megawatt hour.

Electricity Consumption Totaled Nearly 3,856 Billion Kilowatthours (kWh) in 2011. U.S. electricity use in 2011 was more than 13 times greater than electricity use in 1950.

Share of electricity use by major consuming sectors:

- Residential — 37%

- Commercial — 34%

- Industrial — 26% (includes "direct use")

- Transportation — Only a small percentage of electricity is used in the transportation sector, mostly for trains and plug-in electric cars

At the end of 2010 the total installed electricity generation capacity in the United States was 1,137.3 Gigawatts. North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) estimates that over the next decade 135 gigawatts of new capacity will be needed to meet the growth in consumption.

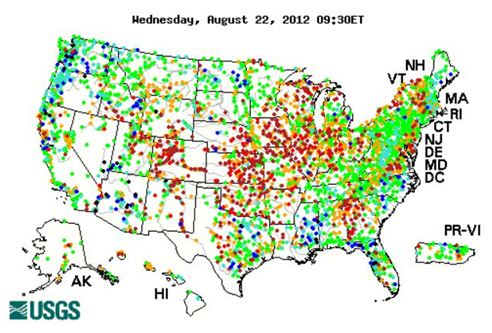

The colored dots on this map depict streamflow conditions as a percentile. Light green dots are flows classified in the 25th to 75th percentile, dark red are 10th to 24th percentile and bright red dots are classified as low.

We’ve used so much on the water in some of our river systems that nothing reaches the river's destination - no water reaches the mouth of the Colorado River, the Ococee River in the Southeastern United States has a large stretch of the river dry on certain days, Nebraska's Platte River is drying up and so is the not so mighty anymore Mississippi to name just a few of the many.

Rivers are the main source for inland electrical power plant cooling and many river levels are dangerously low, but what about water levels behind dams?

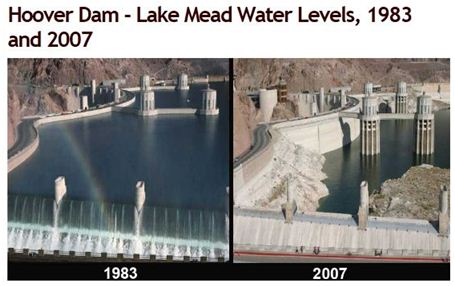

“We're teetering on the first shortage right now. How quickly [Lake] Mead goes down [is based on hydrology] probability. But the whole probability analysis, because of climate change, has been thrown out the window. We're experiencing anomaly after anomaly.” Pat Mulroy, General Manager, Southern Nevada Water Authority

2011

“Built on the Colorado River in Nevada during the Great Depression, the Hoover Dam was built to control floods, provide irrigation water and create hydroelectric power. The dam now provides electricity to 29 million Americans.

It has been a significant power generation source for decades, but it’s highly reliant on water and a 10-year dry spell has drained the water sources needed to operate the dam’s turbines at desired levels. The plummeting water levels have reduced the Hoover Dam’s power generation by 23 percent. This decrease in power generation at the Hoover Dam could cause electricity prices to increase five-fold for those in the Southwestern United States.

Lake Mead, created by Colorado River water impounded by the Hoover Dam, also displays warning signs – the dry spell has reduced the Lake’s water levels by 59 percent. Researchers at the University of California in San Diego predict that the lake has a 50 percent chance of decreasing to a point too low for power generation by 2017. They also predict that Lake Mead has a 50 percent chance of going dry by 2021.” Growingblue.com

Conclusion

Are more frequent droughts, long heat waves and an increasing population [4] going to continue to strain power generation in the future? Climate change, dropping surface water levels, an aging power transmission grid and power shortages should be on everyone’s radar screen. Are they on yours?

If not, maybe they should be.